Document 10618201

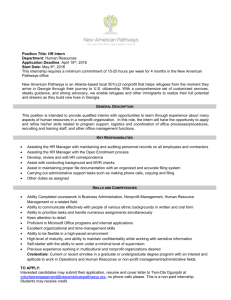

advertisement