The Standardization of Law and Its Effect on Developing Economies Katharina Pistor

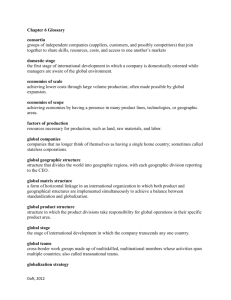

advertisement