by A Search for Dark Matter Annihilation

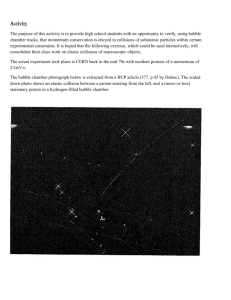

advertisement