State Taxation and the Reallocation of Business Activity: Xavier Giroud Joshua Rauh

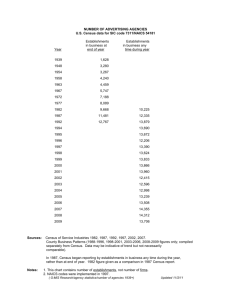

advertisement