Document 10607706

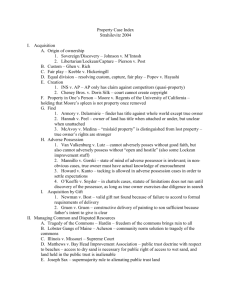

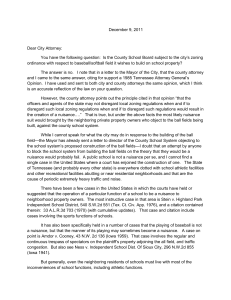

advertisement