by 1985 Sebastian Gray Architect

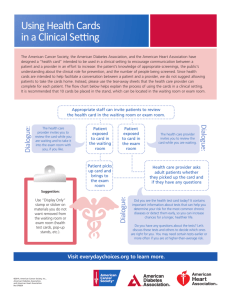

advertisement