Signature redacted 13 5 3 I

advertisement

A DIGITAL COMPUTER SOLUTION FOR LAMINAR FLOW

HEAT TRANSFER IN CIRCULAR TUBES

by

MAR 13

Perry Goldberg

53

L I rf R A-R

SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREES OF

BACHELOR OF SCIENCE AND MASTER OF SCIENCE

IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

February, 1958

Signature redacted

-

of the Author

Signature

~~0~~~~~~

Department of N9chanical Engir

C

'a.

Certified by

e ring, January 20,

1958

3ignature redacted

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by

..

Signature redacted

.a

e

l./Ga

a

S

n

Chairman, Departmental Commit7 e on Graduate Students

0,

A DIGITAL COMPUTER SOLUTION FOR LAMINAR

FLOW HEAT TRANSFER IN CIRCULAR TUBES

by

Perry Goldberg

Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering

on January 20, 1958, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Bachelor of Science and Master

of Science in Mechanical Engineering.

ABSTRACT

A need exists for determining solutions to the laminar flow heat transfer

problem for circular tubes in which the velocity and temperature profiles

are developing simultaneously. The equations describing the heat transfer

can be derived rather easily and must be solved using numerical or other

approximate techniques. Programs for the IBM 650 and 704 computers are

written to obtain heat transfer solutions using finite difference equations.

These programs and the solution methods are discussed in the present thesis.

Also presented in the thesis are numerical results obtained for various

Prandtl numbers and two different boundary conditions. The computer solutions are in agreement with the solutions calculated by W. M. Kays and

verified with experimental data.

Thesis Supervisor:

Title:

Warren M. Rohsenow

Professor of Mechanical Engineering

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is indebted to Professor W. M. Rohsenow, who supervised

the thesis, for his valuable comments, advice, and encouragement.

The

writer also wishes to thank Mr. B. Thurston of the MIT Computation

Center for his valuable assistance in running programs on the 704 electronic

data-processing machine.

This work was done in part at the MIT Computation Center,

Massachusetts.

Cambridge,

111

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

-Section

ABSTRACT . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .

i

. ..

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

LIST OF FIGURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

LIST OF TABLES

1.

INTRODUCTION

vii

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I

1. 1

Available Solutions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

1. 2

Derivation of Physical Equations . . . . . . . . . .

5

. . . . . . . .

8

. .

9

NUMERICAL METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

. . . . . . . . . . . .

12

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

2. 21

Langhaar Velocity Profiles . . . . . . . . . .

17

2. 22

Parabolic Velocity

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

. . . . . . . . .

21

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

. . . . . . .

24

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

24

1.4 Objectives of the Report

..

2. 1

Finite-Difference Equations

2. 2

Velocity Profiles

2. 3 Boundary Conditions

3.

v

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . .

1. 3 Boundary Conditions Considered . .

2.

. . .

..

. . ..

2.4

Local and Mean Nusselt Numbers

2. 5

Computing Machines

MECHANICS OF COMPUTER SOLUTIONS

3. 1

Logical Block Diagrams

. ...

3. 11

Velocity Block Diagrams

. . . . . . . . . . .

24

3. 12

Diagrams for 704 Solutions . . . . . . . . . .

25

3. 2

650 Program for Langhaar Velocity Profiles

. . .

29

3.3

704 Programs for Heat Transfer Solutions . . . . .

33

3.4

650 Test Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

iv

Page

Section

3. 5

4.

5.

704 Test Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

RESULTS OF STUDY......

39

... 42

...................

4. 1

Velocity Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

4. 2

Heat Transfer Results

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

4. 3

Discussion of Computer Results

. . . . . . . . . .

63

CONCLUSIONS.

....

-68

..............

. . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

APPENDIX A.

GLOSSARY

APPENDIX B.

LANGHAARtS VELOCITY PROFILES

APPENDIX C.

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . .. .

. . . . . . .

69

71

75

y

LIST OF FIGURES

F page No.

Caption

3

1

Available Constant Wall Temperature Solutions.....

2

Fluid and Surface Temperature Variations, Constant

4

Finite-Difference Approximation

5

Logical Block Diagram for Velocity Calculation

6

Block 00 for Velocity Calculation

. . . . . . . . . . .

7

Block 10 for Velocity Calculation

. . . . ..

8

Logical Block Diagram for 704 Solution . . . . . . . .

9

Block 00 for 704 Temperature Calculations

. . . . . . . . . . .

10

16

.

26

..

. .

. . . . . .

.

..

.

Temperature Difference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

Constant

27

.

Fluid and Surface Temperature Variations,

28

.

3

10

.

. . . . .

Wall Temperature

30

.

Fig. No.

31

Block 10 for 704 Mean Fluid Temperature Calculation

32

11

Generalized Velocity Profiles, Langhaar

45

12

Local Nusselt Numbers for Constant Wall Temperature,

Numerical Solutions

13

. . . . . . .

.

10

57

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...

Local Nusselt Numbers for Constant Temperature

Numerical Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Numerical Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Constant Wall Temperature Solutions,

Numbers

15a

59

Mean Nusselt

. . . . . . . .. . .

.. . .

..

.

14b

58

Mean Nusselt Numbers for Constant Wall Temperature,

.

14a

.

Difference and Langhaar Velocity Profiles,

60

Mean Nusselt Numbers for Constant Temperature

Difference and Langhaar Velocity Profiles, Numerical Solutions.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

vi

Fig. No.

15b

Page No.

Caption

Semi-Log Plot of Mean Nusselt Numbers for

16

.

Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

.

Constant Temperature Difference Numerical

66

Solutions for Parabolic Velocity Profiles and

Constant Wall Temperature . . . . . . . . . . .

vii

LIST OF TABLES

.

.

11

.

.

38

.

Numerical Solutions Presented in This Report for

.

40

.

1

Page No.

Caption

Table No.

.

41

5

Values of Langhaar Velocity Profiles Obtained on 650 .

42

6

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Wall

Langhaar Velocity Profiles . . . . . . . . . . . .

2

Comparison of 650 Computer Solution and Test

Solution for

3

Y =

2. 0

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Test Solution and Computer Solution for Pr

= 1. 0,

Langhaar Velocity Profiles, and Constant Wall

Temperature

4

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Kays' Solution and 704 Solution for Pr

= 0. 7,

.

.

Langhaar Velocity,

Pr = 1. 0 . . .

Langhaar Velocity, Pr

Langhaar Velocity,

49

= 2. 0 . . .

50

Pr = 5. 0 . . .

51

Langhaar Velocity,

Pr = 0. 5 . .

.

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Temperature Difference,

12

48

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Wall

Temperature,

11

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 0. 7 . . .

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Wall

Temperature,

10

47

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Wall

Temperature,

9

= 0. 5 . . .

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Wall

Temperature,

8

Pr

52

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Temperature Difference,

Langhaar Velocity,

Pr = 0. 7 . .

.

7

Langhaar Velocity,

.

Temperature,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

Temperature

.

Langhaar Velocity Profiles, and Constant Wall

53

viii

ture Difference,

55

Pr

Local Nusselt Numbers Parabolic Velocity,

= 5. 0 . .

.

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Tempera-

56

Different

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

L Increments

17

Pr = Z. 0 . .

.

Langhaar Velocity,

ture Difference, Langhaar Velocity,

16

54

Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Temperature Difference,

15

1. 0 . .

.

14

Langhaar Velocity, Pr

.

,Summary of Numerical Solutions Constant Tempera-

64

Mean Nusselt Numbers for Parabolic Velocity, Constant Wall Temperature,

A L

. . . . . .

...

and Varing Increments

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

13

Page No.

Caption

Table No.

65

1.

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of the gas -flow heat exchanger, the solution of the

laminar-flow heat transfer problem for low density fluids in small diameter

tubes received added importance.

this problem exists.

However,

At present, no closed form solution to

solutions have been obtained for a fluid

with Prandtl number equal to 0.7 *and

for very high and very low Prandtl

number fluids where the flow can be idealized as fully developed or uniThese solutions are limited in their usefulness because they were

form.

obtained for special cases.

Interest in the past was directed toward the solution of the problems

associated with oil-flow heat exchangers.

When oils are the primary

fluid satisfactory solutions have been obtained because oils are high Prandtl

number fluids; the velocity profile develops much faster than the temperature profile, hence the idealization of fully developed flow is adequate.

For heat exchangers utilizing liquid metals the idealization of uniform flow is adequate because liquid metals have low Prandtl numbers.

Therefore, the temperature profile developes much faster than the velocity

profile.

However, when fluids with intermediate Prandtl numbers are

used, no such flow idealizations yield an adequate discription of the velocity

distribution that exists within a circular tube.

-Hence, a more accurate

discription of the flow must be used along with numerical or approximate

techniques to obtain useful solutions.

1. 1.

Available Solutions.

The majority of available solutions have been obtained for constant

tube wall temperatures.

However,

this does not restrict the use of these

solutions because Klein and Tribus2 have demonstrated that by using

-*These numbers refer to references in Appendix C.

step functions the constant wall temperature solutions can be manipulated

to yield the solutions for any wall-temperature distribution.

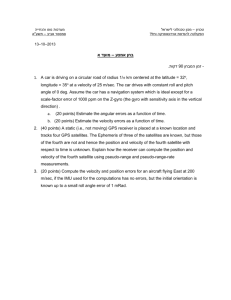

The available constant wall-temperature solutions are plotted in

Fig.

1.

The ordinate is the mean Nusselt number, the local Nusselt

numbers averaged over the tube length, and the abscissa is the inverse

of the independent nondimensional length variable that appears in the

energy equation, sometimes called the Graetz number.

All of these

solutions are based upon the idealization that the velocity and temperature

profiles are uniform at the tube entrance. , The following

is a list of the

available solutions that are plotted in Fig. 1:

1.

Two constant wall temperature solutions have been

proposed by Graetz, 3 one for uniform-velocity flow

and one for parabolic-velocity flow.

The uniform

velocity solution can be obtained for all Graetz

numbers.

However, the parabolic velocity solution

can be obtained only for Graetz number less than

100.

This solution involves an infinite series of

which only three terms are known.

For Graetz

numbers less than 100, the series converges rapidly

and three terms are sufficient.

But, for larger

Graetz numbers the convergence is slower and three

terms do not yield adequate results.

2.

Leveque3 developed a solution for parabolic-velocity

flow and high Graetz numbers by using a flat plate

solution as an asymptotic approximation.

This

solution is good only near the tube entrance, Graetz

numbers greater than 1000.

/00

-0*

80

60

-10

*10

GRAETZO

ELOCITY

-IivFORM

POHLHAU5EN

__

_

'EU

MODIFIED FOR

TUBE,

PPROXIMATION

-

PR= 0.7

-____

/0

__POHLH

AUSEN,

PLATE,

______FLAT

6

-

NORRIS AND STREID

-----

NTERPOLATION

NuMERICAL

LANGHAA

Pr=07-

-

--

-

20

BY WM.ifqy6,

VE LOCITY PROFILE, Pr= 0.7

SOLUTION

~

3

PARABOLIC VELOCITY

.20

.30 .40

.60

.so J.o

2.O

3.0

X/IL

FiG.I. AVAILABLE

W.0

I.0

aoi /o

20

Re Pr x /0-2

/

.10

CONVSTPSVT WALL T-EvPERATURE SOLUTIONS

30 40

60

S0

100

3.

Norris and Streid

have proposed that on a log log

plot, such as that in Fig. 1, a straight-line interpolation be made between the Graetz and Leveque

parabolic -velocity solutions.

4.

For any tube cross-section, when the velocity and

temperature are uniform at the tube entrance,

the

behavior near the entrance is approximated by the

laminar boundary layer on a flat plate.

Therefore,

at high Graetz numbers the Pohlhausen 3 flat plate

solution is a good approximation to the true solution.

For 0. 5

< Pr < 15 the Pohlhausen solution is

RePr

Nu

x/D

m

ln

(1)

4

4Nu.

1-mi

RePr

(x/D)

where the mean Nusselt number based on the initial

temperature difference Nu mi is

Nu

mi

0.664

Pr0 . 167

RePr 0.5

(x/D)J

The Pohlhausen flat plate approximation for circular

tubes can be improved by correcting the flow cross

Symbols are defined in Appendix A.

(2)

sectional area with the boundary layer displacement

thickness from the Blasius

3'

laminar boundary layer

solution.

5.

A numerical solution has been obtained by W. M. Kays

employing the Langhaar5 velocity profiles for a

fluid with Pr = 0. 7.

This solution obtained by

"hand". methods agrees well with experimental data.

A solution has been obtained by Sparrow using integral methods.

How-

ever, the accuracy of this solution is poor and, therefore, it is not plotted

in Fig. 1.

Solutions "2" and "4" are adequate for Graetz numbers

)

1000, but

inadequate for the real area of interest in heat exchanger design, Graetz

numbers 4 100.

All of the available solutions, with the exception of the

solution by Kays, are satisfactory only for very long or very short tubes

and for high or low Prandtl number fluids.

Therefore, to obtain adequate

design data in the laminar-flow region for gas-flow heat exchangers with

both temperature and velocity profiles approximately uniform at the tube

entrances,

a direct solution of the energy-balance differential equation

is necessary.

Numerical solutions of the energy equation for various Prandtl numbers

and for two different boundary conditions are presented in the present

report.

These solutions were obtained on a high speed digital computer

using numerical methods similar to those used to obtain the solution for

Pr= 0.7 byW.

1. 2.

M. Kays.

Derivation of Physical Equations.

When the only heat transfer mechanism in the tube is conduction,

when fluid properties are constant, and when conversion of mechanical to

thermal energy is neglected, the following differential equation is obtained

by applying the energy equation to an annular control surface in a space

bounded by cylindrical surfaces dx in length and of radii r and r + dr:

=Vc --+vrc -- (3)

kr -r ar rx Jr

+ k

r x2

4X

r

The terms to the left of the equal sign represent the radial and axial

conduction and the terms to the right represent the radial and axial

enthalpy flux.

This equation is reduced to

1 14

t

r Jr

r)

=

c

k

(4)

ax

or

.-Jr2

+

-r ar

k

(L)

2jx

if the following assumptions are made:

1.

The axial conduction terms are small compared

to the other transfer terms and can be neglected.

2.

The presence of the radial enthalpy term greatly

complicates the solution of the reduced equation

and because this term is small except at large

Graetz numbers the radial enthalpy flux can be

neglected without introducing very large errors.

The reduced equation, Eq. (5),

nondimensional variables

can be normalized by defining the

Ar

Tt 1

7 tI

V A

,

T

v

and

kx

LA

2

vmecr0

4(x/D)

RePr

Substituting, Eq. (5) becomes

.--.

++21-..-. JT

T

P2

R JR

V ...-TT

JL

(6)

An expression for the local Nusselt number Nu

is obtained by

equating the heat transfer rate per unit of length q as determined by the

difference between the wall temperature and the mean fluid temperature

with q as determined by the temperature gradient at the wall.

The

former expression for q is

q = hZlr0 At = hZrr0t

- Tm(7)

where h is the unit conductance for convective heat transfer.

The

latter expression for q is

= k21Tr

q = k2nr0 ~

r

wlr

wall

~~

0

JR

.

wall

(8)

The local Nusselt number is defined as

2hr 0

A hD

Nu

=.-.

Therefore,

by equating Eqs.

9

k

k

(7) and (8) and by solving for Nu

the

following result is obtained,

2

Nu

=

lJ R Iwall

(10)

TW - T m

The mean Nusselt number Nu

m

is the local Nusselt number

Hence,

averaged over the tube length.

L

Nu

Nu dL

=.

(11)

m L_0

After the temperature distribution T is determined at any cross

section L from Eq. (6), the mean fluid temperature is found by performing the following integration,

T

=2

VTRdR.

0

Finally, the local and mean Nusselt numbers are evaluated with

Eqs. (12) and (13).

1. 3.

Boundary Conditions Considered.

For the solution to the temperature equation the following two

boundary conditions are considered:

1.

Constant wall temperature.

2.

Constant wall-to-fluid temperature difference.

(12)

These two boundary conditions represent the extreems generally encountered in two-fluid heat exchangers.

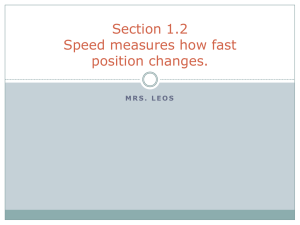

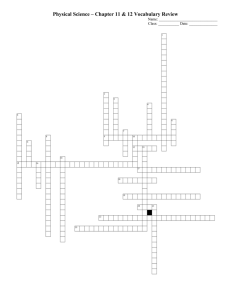

The fluid and surface temperature

variations for both conditions are plotted in Figs. 2 and 3, with L the

normalized length variable as the abcissa.

Figure 2 shows that for

Condition I the difference between the wall and the fluid temperatures

Figure 3

is large at the tube entrance, but decreases as L increases.

shows that for Condition 2, both the wall and fluid temperatures increase

as L increases, but that the difference between the two remains constant.

Condition 1 is a good approximation of the wall temperature distribution

that occurs in condensers, evaporators,

and often in parallel-flow heat

exchangers when the two fluid capacity rates and heat transfer resistances

are nearly equal.

For many fluid to fluid heat exchangers,

such as

counter-flow heat exchangers utilizing two fluids with equal capacity rates

and heat transfer resistances,

Condition 2 has application.

When either

boundary condition is used, the primary information of interest is the

mean Nusselt number.

With Nu m, the fluid exit temperature and the over-

all heat exchanger performance can be predicted.

Therefore, the local

Nusselt number is of secondary importance.

1'. 4.

Objectives of the Report.

The objectives of this report are:

1.

To present numerical solutions for laminar flow

heat transfer in circular tubes.

2.

To describe the digital computer solutions for

obtaining these solutions.

The numerical solutions should help simplify the trial-and-error

heat-exchanger design proceedure.

Table 1 is a summary of the numerical

solutions presented in this report for fluid flow described by the

Langhaar5 velocity profiles.

i0

5URFACE

K

i.e-

T

PLUID

I .6 -I

E

/,0

7.0

.1

0.z 0.3 .4

0.5

0.6

Q7

0.8

4CX/)

-

ReP

Fi.2.

FLUID

AND SURFACC

TEMP1RATURE

CONSTA/IT

V..A7AT/O1N.S

WAL-

T-MPERAT-iUqE

6

5-1

T

-LVI

4

/

35

0.0

0./

o.3

02

o.4

0.5 0.6

0.7

0.8

(xID)

4

Re P-

Fi&.3.

FLU/Da

/qND

SURFAC.E

TMPERATURE-

CONSTANr

VAR/A r/OM.1,

rEMPERqATURE

ThFFERG'SCE

TABLE 1.

NUMERICAL SOLUTIONS PRESENTED IN THIS

REPORT FOR LANGHAAR VELOCITY PROFILES

(Temperature and Velocity Assumed Uniform at Tube Entrance)

Prandtl Numbers

Boundary Condition

1

0.7

0.5

1.0

2.0

5.0

2

Solutions have been obtained also for fully developed flow (parabolic

velocity profiles) and these solutions are compared with the Graetz analytic

solution to help determine the accuracy of the numerical methods.

Solutions have been obtained for Pr = 10 and Pr = 50.

However, when

Pr = 10 or Pr = 50, the velocity profile developes much faster than the

temperature profile and the idealization of fully developed flow yields

adequate solutions for Graetz numbers 4

100.

Therefore, these solutions

are not included in the present report.

The following programs are discussed in the report:

1.

A program for the 650 magnetic drum data-processing

machine for calculating numerical values of the

Langhaar velocity profiles.

2.

A program for the 704 electronic data-processing

machine for obtaining the constant wall temperature

solutions.

3.

A 704 program for obtaining the constant temperature

difference solutions.

4.

A 704 program for determining the parabolic velocity

solutions.

2.

NUMERICAL METHODS

When the velocity distribution is other than a constant or some

simple function of R and L, the normalized temperature equation, Eq. (6),

is difficult to solve analytically.

Therefore,

alternate solution techniques

are a necessity when the fluid flow is described by the Langhaar velocity

profiles.

The proposed solution method discussed in the present section

involves approximating the continuous system with an "equivalent"

lumped-parameter system.

For this finite difference method of solution,

the basic approximation is obtained by replacing a continuous domain

with a pattern of discrete points within the domain.

Instead of obtaining

the continuous solution for T within the domain, approximations to T are

obtained only at the isolated points and when necessary,

values,

derivatives,

intermediate

and integrals are obtained from the discrete solution

by interpolation techniques.

The remainder of Sec. 2 presents (1) the finite difference approximations used to reduce the normalized temperature equation,

(2) the

resultant finite-difference equations for computing the temperature T,

(3) a discussion of the Langhaar and parabolic velocity profiles,

methods used to evaluate the mean fluid temperature,

number,

(4) the

the local Nusselt

and the mean Nusselt number, and finally (5) a brief discussion

of the computing machines used.

2. 1.

Finite -Difference Equations.

After the continuous formulation of the physical system is deter-

mined, the discrete formulation is obtained by replacing derivatives with

finite-difference approximations.

For the present study the following

commonly used approximations are utilized:

1

S T

=------TR-AR, L + TR+AR, L

JR

ZA R

= --

Equations (13),

-\

+ O AR

(TR-AR, L - 2TR,L+ T R+AR,L

JT

JT-

- 1 T R,L+AL - TRL

JL

AL

+

(13)

(A-)

+(ALI

(14)

(15)

\

(14), and (15) are termed explicit finite-difference

formulae because the only unknown appearing in the derivative expressions

is the desired quantity, in this instance TR, L+AL, for which the calculation is being performed and once the relationship between derivatives

is defined the unknown quantity can be obtained easily.

The derivative approximations are derived from Taylor series

expansions and the last term in Eqs. (13) through (15) expresses the

order of the Taylor series remainder.

When the intervals AR and AL

are small enough the remainder behaves essentially like a constant times

--2

-2

AR or AL.

/-/Hence, the terms 0 (ZAR

and 0 (AL

are indications

of the size of the approximation errors.

When Eqs. (13),

(14), and (15) are substituted into Eq. (6),

22T

.- -+.1.-. =1V._._. 2T (6) vl

R2

R J)R

L

the resultant expression can be solved for TR, L+AL to obtain the relationship

TR, L+AL

f1 TR+AR, L + f2 TR, L + f 3 TRR-AR, L.

(16)

14

The coefficients f , f 2 , and f 3 are defined as

A

L

iAR

2R

VJ1R

1

1

f

2

Z AL

-2

1

AR

and

-

f3

3

lil

V

AL

AR

I1

AIR

2R

An examination of the expressions for f 1 and f 3 indicates that as R goes

to zero the two coefficients and, hence, the centerline temperature go to

infinity.

in any real situation the centerline temperature can

However,

never go to infinity.

Eq. (16) cannot be used for finding the

Therefore,

centerline temperature T

Furthermore,

because the temperature

distribution is radially symmetric, when R is zero

TO+AR, L =

(17)

O-AR,L

Hence, to determine the centerline temperature f

and f3 can be added,

thus eliminating the 1/2R terms and yielding the equation

TO, L+AL

4 T AR, L +2

TO, L

(18)

where f 4 is defined as

)(ZAL)

V

AR

The finite-difference equations, Eqs. (16) and (18),

imply that when

the temperature and boundary conditions are known at the cross-section

115

AB of Fig. 4, the solution for all points within the shaded triangle ABC

How-

can be obtained if the velocity values are known within the triangle.

ever, the continuous system is parabolic6 and has a single characteristic

perpendicular to the tube walls across which discontinuities can occur.

Therefore, 'before the solution can be determined at points such as C in

Fig. 4, the boundary conditions at cross-section C must be known.

This

result indicates that implicit finite-difference formulae, which behave

more like the continuous system than explicit formulae, would yield more

accurate results than explicit finite-difference formulae.

the implicit formulae are used,

However, if

1/AR simultaneous equations must be

solved at each AL. - Therefore, this type of solution is more complex

than the explicit method and is much harder to handle on a digital computer.

The explicit formulae are used to solve Eq. (6) and the increment in AL

is chosen small enough such that the errors introduced by the finitedifference approximations are small.

The solution to the finite-difference equation, Eq. (16), will converge as long as all the coefficients f 1 , f.,

and f 3 are of the same sign.

Hence, the values for AL and AR cannot be chosen independently.

For

all solutions, the radius R is divided into 10 equal parts and AR is 0. 1.

Therefore, the limiting value of AL is chosen so that the coefficient f 2 is

positive throughout the calculation.

Because the smallest value of V used

in the calculation is 0. 384, the limiting value of AL is

AL

=0.0019.

(19)

For all but one of the solutions AL is less than AL

The solution for

Pr = 0. 5 is obtained by choosing AL greater than AL

and letting the

calculation proceed until f2 becomes negative,

at which time the

16

rse

WAWL

5~u

Fi G. 4.

FINITE -PDiFEREfcE

APPRoxlMATION

ac We A/L L

17

calculation is ended.

The convergence constraint was not violated for any

of the solutions presented in this report.

2. 2.

Velocity Profiles.

Numerical solutions for laminar-flow heat transfer in circular tubes

are obtained for two different velocity distributions, the Langhaar velocity

profiles and the parabolic velocity profiles.

The solutions for parabolic

velocity profiles are used to estimate the accuracy of the numerical

solutions obtained for the Langhaar velocity profiles.

2. 21.

Langhaar Velocity Profiles.

The equation proposed by Langhaar for the velocity distribution of

a laminar flowing fluid in a circular tube is

V(Y,

where the parameter

R)=

I('R)

-

(20)

is some function of a nondimensional length

variable (4 x/D)/Re that is independent of the Prandtl number,

(21)

\

Re

/

4 x/D

y. =4

The I's appearing in Eq. (20) are modified Bessel functions of the

first kind and are defined as

2k+ p

I (W)=

.

k=0

k!(k+p)!

Therefore, Eq. (20) can be rewritten

(22)

V(

(L

Z~)

Zk

(k!) 2

k= o

(k!

= -k= 0

)

,R)

$0

2k

00

(23)

r2

k=0

k! (k + 2)!

or removing the k=0 term from the summation and adding parens

R2

k=1I

V( 2, R) =

k! j

.

k

2

'2

(2

k-- I

. k!

(24)

2

(k + 2)(k + 1)

Equation (24) is in a convenient form to program for a digital computer.

The velocity V( 3, R) is calculated from this equation on a 650 magnetic

drum data-processing machine.

The two parameters that affect the nondimensional-velocity distribution are the tube radius R and the parameter (4x/D)/Re which

represents the length from the tube entrance to some cross section x.

The radius R was varied from its value at the tube center line to its

value at the tube wall in increments of 0. 1.

0

and

Therefore,

R .1

A R = 0. 1 for all solutions.

The length variable L of Eq. (6) and the parameter (4x/D)/Re are

related by the Prandtl number,

19

4x

L

I

Pr

(25)

D

Re

Hence, to make the values of V as calculated from Eq.

(24) directly

applicable to a finite-difference solution of Eq. (6) without interpolation,

the increment in (4x/D)/Re is chosen to be 0. 001, and for any Prandtl

number the increment

. 001/Pr.

AL for a finite-difference solution is chosen as

Also. Langhaar's data indicates that the velocity profile is

fully developed at (4x/D)/Re equal to 0. 300.

Therefore

when the

stability conditions discussed in Sec. 2. 1 permit, the solutions are

calculated for values of (4x/D)/Re less than or equal to 0. 250, at which

point the temperature profile is sufficiently developed such that interpolation to the fully developed temperature solution yields adequate

results.

The actual values of J used on the digital computer are obtained

by first plotting the values tabulated in Langhaar's paper 5 then

selecting values of

'

for

(4x

0 .

=

0. 250

Re

at increments of (4x/D)/Re equal to 0.001.

2. 22.

Parabolic Velocity.

When the flow in a circular tube is fully developed the velocity

profile is parabolic and constant at each cross section.

The velocity

is a function of radius only

V = 2(1 - R )

(26)

and the coefficients fl, f 2 ' f 3 , and f4 can be expressed in terms of R,

and

AL.

By substituting Eq.

(26) for V in the definitions of fy

f'

A R,

f3'

and f 4 the coefficients for fully developed flow are obtained;

f

11

(29)

AL (

1

,.

AR

A--R2

2. 3.

Z7

R2)

AL

2A L

.

2R

1(28)

--

AR

f

R2

2 AL

1

f

(Z(l

1

2(1 - R2

A R

2R

(30)

1

2(l - R2

Boundary Conditions.

The numerical solutions presented in this report are obtained

assuming the velocity and temperature constant at the tube entrance.

The

nondimensional fluid temperature at the entrance is assumed always to be

one and for the constant wall temperature solutions the wall temperature

is assumed to be two.

For the constant temperature difference solutions

the difference between the wall temperature and the mean fluid temperature

is taken as one along the length of the tube.

When computing the constant

temperature difference solutions the wall temperature at any cross section

is obtained by adding one to the mean fluid temperature at that particular

cross section.

Z. 4.

Local and Mean Nusselt Numbers.

Once the temperature distribution is obtained at some cross-section L,

the local Nusselt number Nu

is determined from Eq. (10).

However, before

this calculation can proceed the mean fluid temperature and the temperature

The mean fluid temperature is

gradient at the wall must be evaluated.

R

T

But, R

is one.

m

=

R

max

2

(31)

RVTdR.

0

max

Hence,

Tm = 2

(32)

RVTdR.

0

The integral in Eq.

(32) is evaluated with Simpson's rule.

The resultant

approximation to the mean fluid temperature is

R= 0. 9

Tm = ZAR

m

R=0. 1

[(RVT)R- AR + 4 (RVT)R + (RVT)R+ AR1,

ARRR1R

(33)

R = 0. 1, 0. 1 + 2 AR, 0. 1.+ 4 AR, -.. 0.9,

where the subscripts refer to the radius at which the values of R, V, and T

are obtained to form the product (RVT).

To determine the mean fluid

temperature at any cross section L, the wall temperature at L is not needed

because the velocity is zero at the wall and, therefore, the term (RVT)R+

AR

is always zero when R = 0. 9.

Hence, for the constant temperature difference

solutions the mean fluid temperature is obtained at section L although the

wall temperature at L is unknown.

To evaluate the temperature gradient at the wall, the temperature

profile at any cross section L is approximated as the parabola

T =Twall + a(1

-

R) + b(

-

R)

(34)

and the gradient is obtained by first differentiating Eq. (34) with respect

to R, then letting R equal one.

The gradient is

(R

= - a.

(35)

R=

The constant a is found by evaluating Eq. (34) at two different radii,

R = 0. 9 and R = 0. 8, and solving the two resultant equations for a in

terms of T o8,'

T 0.9, and Twall;

a = 5 (4T 0 . 9 - T 0 . - 3 Twall)

8

(36)

and the gradient at the wall is

T

(R/R=I

With Eqs. (10),

= - 5(4T 0 .9

- T0.

8

- 3 Twall).

(37)

(33), and (37) the local Nusselt number at any

section L can be determined when the temperature profile at L is known.

The mean Nusselt number given by Eq. (11)

L

Nu

mL

is evaluated also with Simpson's rule.

Nu dL

J

X

Hence, Num is approximated as

(11)

L- A L

Nu

AL

m

(Nu

L- AL

3

+ 4Nu + Nu+

),

L+ AL)

L

(38)

A L

L =

A L,

3 AL, 5 AL,

L - A L,

where the quantities being summed are local Nusselt numbers evaluated

at the cross sections indicated by the subscripts.

2. 5.

Computing Machines.

The solutions to the temperature equation, Eq. (6),

and the velocity

equation, Eq. (24), are both obtained with the aid of IBM digital computers.

The temperature solutions are determined with the 704 electronic dataprocessing machine and the velocity calculations are performed with the

650 magnetic drum data-processing machine.

The former computer has

magnetic-core storage and over eight thousand storage registers with an

access time of 12 microseconds.

This machine stores information and

performes all of its arithmetic operations in the binary number system.

The 650 computer is a decimal machine, all information is stored

and all calculations are done in the decimal number system.

This machine

has magnetic drum storage with a capacity of 10, 000 or 20, 000 digits

and an access time that varies with the position of the read out heads with

respect to the position of the desired information on the drum.

3.

MECHANICS OF COMPUTER SOLUTIONS

This section presents a discussion of the programs used for determining (1) velocity values within a circular tube for laminar flow, (2) the

solution to the temperature equation, and,

(3) the values of local and

mean Nusselt numbers for a laminar-flowing fluid in a circular tube.

Because two different computers are used for these calculations, this

section can be divided into two distinct parts, one for the discussion of

the 650 program and the other for a description of the 704 programs.

3. 1.

Logical Block Diagrams.

To facilitate the programming of equations and, hence, the solution

of problems involving equations,

logical block diagrams are constructed.

These diagrams are obtained by placing arithmetic and logical operations

in boxes and connecting these boxes with vectorsthat indicate the direction

in which the calculation is proceeding.

The block diagram has two

purposes:

1.

It helps keep the over-all requirements of the problem

well in mind.

2.

It reduces the large problem that is difficult to visualize

and comprehend into a series of many smaller problems,

each of which may be readily visualized, understood,

and programmed.

The diagrams can be drawn at many levels.

Depending upon the complexity

of the problem being solved, a single box might represent one arithmetic

operation or a multitude of arithmetic operations.

3. 11.

Velocity Block Diagrams.

Because the calculation of the velocity from Langhaar's equation,

25

2

)ok

1 - R2k

.2

V(6, R)=

k=

Z

2

C12

+

2

, k! J

Wo

0

)2

. ...

,

(39)

(k + 2) (k + 1)

.k!

k= 1

2

2

involves determining values of two infinite series,

some criterion for

terminating both series must be established before any computation or

programming can proceed.

In Appendix B it is shown that all terms of

both series decrease monotonically for k greater than or equal to two.

Therefore,

because k is always two or greater, both series are terminated

by assuming that all fractional terms less than some quantity

neglected, where

A can be

A is defined as

A

A

-f

5x10.

The exponent f in the definition is one plus the number of significant

digits desired in the numerator and denominator of V.

Also, because the

number of significant digits in a quotient is equal to the number of

significant digits in either numerator or denominator whichever is smaller,

f plus one is the number of significant digits desired in the velocity V.

Figure 5 is the complete logical block diagram for the velocity

calculations.

The blocks labeled 00 and 10 in Fig. 5 are expanded and

redrawn in Figs. 6 and 7 respectively.

3. 12.

Diagrams for 704 Solutions.

The logical block diagram for the complete 704 solution, Fig. 8, is

composed of five major blocks.

ture solution,

These blocks represent (1) the tempera-

(2) the evaluation of the mean fluid temperature,

(3) the

26

READ

AN H 5ET

5ELECr y

AND

SET

'R=0

SET

|N v V = 0

SET

M=I

BLOCK 00

'YES

-R

VNK= -

-7

K.K

REPLACE'S

K

YES

SLOC< 10

xf2

VD - K!

(Kf 2}X+ 1)

R + 0.1

R EPLA CES

,q

DK

PCH

R$ V4 L

R EPLA C S

{YES

Lv

Fic. 5.

14K<

A

VIN

No

Lo&lciAL BLocK

DIAGFM

ro'

VELOCTrY CAqLCULArION

K 2

K!

RK R -RK- 1

FiG. 6.

B1LOCK

00

FOR VELOCITY

C A LCU L ATION

(i

Fi. 7.

(T K

2

ja)

(K+-

l)

BLOCr< 10 FOR

CA LCULATION

VELOCITY

determination of the temperature gradient at the wall, (4) the calculation29

of the local Nusselt number, and (5) the calculation of the mean Nusselt

number.

Each of these blocks can be subdivided.

However, the third

and fourth blocks represent straightforward algebraic manipulations and

the fifth block is very similar to the second block.

first and second blocks are expanded.

Therefore,

only the

Figures 9 and 10 represent the

temperature solution and the evaluation of the mean fluid temperature

respectively.

3. 2.

650 Program for Langhaar Velocity Profiles.

With the aid of the logical block diagrams Eq.

for the 650 magnetic drum data-processing machine.

(24) was programmed

An optimized

program was assured by subscribing to the rules of coding for the Symbolic

Optimum Assembly Program (S. O. A. P. ).

Because the parameter

X is generally a mixed number, the floating

point subroutines of the MIT Selective System (MITSS) were used.

Thus,

the need for scale factoring and for shifting decimal points either before

or after performing fixed point multiplication or division was eliminated.

In this manner, the time ordinarily needed for coding the problem was

reduced and the program was simplified.

However, no real time advantage

was gained because the floating point routines require more machine time

than the fixed point routines.

The assembled program is outlined here:

1.

Initially, seven values of X are read into the machine and

placed in appropriate storage registers.

2.

The first of the seven values of

Y

is selected and R is set

equal to zero.

3.

The selected value of X is operated upon to obtain the value

0

AND INITIAL

INFORMATION

T-EMPERATUR E DISTRIUTION

READ IN VELOCirY

L=O

SET

BLOCK

00

1

RL+AL

T,L+AL

REPLACE

BLOCK

7

'fl TR+AR,L + fa TR,L t+liTR-AR,L

4 TAR.,L +

T

R

0

2 'O,L

WITH TRL+4L

10

Tr

VT) R+AR+ 4(AVT)

+ (RV T R-AR]

R 0.I

BLOC/

20

-- 3

R

BLOCK

30

U/JT%

-'~Rl

flu

\

7- - .- rY-

1BLOCK

40

L-ATL

Nu,= 3

PRINT

AL

OUT

N

+ NVL.

T

"I

AND

L+2 AL

+

Nu4_

, +, L 7-y7 4aL ,

Nux,

iVlm

R EPLACES

L+AL

F~io...

LIiCAL fBLoerw

DIAGRAM

FoR

704

SOLUTION

31

PcMO

G.

~

OAL*L

4

Z 4L

7ARL

REPLACES

41 V

A R +Z

I7--

-A)

YK()(A)(?

RSL+AL

IR+,AR,L

R =.

OYE

Fi.

1BLOCK

00

o

R-ARL

TRL

704

NO

T EMP ERA TURre

C ALCULATIONS

32

S ET

R 0.1

(RvT)

R +2?R

R EFLACES

EIIR

-4(RVT)

(-vr)

T

=(RVT)RA2

- q(RvT)

+ (Rvr)

NO

1 qo.q

Yes

I7

r =PA

K

Fi. 10.

BLOCK 10 rom 704 MEAm FLu

Tr-eMPATURE

CA LCUL AT 1 ION

I

33

of V at the radius R and the result of this calculation plus

some identification is punched on an IBM card.

4.

The parameter R is indexed and control is transferred

back to (3).

After R has been indexed nine times, control

is transferred to the next part of the program step (5).

5.

The machine selects the next value of Y , sets R back to

zero, and transferres control back to (3).

This procedure

is repeated six times, thus using all seven values of 6 and

the program then continues with step (6).

6.

A new card is read into the machine and seven new values

Control is then

of X are placed on the magnetic drum.

transferred back to (2).

This procedure is repeated until

the read card hopper is empty, at which time a read light

is energized and the program is stopped.

All machine results obtained in this study were for

(40)

A= 5(10 4).

Hence, the calculated values of velocity V used for the temperature solutions.

are good to three decimal places.

3. 3.

704 Programs for Heat Transfer Solutions.

With the aid of block diagrams, Figs. (8),

(9), and (10), the heat

transfer problem was coded for the 704 electronic data-processing machine.

The program was written in the standard symbolic coding language agreed

upon by members of the Share organization so that the Share Assembly

Program (SAP) could be utilized.

All arithmetic operations are performed

on floating-point numbers with floating-point instructions and index

registers are used to count and regulate cyclic processes.

34

The 704 programs are composed of five major parts, the calculation

at any cross section L for (1) the temperature distribution,

fluid temperature,

(3) the temperature gradient at the wall,

Nusselt number, and (5) the mean Nusselt number.

(2) the mean

(4) the local

The assembled program

for the constant wall temperature solutions is outlined here.

Initially:

1.

The velocity data and all other starting information are

read into the machine.

Temperature Distribution:

2.

The coefficients f2 and f 4 are determined for R equal to

zero and the center-line temperature is evaluated.

3.

The radius R is indexed and the coefficients f , f , and f

2

3

are calculated.

4.

The temperature at the indexed radius is obtained and

control is transferred back to (3).

This procedure is

continued, always using the proper velocity values, until

the entire temperature distribution at section L is determined.

5.

The program then continues with step (5).

The temperature distribution at L replaces the distribution

at L - A L.

Hence, the first time through the program

the temperature distribution at A L replaces the starting

temperature distribution.

Mean Fluid Temperature:

6.

After step (5) is completed, the mean fluid temperature

is computed with Simpson's

rule by averaging the product

VTR over the tube cross section.

35

Temperature Gradient at the Wall:

7.

The gradient at the wall is evaluated by assuming that the

temperature distribution between R equal to 0. 8 and the

wall is a parabola.

Hence, the gradient is the derivative

of the temperatuire evaluated at R equal to 1. 0 and is

obtained from Eq.

(37).

Local Nusselt Number:

8.

The local Nusselt number at section L is determined by

dividing twice the temperature gradient at the wall by the

wall temperature minus the mean fluid temperature.

All

values of local Nusselt number are preserved in the

machine s-o that the mean Nusselt number can be determined at any section L.

Mean Nusselt Number:

9.

The mean Nusselt number at section L is obtained with

Simpson's rule by averaging the local Nusselt numbers

over the tube length between section L and the tube

entrance.

For the computer solutions, the local Nusselt

number at the tube entrance is assumed to be 30.

This

figure is obtained by evaluating Eqs. (10) and (37) at the

tube entrance.

However, this assumption appears to be

rather poor for many Prandtl numbers.

Hence, mean

Nusselt numbers are also evaluated on a desk calculator

with the values of local Nusselt numbers obtained on the

704 and with a starting mean Nusselt number at L = 0. 004

as determined from the Pohlhausen flat plate solution,

Eqs. (1) and (2).

Finally:

10.

After the calculations at section L are completed, the

values of L, T

, ( 4 T/a R)R = 1, Nu , and Nu

mx

written on magnetic tape.

m

are

Also, at some fixed interval

of L other than A L the temperature distribution TR is

placed on tape.

The length L is incremented and control

is transferred back to (2).

This cyclic process is re-

peated until f 2 becomes negative or until the desired

number of length increments

A L have been considered.

When the program stops, the magnetic tape that contains

the results is taken to special off-line equipment and a

list out of the results is obtained.

The constant temperature difference solutions proceed as the constant

wall temperature solutions with the following exceptions:

1.

After the mean fluid temperature is found, the wall temperature at L is obtained by adding one to the mean fluid

temperature.

This value of wall temperature then re-

places the value at L - A L.

2.

Because the difference between the wall temperature

and the mean fluid temperature is always one, the local

Nusselt number is obtained by multiplying the temperature

gradient at the wall by two.

The 704 program for the parabolic-velocity,

constant wall-temperature

solutions is much simpler than the two programs discussed in the preceding

paragraphs.

of R alone.

For the parabolic-velocity solutions, the velocity is a function

Hence, the f. functions do not need to be calculated at each

1

station along the tube length but can be determined at the first station, stored

in the machine, and used at all stations.

This simplification plus the fact

that a very small amount of velocity data need be stored in the machine

greatly reduces the complexity of the program for parabolic-velocity solutions.

3. 4.

650 Test Solutions.

To check-the assembled program and to determine whether or not

production running can be started, a test solution for

=

2, that was cal-

culated by hand, is compared with a trace of the 650 program.

The test

solution values and the values obtained from the trace are tabulated in

Table 2.

A comparison of these values reveals that the machine numbers

are in agreement with the test solution.

Therefore, it is assumed that no

errors were made in the final assembly of the program and production

running is started.

After completing the production runs a comparison of machine results

is made with some values of center-line velocity that are listed in

Langhaar's paper.

5

The following values are compared:

Langhaar

650 Results

(4x/D)/Re

1.9800

1.9799860

.227

1.9434

1.9434035

.156

1.8573

1.8572992

.095

1.3514

1.3514404

.010

When the 650 results are rounded off to four places, the machine values and

those of Langhaar are in exact agreement.

Hence, it is assumed that the

program accomplished what it was designed to agcomplish, namely determine the velocity V at various radii R and lengths L.

38

Table 2.

Comparison of 650 Computer Solution

and Test Solution for W= 2.0.

Program Position

End of 1st Loop

Computer Solution

Test Solution

-1. 6616667x10~

1

-1. 6616667x10

1

2nd Loop

-2. 0333333x10-2

-2.0333333x10-2

3rd Loop

-8. 8888900x10~ 4

-8.8888900x10

4th Loop

4. 4212963x10~4

4. 4212963x10 44

1.8573035

1.8572992

Final Value

4

704 Test Solutions.

3. 5.

Two test solutions are used for the 704 computations.

solution was obtained with a desk calculator for Pr

tube wall temperature.

of

=

The first test

1. 0 and a constant

Calculations were made for the first two increments

A L, that is, values were obtained for L =

A L and L = 2 A L.

This

solution is used to check the assembled program and after a satisfactory

machine solution is obtained production running is started.

The test

solution and machine results appear in Table 3.

The second test solution was obtained by W. M. Kays at Stanford

University and is used to verify the 704 program.

Kays computed a solution

for Pr = 0. 7 and a constant tube wall temperature with numerical techniques similar to those used in the present study.

Table 4 is a tabulation

of Kays' results and the 704 results obtained for Pr = 0. 7 and a constant

tube wall temperature.

From this table it is apparent that the machine

results agree very well with the test solution.

are not in exact agreement.

However, the two solutions

A large initial discrepancy is present

because the incremental length A L used for both solutions was not the

same.

For Kays' solution A L = 0. 001 was employed for L = 0 to L = 0. 010,

and A L = 0. 002 for L > 0. 010, whereas for the 704 solutions A L = 0. 00143

was employed for all L.

Kays verified his solution with experimental data.

Therefore, the foregoing discussion indicates that the 704 program is

correct and can be used to compute within the region of interest heat

transfer solutions for laminar flow in circular tubes.

40

Table 3.

Test Solution and Computer Solution

for Pr = 1. 0, Langhaar Velocity

Profiles, and Constant Wall Temperature.

L= .002

L= .001

.Test Solution

Radius

Computer Solution

Test Solution

Computer Solution

.Temperature

1. 00000

1 .00000000

1 .00000000

1 .00000

1 .00000

1.0&0000000

.99999985

0.2

1. 00000

.99999992

.99999

.99999992

0.3

1. 00000

1 .00000000

.99999992

0.4

1. 00000

.99999992

.99999

.99999

0.5

1. 00000

.99999992

1 .00000

.99999985

0.6

1. 00000

.99999992

1 .00008

.99999992

0.7

1. 00099

1 .00000000

1 .00080

1.00000000

0. 8

99999

.99999992

1 . 01124

1.01124864

0.9

1. 11430

1 .11431486

1 .21116

1.21118170

Q

.1. 00000

0.1

.99999985

Mean Fluid Temperature

1.01993

1.01992723

1.04155

1.04156030

Gradient at Wall

12.7140

12.7137023

10.8330

10.8326090

'Local Nusselt Number

25. 9451

25. 9444049

22. 6052

22. 6046752

.Mean Nusselt Number

16. o642

16.0637156

41

Kays' Solution and 704 Solution

0.7, Langhaar Velocity

for Pr

Profiles, and Constant Wall Temperature.

Table 4.

Kays

704

.004

18.46

17.45

.010

11.31

10.87

.020

7.90

.030

6.53

6.52

. 040

5.82

5.80

.050

5.34

5.34

.060

5.02

5.01

.070

4.75

4.7 6

.080

4.57

4.57

.090

4.42

4.41

.100

4.29

4.29

.110

4.18

4.19

. 120

4.09

4.11

. 130

4.03

4.04

.140

3.97

3.98

.150

3.91

3.93

.160

3.88

3.89

.170

3.85

3.85

.180

3.82

3.82

.190

3.79

3.78

.200

3.77

3.76

.

RePr/(x/D)

Nu

Nu

(4x/D)/RePr

Kays

704'

1000

17.44

17.58

400

200

7.77

11.28

11.25

133.

100.

9.12

9.09

80.

66.

7.95

7.93

57.

50.

7. 19

7.18

44.

40.

6.67

6.66

36.

33.

6.27

6.26

30.

28.

5.96

5.96

26.

25.

5.72

5.72

23.

22.

5.52

5.52

21.

20.

RESULTS OF STUDY

4.

In this section the results obtained for particular Prandtl-numbers

are presented.

Only those results useful in heat exchanger design have

been included, other machine results have been deleted.

Also, because

the results are useless without some indication of their accuracy, a discussion of the accuracy of the numerical methods is included in this

section.

4. 1.

Velocity Results.

The velocity calculation was made for twenty-five hundred different

positions within a circular tube on the 650 magnetic drum data-processing

machine.

The calculations for cross sections close to the tube entrance

used the most machine time, twenty-nine seconds per cross section.

The

shortest solutions used four and a half seconds for cross sections where

the velocity profile was very nearly developed.

The average solution

time was six and a third seconds and the total 650 time used for production

running was slightly over two hundred minutes.

A summary of the resultant velocity solutions appears in Table 5.

The values in this Table are good to at least three figures to the right of

the decimal point.

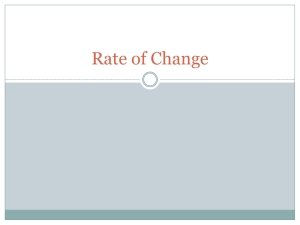

profiles.

Also, Fig. 11 is a plot of the generalized velocity

In this Figure,

V is plotted against the tube radius R with the

expression LPr as a parameter.

These profiles are invariant with

changes in Prandtl number.

The velocity values obtained from the 650 were used with the 704 to

compute heat transfer solutions for various Prandtl numbers and boundary

conditions.

Table 5.

Values of Langhaar Velocity

Profiles Obtained on 650.

(rounded off to three places)

4(x/D)

Re

RADIUS

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

.004

1.253

1.253

1.253

1.251

1.247

1.237

.010

1.351

1.350

1.347

1,340

1.326

1.300

.020

1.483

1.480

1.469

1.450

1.416

1.362

.030

1.577

1.571

1.554

1.522

1.472

1.396

.040

1.647

1.640

1.616

1.575

1.511

1.418

.050

1.703

1.693

1.665

1.615

1.540

1.434

.060

1.751

1.740

1.707

1.649

1.564

1.446

.070

1.790

1.778

1.741

1.677

1.584

1.456

.080

1.821

1.808

1.767

1.699

1.598

1.463

.090

1.846

1.832

1.789

1.716

1.610

1.469

.100

1.868

1.853

1.808

1.731

1.621

1.473

.110

1.887

1.871

1.824

1.744

1.629

1.477

.120

1.903

1.886

1.837

1.755

1.636

1.481

.130

1.916

1.900

1.849

1.764

1.643

1.484

.140

1.928

1.911

1.859

1.772

1.648

1.486

.150

1.938

1.920

1.867

1.779

1.653

1.488

. 160

1.947

1.929

1.875

1.785

1.657

1.490

.170

1.954

1.936

1.881

1.790

1.660

1.491

.180

1.960

1.942

1.886

1.794

1.663

1.492

.190

1.965

1.947

1.891

1.797

1.665

1.493

.200

1.970

1.951

1.895

1.800

1.667

1.494

.210

1.974

1.955

1.898

1.803

1.669

1.495

.220

1.978

1.959

1.902

1.806

1.671

1.496

.230

1.981

1.962

1.904

1.807

1.672

1.496

.240

1.983

1.964

1.906

1.809

1.673

1.497

.250

1.986

1.966

1.908

1.810

1.674

1.497

Table 5.

(continued)

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.215

1.162

1.036

.733

1.251

1.159

.983

.646

1.275

1. 138

.918

.565

1.284

1. 118

.876

.521

1.287

1.103

.847

.493

1.288

1.090

.826

.472

1.288

1.079

.807

.455

1.287

1.070

.793

.442

1.287

1.063

.782

.432

1.286

1.057

.773

.424

1.285

1.051

.765

.418

1.285

1.047

.758

.412

1.284

1.043

.753

.407

1.284

1.040

.748

.403

1.283

1.037

.744

.400

1.283

1.035

.741

.397

1.283

1.033

.738

.395

1.282

1.031

.735

.393

1.282

1.030

.733

.391

1.282

1.028

.731

.389

1.281

1.027

.730

.388

1.281

1.026

.729

.387

1.281

1.025

.727

.386

1.281

1.025

.726

.385

1.281

1.024

.726

.385

1.281

1.023

.725

.384

2.o

Re

.8.

.250

/.64

'.4

4/D-

K

V

v-rn

.8

L Pp=

Re

=.

004

.6-

.4-

2

/o

.6

FiG. /I.

.6

-4

GENERALIZED

.Z

6

.I

VS-LOCITY

.4

.6

.

1.o

PRqoF-1LEr, L-ANrH ARR

4. 2.

Heat Transfer Results.

The 704 electronic data-processing machine solutions are summarized

in Tables 6 through 15.

The constant wall temperature solutions appear in

Tables 6 through 10 and the constant temperature difference solutions appear

in Tables 11 through 15.

Solutions were obtained for Prandtl numbers

0. 5, 0. 7, 1. 0, 2. 0, 5. 0,

10. 0, and 50. 0.

However, the solutions for

Pr > 5. 0 are not presented in this report.

For Pr > 5. 0 the velocity pro-

file develops much faster than the temperature profile and the idealization

of fully developed or parabolic flow yields adequate results within the region

of interest in heat exchanger design.

Two columns of each of these Tables are devoted to mean Nusselt

numbers.

The values obtained from the 704, "704 Num", were obtained by

making the simplifying assumption that for all Prandtl numbers the local

Nusselt number at the tube entrance is 30.

This particular value was

chosen because it is consistent with Eqs. (10),

(12), and (37).

However,

because errors are propagated downstream and because near the tube

entrance finite difference errors are large, the mean fluid temperature

changes rapidly,

and the radial enthalpy flux, neglected in the reduced

temperature equation, may be of some importance, this approach does not

yield accurate results.

A more accurate method is to employ an approximate

solution in the vicinity of the tube entrance and then to use Eq. (12) and

the local Nusselt numbers to obtain the downstream mean Nusselt numbers.

The values appearing in the columns headed "Nu m" were obtained on a

desk calculator using the Pohlhausen flat plate solution to obtain a starting

mean Nusselt number at RePr/(x/D) = 1000.

The computer results are also summarized in Figs. 12, 13, 14, and

15.

The constant wall temperature results are plotted in Figs. 12 and 14,

417

Table 6.

Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Wall Temperature,

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 0. 5.

4 (x/D)/(Re Pr)

Nu

.004

17.02

22. 40

.007

13.11

20. 35

.010

10.91

17.09

.020

7.91

13.05

.030

6.65

11.12

.040

5.93

-9.89

.050

5.46

9.05

.060

5. 12

8.42

.070

4.87

7.93

.080

4.67

7.53

.090

4.52

7.21

.100

4.39

6.93

.110

4.28

6.69

.120

4.20

6.49

.130

4.12

6.31

.140

4.06

6. 15

. 150

4.01

6.01

. 160

3.96

5.89

.170

3.93

5.77

.180

3.89

5.67

. 190

3.86

5.57

. 200

3.84

5.49

. 210

3.82

5.41

.244

3.76

5.18

. 278

3. 72

4.99

704 Nu

m

Nu

m

24.5

RePr/(x/D)

1000

571.4

17.84

400

200

11.41

133.3

100

9.24

80

66.7

8.06

57.2

50

7.31

44.4

40.0

6.78

36.4

33.3

6.38

30.8

28.6

6.07

26. 7

25.0

5.82

23.5

22.2

5.62

21. 1

20. 0

5.45

19.0

16.4

5.04

14. 4

Table 7.

4(x/D)/RePr

Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Wall Temperature,

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 0. 7.

.Nux

704 Nu

m

. 004

17.45

22. 79

.007

13.13

19.75

.010

10.87

17.26

.020

7.77

13. 11

.030

6.52

11.10

.040

5.80

9.86

.050

5.34

9.00

.060

5.01

8.36

.070

4.76

7.86

.080

4.57

7.46

.090

4.41

7. 13

.100

4.29

6.85

.110

4.19

6.61

.120

4.11

6.41

.130

4.04

6.24

.140

3.98

6.07

.150

3.93

5.93

.160

3.89

5.80

.170

3.85

5.69

.180

3.82

5.57

.190

3.80

5.49

.200

3.78

5.41

.210

3.76

5.33

.280

3.68

4. 92

.350

3.65

4.67

.Nu

m

-23. 8

(RePr )/(x/D)

-1000

571.4

17.58

400

zoo

11.25

133.3

100

9.09

80

66.7

7.93

57.2

50

7. 18

44. 4

40.0

6.66

36.4

33.3

6.26

30.8

28.6

5.96

26.7

25. 0

5.72

23. 5

22. 2

5.52

21.1

20.0

5.35

19.0

14. 3

4.69

11.4

49

Table 8.

4(x/D)/(RePr)

Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Wall Temperature,

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 1. 0.

.Nu

704 Nu m

..004

-17.47

.22. 96

.007

13. 04

19. 61

.010

10..72

17. 22

.020

7.60

13.04

.030

6.36

10.99

.040

5.66

9.74

.050

5.21

8.88

.060

4.89

8.24

.070

4.65

7.74

.080

4.46

7.34

.090

4.32

7.01

.100

4.20

6.74

.110

4.11

6.50

.120

4.03

6.30

.130

3.97

6.12

.140

3.91

5.97

.150

3.87

5.83

.160

3.83

5.71

.170

3.80

5.59

.180

3.77

5.49

.190

3.75

5.40

.200

3.73

5.32

.210

3.71

5.24

.230

3.69

5.11

.250

3.67

4.99

Nu

21.5

RePr/(x/D)

1000

571. 4

16. 64

400

200

10.82

133.3

100

8.77

80

66.7

7.67

57.2

50

6.96

44.4

40.0

6.46

36.4

33.3

6.08

30.8

28.6

5.79

26.7

25.0

5.56

23. 5

22. 2

5.37

21. 1

20. 0

5.22

19. 0

17. 4

4.97

16. 0

5c0

Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Wall Temperature,

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 2. 0.

Table 9.

4(x/D)/RePr

Nu

..004

17. 15

22. 88

. 007

12. 57

19. 33

.010

10.24

16. 92

. 020

7.23

12. 67

.030

6.05

10. 64

.040

5.40

9. 40

.050

4.98

8. 56

.060

4.69

7. 94

.070

4.47

7. 45

.080

4.31

7. 07

. 090

4.18

* 100

4.08.

.110

4.00

.120

3.94

6.

6.

6.

6.

x

704 Nu

m

76

Nu

m

19.20

08

1000

571.4

15.47

400

200

10.18

133.3

100

8.28

80

66.7

7.26

57.2

50

6.61

44.4

40.0

49

27

(RePr)/(x/D)

6.15

36.4

33.3

Table 10.

4(x/D)/RePr

.Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Wall Temperature,

.Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 5. 0.

Nu

704 Nu

m

. 004

.16. 16

22. 33

.007

11.62

18.59

. 010

9.46

16.14

.020

6.74

11.98

.030

5.71

10.04

.040

5.15

8.88

.050

4.79

8.10

Nu

m

16. 90

RePr/(x/D)

.1000

571.4

14.01

400

200

9.35

133.3

100

7.68

80

52

Table 11.

Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Temperature Difference,

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 0. 5.

4(x/D)/RePr

Nu

.004

17.65

22. 75

.007

13.81

20. 79

.010

11.62

17.64

. 020

8.61

13. 69

.030

7.37

11.78

. 040

6.67

10. 57

.050

6.21

9.75

.060

5.88

9. 13

. 070

5.64

8.65

.080

5.45

8.26

.090

5.30

7.94

. 100

5. 18

7. 67

.110

5.08

7.44

.120

5.00

7.23

.130

4.92

7.05

. 140

4.87

6.90

.150

4.82

6.77

. 160

4.78

6.64

.170

4.74

6.53

.180

4.71

6.43

190

4.68

6.34

.200

4.66

6.26

.210

4.64

6. 18

x

704 Num

Nu

24.50

RePr/(x/D)

1000

571.4

18.25

400

200

12.02

133.3

100

9.90

80

66. 7

8.75

57. 2

50

8.02

44.4

40. 0

7.50

36.4

33.3

7.12

30.8

28. 6

6.82

26.7

25. 0

6.58

23.5

22.2

6.38

21.1

20.0

6.22

19. 0

Table 12.

4(x/D)/RePr

Nu

-

x

Summary of Numerical Solutions

Constant Temperature Difference,

Langhaar Velocity, Pr = 0.7.

704 Nu

M

Nu

23.8

004

17.97

23. 23

007

13.75

19. 97

010

11.52

17. 72

020

8.43

13. 67

030

7.19

11. 70

040

6.49

10. 47

050

6.04

9. 68

060

5.72

9. 00

070

5.48

8. 52

080

5.29

8. 12

090

5.15

7. 80

10.0

5.04

7. 53

110

4.94

7. 30

120

4.87

7. 10

130

4.81

6.95

140

4.76

6. 93

6. 77

150

4.71

6. 63

6.66

160

4.67

170

4.64

6. 52

6. 41

180

4.62

6. 31

190

4.59

6. 22

200

4.57

6. 14

210

4.56

6. 06

280

4.49

5. 68

350

4.46

5. 43

RePr/(x/D)

1000

571.4

17.95

400

200

11.81

133.3

100

9.70

80

66. 7

8.56

57.2

50

7.84

44.4

40. 0

7.33

36. 4

33.3

30. 8

28.6