Document 10603145

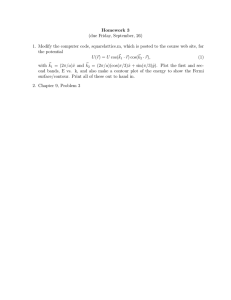

advertisement