Understanding Osteoporosis Learning Objectives

advertisement

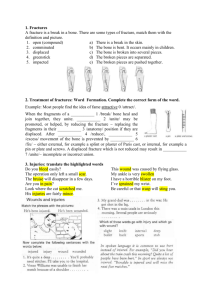

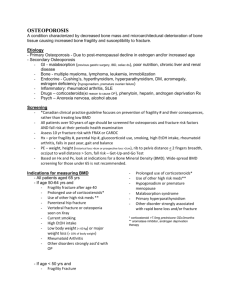

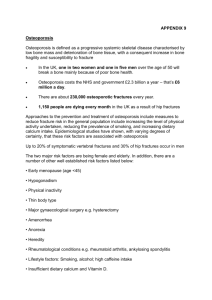

Understanding Osteoporosis Jeri W. Nieves, PhD Associate Professor of Clinical Epidemiology Columbia University Director, Bone Density Testing Helen Hayes Hospital Everyone has a Role to Play in Improving Bone Health This report is a starting point for national action Learning Objectives • Understand the public health impact of osteoporosis • Describe methods to identify the risk and the importance of fracture reduction • Describe the treatments for fracture reduction currently available. NYSOPEP The New York State Osteoporosis Prevention and Education Program Definition of Osteoporosis A skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength predisposing a person to an increased risk of fracture. Bone strength primarily reflects the integration of bone quality and bone density. Established in 1997 Evidence-based education 6 regional centers Visit the website www.NYSOPEP.org Bone is alive! National Institutes of Health (USA) Consensus Statement on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy, 2000 There is a cycle of breaking down and rebuilding bone called Normal Bone Osteoporosis bone remodeling 1 Osteoporosis: A Growing Concern for Health Plans Osteoporosis • 44 million people have osteopenia or osteoporosis1 − 34 million people have osteopenia or low bone density − 10 million people have osteoporosis • Osteoporotic fractures are more common than heart attack, stroke, and breast cancer combined2-4 1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004. 2 Riggs BL, et al. Bone. 1995;17(5)(Suppl.):505S-511S. . 3 American Heart Association. Heart and Stroke Facts:1996 Statistical Supplement. 4 Cancer Facts & Figure: 1996. American Cancer Society. • Baby boomers and now at risk • Osteoporosis is under-diagnosed • Osteoporosis is under-treated “…Fractures…are “…Fractures…are by far the most important consequence of poor bone health since they can result in disability, diminished function, loss of independence, and premature death.”* *U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library. Fragility Fracture Rates in a Managed Care Population 60% $60 Fracture Cost $50 40% $40 30% $30 20% $20 10% $10 0% Wrist Leg Arm Hip Pelvis Clavicle Millions of Dollars Percent of Fractures 50% Vertebral Adachi J, et al. Online publication of abstract presented at: Annual Meeting of the European Calcified Tissue Society. The Osteoporosis Continuum Spine Fractures May Cause: Pain Loss of height Stooped posture Difficulty breathing Healthy spine Kyphotic spine 50 Menopausal 55+ Postmenopausal 75+ Kyphotic Experiencing vasomotor symptoms At greater risk for vertebral fracture than any other type of fracture At risk for hip fracture and vertebral fracture Stomach pains/digestive discomfort Loss of selfself-esteem Increased risk for spine and other nonnonspine fractures (including hip fracture) 2 Hip Fractures have Serious Consequences Only 1 in 10 return to full activity 1 in 5 need a skilled nursing facility within a year 1 in 4 become disabled Many become isolated and depressed 1 in 5 die within a year of the fracture Promoting Bone Health Follow a bonebone-healthy diet WellWell-balanced, adequate calcium & vitamin D Engage in regular physical activity Avoid harmful behaviors Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption Assessing for and treating secondary causes Certain Diseases/Conditions Diseases that cause poor intestinal absorption (Crohn’s (Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, liver disease) Diseases associated with immobility or bed rest for more than 6 months (stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis) It is important to identify people at risk in order to prevent fracture • Risk factor identification • Bone density testing • Prior fracture It is never too early or too late to prevent fractures Risk Factors That Individuals Cannot Change Family history of osteoporosis and/or fracture Older age Being female Ethnicity (esp. Caucasian, Asian or Hispanic) Menopause at an early age Certain medications and/or medical conditions that may lead to bone loss or increase the risk for osteoporosis Certain Medications Steroid medications used for more than 3 months (Cortisone, Prednisone) Excess thyroid hormone replacement Antiseizure medications (Dilantin (Dilantin or phenytonin, phenytonin, Depakote) Depakote) Some cancer treatments 3 Risk Factors That Individuals Can Change Low lifetime calcium and/or vitamin D intake Lifetime lack of exercise Tobacco use Excessive alcohol use Being underweight Hormonal imbalance Vitamin D and Falls Based on a review of 5 studies, if we treat 15 people over the age of 65 with Vitamin D supplementation (~800 IU) we will prevent one fall. Secondary Prevention Activities that block the progression of osteoporosis to a fracture Early detection of those at risk Prevent the disability from the disease by treatment of those at sufficient risk Vitamin D, Calcium and Fractures • Four studies in elderly patients have found that supplementation with both calcium and vitamin D, resulted in fracture reductions (2443% in hip and 22-54% in all non-spine fracture). In WHI, compliant women had a 29% reduction in hip fracture. • One study of vitamin D alone found that there was no effect on fracture, although less than half the people took the vitamin D • There was a 22% reductions in fracture after 100,000 IU vitamin D were given every 4 months for two years. Exercise has the potential to: Increase bone density in youth and young adulthood Maintain and may modestly increase bone density in adulthood Prevent and minimize kyphosis Increase muscle mass Improve balance and agility Reduce the risk for fallfall-related fractures Bone Mineral Density Tests Requires a prescription with a diagnosis Dual X-ray Absorptiometry Gold standard: hip and spine Painless, noninvasive Safe: low dose xx-ray Can determine mineral content of bone 4 Who Should get a BMD test? Using T-scores to Define Bone Health All women by the age of 65 All men by the age of 70 Postmenopausal women or men who have clinical risk factors Adulthood fractures, kyphosis, kyphosis, family history Chronic diseases that increase risk of osteoporosis Medications that increase risk Active or recent smoking Being very thin The Future of BMD Testing Osteoporosis Low Bone Mass (- 2.5 and lower) Normal Bone Mass (Between -1.0 and - 2.5) ( -1.0 and above) ......- 3.5 … - 3.0 … - 2.5 … -2.4 … -2.0 … -1.5 ……-1.1... -1.0…0.0 …+1.5 …+2.0... Ten-Year Risk of Hip Fracture by BMD and the Number of Risk Factors •The move to absolute risk 35.0 •Absolute risk: Defines the risk of an event specifically for that person over a reasonable time. 17.9 23.4 30 5.6 10.5 20 10.6 10 >2 2.7 5.8 2 1- 1.4 0 0 ≤ -2.5 -2.5-<-1.0 ≥ -1.0 Total hip BMD t score be r fa ct of r or is k s •4 times what and over what time? 40 N um •Relative Risk: Ms Smith had a bone density evaluation. Her T-score is -2 which increases her risk of fracture by 4 times. 10-year risk of hip fracture (%) Diagnosis Based on Bone Density Test Taylor et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1479. Clinical Risk Factors1 Identifying High-Risk Patients Combination of BMD and risk factors leads to improved risk identification BMD: Identifies patients with bone loss Input of additional quantifiable risk factors identifies patients at risk for fracture in conjunction with BMD LowerLower-efficiency detection of fracture risk HigherHigher-efficiency detection • • • • • • • • • Age Weight or BMI Femoral neck T-score* Previous low trauma fracture after age 50 Current cigarette smoking Secondary osteoporosis (e.g. RA) High alcohol intake (> 2 units/day)** Family history of hip fracture (M or F) Prior or current glucocorticoid use 1. WHO Report. 2007. In production. Subject to change upon release of finalized WHO Report. 5 When is Medication Needed? SHOULD TREAT people with: prior clinical vertebral or hip fracture prevalent vertebral deformity BMD in the osteoporosis range (T(T- score < -2.5) Antiresorptive medicationsmedications- reduce bone loss Bisphosphonates: Bisphosphonates: MAY TREAT people with BMD TT-scores between –1.5 and –2.5 depending on number and severity of risk factors: U.S. FDA-Approved Medications for Osteoporosis prior adulthood fracture (non(non-spine, nonnon-hip) older age family history of fracture low body weight high bone turnover medications/diseases smokers alendronate sodium (Fosamax (Fosamax)) or (Fosamax (Fosamax Plus D) ibandronate sodium (Boniva (Boniva)) risedronate sodium (Actonel (Actonel)) or Actonel and Calcium 1 0.8 34% 0.6 • 0.4 There was a 34% reduction in clinical vertebral fracture and 0.2 0 n=62 Placebo (N=8102) n=44 HRT (N=8506) WHI: Risk-Benefit Assessment 60 RH=0.66 (95% CI=0.450.98) • No. of cases per year in 10,000 women % of Women With Hip Fracture Over 5.2 Years WHI HRT Study: Incidence of Fractures estrogen therapy (ET) or hormone therapy (HT) raloxifene hydrochloride (Evista (Evista)) salmon calcitonin (Miacalcin) Miacalcin) Anabolic agentsagents- build bone teriparatide or parathyroid hormone (Forteo (Forteo)) Risks Neutral Benefits Endometrial Deaths cancer Colorectal Hip cancer fractures 50 40 30 20 10 0 24% overall reduction in fracture occurrence Heart attacks Strokes Breast cancer Blood clots Placebo Estrogen + progestin DSMB = data and safety monitoring board. Adapted from: Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333. Women’s Health Initiative. At: http://www.whi.org/updates/update_hrt2002.php. Accessed January 2006. WHI: Risk-Benefit Assessment No. of cases per year in 10,000 women 90 80 Risks Neutral Uncertain* Benefits 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Strokes Deaths Colorectal cancer Placebo Heart attacks Blood clots Breast cancer Hip fractures Estrogen Women’s Health Initiative. At: http://www.whi.org/updates/update_hrt2004.php. Jan 2006. 6 Percent of Patients with Incident Nonvertebral Fractures Effect of Raloxifene on Nonvertebral and Hip Fracture Nonvertebral Fractures A hormone usually administered by nasal spray approved for osteoporosis treatment in women five or more years after menopause Hip Fractures 15 Benefits 3 Placebo 10 2 Raloxifene Pooled 5 Raloxifene Pooled 1 Placebo 0 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 Months Calcitonin (Miacalcin) Miacalcin) 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 Months 9 Prevents bone loss in the spine but least potent of all the medicines 9 Reduces risk of spine fracture in the older woman (less than other medications) 9 No proof that it reduces fractures anywhere else 9 May have pain relief properties following spine fracture Possible Side Effects 9 Runny nose, nose bleeds, nose pain Ettinger B. JAMA. 1999;282:637-645. Fracture Risk Reduction in Ibandronate Trials Bisphosphonates Approved for Treating Postmenopausal Osteoporosis FOSAMAX PLUS D™ Actonel Boniva (alendronate sodium/ (risedronate sodium tablets) (ibandronate sodium) tablets or injection cholecalciferol) Tablets and INDICATION INDICATION • Increases BMD • Increases BMD INDICATION • Reduces incidence of vertebral fracture and a composite end point of nonvertebral fracture • Increases BMD • Reduces incidence of hip and spine fractures New and worsening vertebral fractures –52% –52% Clinical (symptomatic) vertebral fractures –20 –40 DOSING DOSING DOSING FOSAMAX PLUS D 5 mg/day or 35 mg once weekly Actonel with calcium 2.5 mg/day or 70 mg/2800 IU once weekly FOSAMAX –60 Injection 3 mg every 3 months administered over 15-30 seconds ADMINISTRATION ADMINISTRATION ADMINISTRATION Take at least 30 min before first food of the day. Do not lie down for at least 30 min after dosing. Take at least 30 min before first food of the day. Do not lie down for at least 30 min after dosing. Take at least 60 min before first food of the day. Do not lie down for at least 60 min after dosing. Clinical Osteoporotic Nonvertebral Fractures vs Placebo in Ibandronate Trials P = 0.0003 Absolute Risk Reduction –49% Year 3 P value unreported Year 3 150 mg once monthly 35 mg and 500 mg calcium 70 mg once weekly or 10 mg/day 4.9% 5.3% Year 3 P value unreported 2.5% Boniva (ibandronate sodium) Tablets, Full Prescribing Information (NDA21-455). http://www.rocheusa.com/products/Boniva/PI.pdf. Accessed on March 31, 2005 Risedronate: Cumulative New Vertebral Fracture Incidence With Prior VFx 10 9.1% 8.2% 8.9% Control Risedronate 5.0 mg 20 8 6 15 Patients (%) Rate of Nonvertebral Fractures, % 0 • Reduces incidence of vertebral fracture New vertebral fractures % Relative Risk FOSAMAX®(alendronate sodium) Tablets With Prior VFx 4 2 0 Placebo (n = 975) Daily Ibandronate (n = 977) Intermittent Ibandronate (n = 977) 10 # 5 # # 0 0 Chesnut CH III et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1241─1249. Risedronate reduced vertebral fracture risk by 41% at 3 years, p = 0.003 12 24 36 Month #p < 0.05 vs. control Harris, et al. JAMA. 1999 7 Alendronate: Vertebral Fracture Arm of FIT Risedronate: Hip Fracture Data 4 3 No Effect Observed 2 1 0 PBO 5 4 3 2 1 0 RIS 5 mg 40% Reduction at Year 3 P=0.009 PBO RIS 5 4 1050 47% Reduction (P=0.001) 15% Placebo Alendronate 10mg n=981 n=965 Any New Vertebral Fractures 3 2 PBO Hip Fractures FIT VFA1 FIT VFA1 2.3% 1.2% –47% Year 3 P<0.001 7.1% –51% Year 3 P = 0.047 Risk Reduction Relative: 53% Absolute: 2.9% 1 Relative: 65% Absolute: 9.3% 50 40 30 20 10 0 64 22 Placebo FORTEO (n=448) (n=444) 15 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 14 Placebo FORTEO (n=544) (n=541) defined as occurring with minimal trauma MicroCT Images of Transiliac Crest Biopsy Before and After Teriparatide 6 4 3 30 Risk Reduction 60 5 2 0 (RR 0.35, 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.55) (AR: Placebo 14.3%; FORTEO 5.0%, P <0.001) 1 0 % of Women Number of Women with Nonvertebral Fragility Fractures (RR 0.47, 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.88) (AR: Placebo 5.5%; FORTEO 2.6%, P <0.05) 20 15 10 5 2.3% Placebo Alendronate 10mg n=1002 n=1005 Neer RM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434-1441 FORTEO Reduces the Risk of Nonvertebral Fragility Fractures1 25 70 1.1% 1. Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB et al. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. 2. Data available on request from Merck & Co., Inc. Please specify DA-FOS73(4). 35 30 Number of Women with 1 or More New Vertebral Fractures % Relative Risk Absolute Risk Reduction –56% Year 4 P = 0.044 5.0% D.M., et al, Randomized trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures, The Lancet, Dec 7,1997; Vol#348: 1535-1541 With Prior VFx Vertebral Fractures –40 –48% 2- FORTEO Reduces the Risk of ≥1 New Vertebral Fractures 0 Year 4 P<0.001 55%Reduction (P=0.047) 4- 0 1Black –20 –60 0 % of Women FIT CFA2 (T-score <–2.0) (T-score <–2.5) 60.5% (n=1,313) Pooled Doses (n=2,573) Fracture Intervention Trials (FIT) FIT CFA2 4.9% RIS Fracture Risk Reduction in Alendronate Trials Hip Fractures Painful Vertrebral Fractures 2- Placebo Alendronate 10mg n=1002 n=1005 0 1. Actonel® [package insert]. Cincinnati, Ohio: Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals and Kansas City, Mo: Aventis Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2001. 2. McClung MR et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):333–340. Without Prior VFx 90% Reduction (P=0.047) 4- 1 (n=1,821) Pooled Doses (n=1,222) (n=1,220) (n=3,624) *The percentages are based on the number of women for whom vertebral-fracture status was known. Vertebral Fractures Multiple New Vertebral Fractures 8.0% Percent of Patients 5 20% Reduction Not Significant 15- Percent of Patients % of Patients With Hip Fracture % of Patients With Hip Fracture note: hip fracture (alone) was not a primary end point HIP (80+)2 With Prior VFx=45%* Age Range=80+ Percent of Patients HIP (70–79)2 With Prior VFx=39%* Hip T-score ≤–3.0 w/ risk factors or Hip T-score ≤–4.0 Age Range=70–79 With Prior VFx=87% Spine T-score ≤–2.0 Age Range=up to 80 % of Patients With Hip Fracture VERT (Combined)1 Reduction in Incidence of Vertebral Fracture1 Baseline After 21 months MicroCT images of iliac crest bone biopsies were obtained from a 65 year-old woman Jiang et al, J Bone Miner Res Neer RM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434-1441 8 Tertiary Prevention: Following a Fracture Block or slow the progression of disability It is important to prevent falls Physicians fail to diagnose and treat osteoporosis Bone density testing not performed Calcium and vitamin D supplements not given Effective medications not prescribed Therapy prescribed often does not conform Following a Fracture Calcium supplements reduce bone loss and fracture Vitamin D supplements reduce fractures and falls Physical activity preserves bone mass, builds muscle mass, reduces falls, delays loss of independence Bed rest reduces bone mass Medications reduce risk of future fractures Risk for Falls Fall Prevention One third people over age 65 fall each year; half fall more than once 1 in 10 falls results in serious injury 90% of hip fractures are the result of a fall Activities often decrease after a fall even if not hurt There are identifiable risk factors for falls Changes with aging Balance, coordination, strength, sensory, vision, blood pressure, circulation, cognition Use of medications Environmental factors More deconditioned and more likely to fall again Osteoporosis Treatment Rate After Fracture Decreases with Age as Fracture Incidence Rises Fall Prevention Targeted interventions: multiple risk factors Muscle strengthening/balance retraining Professional home hazard assessment and modification Stopping or reducing psychotropic medications 40 30 % Percent treated Women’s vertebral fracture incidence per 100,000 personperson-years 1,400 1,200 1,000 20 800 600 10 400 200 0 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 ≥90 Age 0 Melton LJ III et al. Osteoporos Int;10:214, 1999. Freedman KG et al. J Bone Joint Surg;82A:1063, 2000. 9 Steps to Healthy Bones Optimal nutrition Healthy body weight Yearly height checks Regular exercise Tobacco cessation Moderation of alcohol intake Fall prevention Medication when indicated Surgeon General’s Report “Federal, State, and local governments (including State and local health departments) to join forces with the private sector and community organizations in a coordinated, collaborative effort to promote bone health.” 10