Sprawl, Density Development John R. Ottensmann

advertisement

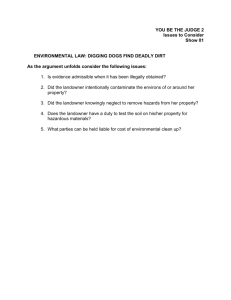

Urban Sprawl, Density Values Land of and the Development John R.Ottensmann The character of the residential development occurring at the periphery of a metropolitan area has extensive and diverse economic and social implications. The kinds and prices of housing produced, the population groups served, and the cost and problems of providing public services are all determined by the workings of the development process. An understanding of this process requires an examination of the relationships between land prices and the location and intensity of development. Urban sprawl-the scattering of new development on isolated tracts, separated from other areas by vacant land-is frequently cited as one negative consequence of the development process. The separation of residential areas by vacant land leads to increased costs in providing utilities and other public services. Residents are forced to travel farther to engage in most activities, using more energy resources and producing more air pollution. The scattered subdivisions bring the negative impacts of urbanization to far larger areas of formerly agricultural or wilderness land. And finally, although this effect is impossible to quantify, many have strenuously objected to sprawl on aesthetic grounds, arguing against the formless character of typical urban development. Urban sprawl is not without its defenders. Lessinger [1962] argued that the scatter of new development might prevent the development of large, homogeneous residential areas that would be socially segregated and ultimately become large, homogeneous slums. Boyce [1963] suggested that sprawl retains an element of flexibility for future urban development appropriate under conditions of uncertainty and imperfect knowledge. The reservation of land for later development in more intensive uses, either residential or commercial, could produce an urban pattern that may be more efficient in the long run, based on recent theoretical work by Ohls and Pines [1975]. A basic discussion of the nature of sprawl has been provided by Harvey and Clark [1965]. Clawson [1962] and Sargent [1976] have suggested the importance of landowner speculation in the process. Bahl [1968] considered the role of the property tax, while Archer [1973] attributed sprawl to the failure of the residents of the new areas to be confronted by the full costs of development. Land values play a critical role in the allocation of land, thereby shaping the The author is Assistant Professor, Program in Social Ecology, University of California,Irvine. He wishes to thank Professors J. Bonham, F. Stuart Chapin Jr., A. Allan Schmid and an anonymous refereefor theircommentsand suggestions. 'For a summary of the costs of sprawl, see Clawson [1971, pp. 140, 152-59, 320]. The most comprehensivereviewis the report by the Real Estate ResearchCorporation[1974]. Land Economics ? 53 * 4 * November 1977 390 Land Economics pattern of development. Maisel [1963], Neutze [1970] and Muth [1971] have provided theoretical statements about the determination of land values that are particularly applicable to the issues of concern here. Empirical studies of differences in land values between urban areas include those of Maisel [1964], Mittelbach and Cunningham [1964], Schmid [1968] and Witte [1975].2 The density at which land is developed for residential purposes is the final important characteristic of development at the urban periphery. Harrison and Kain [1974] have examined the densities of fringe development over time and the cumulation of this incremental development to form the urban pattern. Two studies, by Neutze [1968] and Schafer [1964], have focused on the development of apartments at the urban fringe.3 This paper addresses this triad of characteristics of peripheral urban residential development: urban sprawl, land values and density of development. First, an account of the development process is given. Hypotheses are developed involving the variations of these three factors across urban areas. Finally, the predicted relationships between the rate of urban growth, land values and density of development are tested using data from the past two decades for metropolitan areas in the United States. THENATUREOF PERIPHERALGROWTH The desire for accessibility to the urban center might be expected to result in continuous development extending out from that center, since people seek more accessible locations and are willing to pay more for them (see, for example, Alonso [1964] ). This must be the case, however, only in static situations or if landowners are shortsighted and consider just the returns from development in the current p.eriod. More reasonably, owners compare the returns from immediate development with their expectations of the returns from development in the future, deducting the costs of holding the land and discounting the returns to their present values.4 As a result, some owners may withhold their land and forgo current development while development occurs on less accessible land farther from the center. For example, current demand might support only the development of single-family housing beyond a certain distance. Future urban growth, however, could generate a demand for multifamily housing yielding far higher returns, causing the most accessible land to be withheld during the current period.5 An explanation of urban sprawl requires more than expectations of future growth. Given the conventional assumptions, similarly situated landowners should face a common future and should reach the same decisions with respect to development. But landowners vary widely with respect to their situations, knowledge and attitudes, which affects both future expectations and real and 2Many more studies have dealt with intraurban variations in land values. A good introduction to this work is Mills [1969]. For more recent references, see Witte [1975]. 3As was the case with land values, many studies have dealt with intraurban variations in population density. See, for example, Muth [1969] and Mills [1972]. 4Bahl [1968] has specified the conditions under which a landowner should either withhold his land, develop it or sell it. SOhls and Pines [1975] have demonstrated that such skipping of close-in land in favor of higher-density development at a later time may prove to be more efficient for the society in the long run. Ottensmann: UrbanSprawl perceived holding costs. Some important differences include landowner incomes, income tax positions, alternative investment opportunities, the possible use of the land in agricultural production and eligibility for preferential property tax treatment.6 These differences will produce variations in landowner decisions to develop or withhold their land, resulting in the fine-grained pattern of urban sprawl that is observed as development occurs at the periphery of urban areas.7 Differences in the levels of future expectations may be important in accounting for variations in the patterns of residential growth between cities. Hypotheses are derived involving the relationships between expectations, urban sprawl, land values and densities of current development. Consider two identical urban areas with the same patterns of demand for residential development in the current time period. Considering only this current demand, landowners in comparable locations would obtain similar returns from current development in the two cities. The cities differ only in the levels of expectations of the landowners: In one city, only slow growth and low levels of future residential demand are anticipated after this current time period, while rapid growth and high demand are expected in the other. Thus, landowners in the first city will tend to have lower expected present values of returns from future development than their more optimistic counterparts in the second city. There will, of course, still be variations in landowner expectations within each of the cities. When the landowners compare their initial expectations regarding returns from current development (the same in both cities) with the anticipated returns from future development, the patterns 391 of decisions will vary between cities. Given the lower levels of expected future returns, current development will be more attractive to a higher proportion of landowners in the first city. The higher future demand in the second city will be more appealing, causing more of these owners to withhold their land in favor of future development. (This decrease in the supply of land for current development will produce an increase in land prices and returns from current development, enticing some of the reluctant owners back into the development of their land before an equilibrium is reached.) This forms the basis for the first hypothesis: The quantity of land withheld from current development-the amount of urban sprawl-should vary directly with the levels of expectation concerning future residential demand. Put another way, landowners in rapidly growing cities will reserve more land for future development. The more growth they expect, the greater their tendency will be to sit tight and wait for higher returns to their land. The withholding of land decreases the supply available for current development at any distance from the center. This will force the price for land up (also causing some additional land to be released for 6Clawson [1962] and Kaiser et al. [1968] provide good accounts of the factors which influence landowner behavior. 7The argument assumed the existence of large numbers of landowners at any given location in order to discuss the proportions with higher or lower expectations who would or would not withhold their land. With small numbers of landowners at any location, the argument can still be used if their expectations are assumed to be subject to a probability distribution comparable to the distribution of expectations among the larger number of landowners. Then the large landowners' decisions concerning future expectations and the withholding of land would be probabilistically determined, still producing random variation and sprawl. 392 current development). Thus the second hypothesis: Land values should vary directly with the levels of expectation concerning future residential demand. In those cities that are growing more rapidly, higher future expectations will force current land values up. A higher price for land will cause developers to use less land in the production of housing, substituting other inputs for land. The third hypothesis is, then, as follows: Density of residential development on land that is developed (and not withheld) should vary directly with land values and with levels of expectation concerning future residential demand. Ironically, the faster growing cities, while having more sprawl, will actually be denser in those areas that are actually developed. The traditional assumption of employment being concentrated in a single center has become less tenable with the decentralization of commercial and industrial activity in most large urban areas. The development of multiple centers of employment near the edge of the fully developed portion of the city would not alter the desire of new residents to locate close to their places of work. However, the generally shorter commuting distances would lessen the resistance to locating at even greater distances from the center, increasing demand farther out and further encouraging dispersed development. In addition, the emergence of the peripheral centers might increase the potential for future higher-density development in their vicinities, creating a greater incentive to withhold land. Thus, decentralization of employment would be expected to lead to even more urban sprawl. In summary, when expectations about future development potential are high, Land Economics more land will be withheld from development, land values will be higher, and the densities in developed areas will be higher. More will be done on less land, at higher prices, as the owners wait for still higher expected returns from future development. THEHYPOTHESES TESTING The second and third predictions outlined above, involving variations in land prices and density of development across urban areas, have been tested empirically. The procedures followed and the variables used in these tests are described in this section. The first of the hypotheses involved the withholding of land from development to produce urban sprawl; unfortunately no data could be found that were appropriate to examine the prediction in this case. A model incorporating the two hypotheses in the form of linear regressions is tested using data from Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas (SMSAs) in the United States. For the first set of regressions, measures of land value serve as the dependent variable. Expectations of future development measured by rates of population growth are expected to be positively related to land values. Two additional independent variables are also included in these regressions-population and income. Larger cities have greater aggregate demand for residential space, and higher incomes allow individuals to offer more for such space. Thus, both variableswould be expected to be significant factors affecting land values and should be positively related to these values. For the second set of regressions, the density of current development is the dependent variable. Land values and population growth should both, as hy- Ottensmann:UrbanSprawl pothesized, be positively related to the density of development. Population should also be positively related, since the greater demand for space in large cities forces more intensive use. The role of income is less clear in this case: Higher incomes could increase land values and hence densities, but could also enable households to purchase more space. A variety of land price data for metropolitan areas in the United States has been assembled by Schmid [1968]. The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) has gathered information from its members regarding the average price of raw suburban land purchased by them for their own use in residential development in a large number of urban areas for 1960 and 1964. These data on land values per acre should be indicative of the overall level of prices for land for new residential development in each SMSA, even though they cover only the activities of the NAHB members. Like all attempts to collect land value information, these NAHB data are undoubtedly affected by significant inaccuracies and problems in coverage. Thus, it was felt to be appropriate to consider alternative sources of information. Data on the prices of lots sold for new residential development are an alternative. Such information is somewhat easier to come by, but suffers two shortcomings: lot sizes vary and other development costs affect the final price of a lot. Therefore, lot prices can be only imperfect measures of the variation in land values across urban areas. NAHB data on lot prices in 1960 and 1964 (covering the prices of developed lots for single-family home building reported by NAHB members in surveys) and Federal Housing Administration (FHA) data on lot prices in 1950 and 1964 (covering the prices for developed lots for single-family homes 393 with FHA-insured mortgages in each SMSA) are included in the tests of the models. These data also cover only a portion of the land market, but provide alternative tests and extend the temporal range of the tests.8 Following the example of Harrison and Kain [1974], the percentage of new housing units constructed during a decade as single-family dwellings is taken as the surrogate measure for density of development. Of course, percent singlefamily development is inversely related to the density of development, so the direction of the hypothesized relationships must be reversed. While variations do occur in the densities at which both single-family and multifamily development take place, the choice between these types undoubtedly accounts for most of the variation in development densities across SMSAs. The data available refer to the SMSAs as a whole and are therefore affected by central city redevelopment. However, data for the SMSA fringes would have missed significant peripheral development occurring within central cities.9 As mentioned earlier, rates of population growth are taken as measures of landowner expectations regarding future development. The current rate of growth in the metropolitan area was considered to be the major factor which landowners could observe and, hence, the major factor affecting expectations. Landowners in a rapidly growing city will be more 8 All of the land price variables were obtained from the appendix tables in Schmid's study [1968, pp. 60-93]. He obtained the information from a variety of FHA and NAHB documents for which he provides citations. No corrections were made for inflation; this should be considered when interpreting the results. 9The percentages of new construction in singlefamily units in each SMSA were obtained from the U.S. Bureau of the Census [1963, Table 6; 1973a, Table A-6]. 394 likely to anticipate rapid growth in the future. Such a measure may not be ideal, but it is difficult to imagine that expectations will not be related at all to experience. Finally, the last two independent variables are the SMSA populations and median family incomes at or prior to the time of development being considered. Thus, 1950 values are used with 1950 land prices and percent single-family development during the 1950-1960 decade, and 1960 values are used with 1960 and 1964 land prices and 1960-1970 development. The SMSA boundaries in effect at each census were employed, as it was felt that these areas and figures were most relevant for landowner decisions at those times.10 Due to differences in the data sources, various data were available for different numbers and sets of SMSAs. Depending upon the variables employed, regressions could include anywhere from just over fifty to nearly two hundred SMSAs. A full set of data was available for fifty-one SMSAs. Comparisons were made of the results of regressions run with both this limited sample and with all of the cases available for the particularvariables. Differences were relatively minor and did not affect the substantive interpretations of the results. Therefore, for simplicity and comparability, all of the results reported here refer to the same sample of fifty-one SMSAs. l Different functional forms were used in regressions for some of the variables. For example, a logarithmic transformation of the population variable was tested in all of the regressions. None of the tests was conclusive. Examinations of residuals favored neither form. All of the variables in the regressions reported here are in arithmetic form. The final issue involved the selection Land Economics of the appropriate time period of population growth to use in representing the level of landowner expectations. The initial supposition was that the level of a metropolitan area's population growth just prior to or during the period of development considered would most directly influence landowner expectations. However, should landowners exhibit rather more prescience than is expected, the rate of population growth in a future period would be a more appropriate measure of those expectations. Tests with alternative population growth measures failed to support a claim for any special powers of prediction by land' SMSA population changes, populations, and median family incomes were obtained from the U.S. Bureau of the Census [1953, Table 2; 1962, Table 3; 1973b, Table 3]. Schmid [1968, p. 51] conducted a multiple regression analysis using the same 1960 NAHB price data (with a larger number of cases). Schmid's dependent variable was percent appreciation of the land prices over farm land values. This is highly correlated with the land prices themselves, since farm land prices are much smaller and vary less. (However, any error in the farm land price data is magnified by this procedure, producing large variations in the percent appreciation variable.) The larger set of independent variables used by Schmid varied from the current independent variables in several ways. First, Schmid used data for both the cities and the urbanized areas, while the present tests use data for the SMSAs. The latter units are more commonly used and make possible the measurement of population change within fixed boundaries. The changes in urbanized area boundaries from census to census, combined with changes in the procedures used for their delineation from 1950 to 1960 (see Clawson [1971, pp. 23-25]), complicate their use. Second, Schmid uses multiple measures of population and land area for urban size and its change. Land area is meaningless for SMSAs, and single measures reduce problems of multicollinearity. Finally, Schmid includes measures of population density, fringe population and commutation to the central city. These also depend upon the locations of urbanized areas of central city boundaries, and they were not felt to be important to the formulation of the problem given here. " The sample of 51 SMSAs had a mean population in 1960 of 1,188,000 and a mean rate of population change from 1960 to 1970 of 19.3 percent, while the larger sample of 169 SMSAs had a mean population of 540,000 and a mean rate of change of 16.4 percent. Ottensmann:UrbanSprawl owners. The rate of population change from 1940 to 1950 was the better predictor of 1950 land values, while the 1950 to 1960 change best accounted for variation in the 1960 and 1964 land values. Densities of development, measured by the percent single-family units constructed in the 1950-1960 and 19601970 decades, were predicted best by regressions including rates of population change during those same decades. These are the population change measures used in the tests reported here. The hypotheses yielded two equations for the prediction of land price and density of development. Land price is seen as a function of expectations (measured by population changes) and other variables (population and income); density of development is seen as a function of land prices, expectations and the other variables. As they are stated, the equations constitute a recursive system. Land prices are determined by demand, both present and future, and in turn determine densities of development. The recursive nature of the system is reflected in the temporal sequence involved in the variables selected: 1950 lot prices are used to predict densities of development from 1950 to 1960, and 1960 lot and land prices are used to predict densities from 1960 to 1970. The ten-year time periods of the census data on densities of development undoubtedly extend beyond the effects of the land prices at the beginning of each decade. Therefore, the available land and lot price data for 1964 are also used, even though this temporally follows the 1960 to 1964 development. The possibility exists that densities of development could affect land prices as well, creating a situation involving simultaneous causation. In such a case, ordinary least-squares procedures for esti- 395 mating the parameterswould be inappropriate. Alternative models were considered, with the density of development variable (from either decade) included as a predictor of land prices. Two-stage least-squares procedures were used to estimate the parameters, with population, income and the population change variables considered as exogenous. In each case, the parameter values associated with the original three predictors of land prices were hardly changed from those obtained with the recursive model, while the parameter associated with density of development was insignificant. For this reason, only the results from the recursive model, obtained using ordinary least-squares regression, are reported here.12 EMPIRICALRESULTS The first set of regressions involved tests of the hypothesis that land values would be directly affected by levels of expectation and hence population change. In addition, population and income levels were also expected to have direct effects on land prices. The results of six regressions with alternative dependent variables as measures of land value are shown in Table 1. (All regressions involve fifty-one SMSAs. A significance level of 0.05 is used throughout this research.) These simple three-variable regression models account quite well for the variation in land values. In five of the six cases, the coefficients of determination (R2) were significant and ranged from 0.41 to 0.55. Only with FHA lot prices 12The results of the various alternative tests referred to in this section can be provided by the author to those who are interested. Land Economics 396 TABLE 1 LAND VALUE REGRESSIONS (Standard Errors in Parentheses) Dependent Variable Independent Variables Population Change (Percent) NAHB Land Price, 1960 NAHB Land Price, 1964 NAHB Lot Price, 1960 NAHB Lot Price, 1964 FHA Lot Price, 1964 FHA Lot Price, 1950 Population (Thousands) 25.49* (7.70) 47.71* (12.81) 4.60 (4.45) 10.03 (7.26) 9.16* (3.79) 1.23 (1.57) 0.67 (0.15) 1.32* (0.24) 0.27* (0.084) 0.52* (0.14) 0.19* (0.072) 0.085* (0.038) Constant R2 -152 0.47* -1426 0.55* Median Income (Dollars) 0.21 (0.27) 0.43 (0.45) 0.37* (0.15) 0.86* (0.25) 0.37* (0.13) -0.025 (0.093) 609 -1535 0.41* 0.53* 122 0.42* 972 0.11 *Significantlydifferentfromzero at the 0.05 level. in 1950 did the model fail to account for very much of the variation. Land values were positively related to population change, population and income, as was predicted. The only discrepancy was a very insignificant negative coefficient for income, again for 1950. Quite a few of the regression coefficients were significantly different from zero. Overall, the results lend considerable support to the hypotheses suggested earlier. The best results came in the prediction of NAHB land prices in 1960 and 1964. These variables were the most satisfactory measure of land values. Coefficients of determination of 0.47 and 0.55 mean that about half of the variation in these land prices across metropolitan areas was accounted for. The regression coefficients varied between the two regressions for 1960 and 1964 but give an idea of the strength of the relationships. A one percent increase in the rate of population growth produced a twenty-five to fifty dollar per acre in- crease in land prices across the fifty-one metropolitan areas. Each additional thousand in the population was associated with something on the order of a dollar increment in land values. A onedollar increase in median incomes produced a twenty- to forty-cent increase in land values. The coefficients for income were not significant and were subject to considerably more error.13 Roughly comparable relationships held with the four lot price variables. The coefficients tended to be much smaller for population change and population. Since the dependent variable was price per lot, not price per acre, and lots '3Schmid [1968, p. 51] found population to be significantly related to the percent appreciationin landprices(see note 10). Percentpopulationchangein the centralcity was also significant,but changein the urbanizedarea was not. This may have resultedfrom the problemsinvolvedin the use of urbanizedareasto measurepopulationchange,noted earlier.In addition, Schmid'sresultswereaffectedby multicollinearity. 397 Ottensmann: UrbanSprawl TABLE 2 DENSITY OF DEVELOPMENT REGRESSIONS (Standard Errors in Parentheses) Independent Variables Regression Land Value (Thousands) % Single-Family Development, 1960-70, with: NAHB Land Price, 1960 NAHB Land Price, 1964 NAHB Lot Price, 1960 NAHB Lot Price, 1964 FHA Lot Price, 1964 %Single-Family Development, 1950-60, with: FHA Lot Price, 1950 Constant R2 95.6 0.59* 94.7 0.56* 96.2 0.57* 93.2 0.57* 96.2 0.61* 109.9 0.28* Median Population Income Change Population (Percent) (Millions) (Thousands) -1.45* (0.64) -0.51 (0.39) -2.01 (1.19) -1.21 (0.73) -3.66* (1.26) -0.22* (0.080) -0.24* (0.085) -0.27* (0.079) -0.25* (0.080) 0.26* (0.075) -1.58 (0.81) -1.88* (0.89) -2.05* (0.77) -1.93* (0.81) -1.94* (0.70) -3.55* (1.27) -3.60* (1.32) -2.97 (1.37) -2.73 (1.43) -2.39 (1.31) -8.68* (3.23) -0.043 (0.037) -0.39 (0.88) -4.05 (2.05) *Significantlydifferentfromzero at the 0.05 level. tend to be smaller than an acre, the lesser values of the regression coefficients were understandable. Income tended to have a greater impact on lot prices. Higher median incomes may have led to greater lot sizes in some metropolitan areas, accounting for higher lot prices and a stronger relationship. The second set of regressions tested the hypothesis that the density of residential development would vary directly with land value, population change and population (Table 2). Since the percentage of new housing units constructed during a decade as single-family dwellings is being used as the surrogate for density, the expected direction of all relationships is negative. Six estimates are reported. Attempts were made to predict percent single-family development during the 1960-1970 decade using each of the 1960 and 1964 land price and lot price variables. The 1950 FHA lot price variable was used, with the 1950-1960 development as the dependent variable. The regression model was very effective in accounting for variations in the percentage of single-family development across the metropolitan areas in the sample. The coefficient of determination was significant in all of the five predictions of development density during the period from 1960 to 1970. The model was slightly less successful for the preceding decade. Land values, population change, population and income are all inversely related to the percentage of single-family development in each of the equations. The first three relationships were predicted, while the effect of income had been uncertain. Increases in land values caused de- 398 dines in the development of single-family housing. During the 1960-1970 decade, a one-thousand-dollar rise in land values produced a one-half to three and one-half percent decline in the percentage of development in single-family units. Two of the five regression coefficients were significantly different from zero. (The wide variation in the five tests was not unexpected given the great differences in the five measures of land values, including prices both per acre and per lot.) The rate of population change had a significant (five out of five) impact on the density of new development; a one percent increase in the growth rate produced about a quarter of a percent decrease in the level of single-family development. Likewise, a million in population was associated with a two percent decline in the dependent variable. Finally, median income had a sometimes significant negative effect, with a thousand dollars in income associated with about a three percent lower level of single-family housing. This suggests, perhaps, that the effect of income in raising land values (measured imperfectly here) may be more important than any increase in the demand for space by the higher-income households. The one model for the prediction of the percentage of development in singlefamily units from 1950 to 1960 yields generally comparable results. The effect of FHA lot prices in 1950 was dramatic (and significant), with a one-thousanddollar increase in lot prices associated with nearly a nine percent decline in the level of single-family development. Population change and population have somewhat smaller effects, while the effect of income is slightly greater. None of these coefficients was significant, however. The results of these empirical tests confirm the original hypotheses: The Land Economics rate of population change positively affects the levels of land values, while these two variables in turn clearly and positively affect the densities of residential development, as measured by the percentage of development in singlefamily units. The models account for approximately half of the variation in the dependent variables in all but a few of the tests. CONCLUSION The success of the land value model helped confirm the theoretical account of the role and importance of landowner expectations in the residential development process. Other alternative explanations of the levels of land values have been provided, however; the derived demand model developed and tested by Witte [1975] is one of the best examples. She has achieved higher coefficients of determination but only at the expense of considering a greater number of independent variables. The simple, straightforward model tested here, with but three independent variables, must be considered as a valid alternative. The success in predicting density of development provides far more encouragement for the theoretical account of the residential development process presented above. Both land values and landowner expectations clearly influence the percentage of development in single-family units, as predicted. Neutze [1968, pp. 93-102] examined the influences of land prices, city size and growth on apartment development, but his results were not conclusive. The Harrison and Kain predictions of density [1974, pp. 66-67] used city size as a surrogate for land rents. Their examination of densi- Ottensmann: Urban Sprawl ties over an extended period made the use of land rents impossible in their research. The present model effectively predicts the density of new residential development, relating it to both land values and landowner expectations within the context of a theoretical account of the peripheral growth process. The first hypothesis-that levels of landowner expectations directly affect the quantity of land withheld and hence urban sprawl-was not tested. The conceptual problems involved in the measurement of sprawl are very great, and appropriate data are not available in comparable forms across metropolitan areas. The description of the nature of peripheral urban development given in this paper highlights the role of landowner expectations concerning future growth in shaping the pattern of future development. Relatively little is known about the way in which these expectations develop or the correspondence between these expectations and reality. Schmid [1968] has pointed out that landowner expectations might well diverge from a realistic appraisalof future urban growth possibilities, and further observed that "there is no a priori reason to expect that a bad guess about the future will not continue for a number of years, with resulting higher monopoly-like prices to many consumers" [1968, p. 42]. Such a bad guess would also be reflected in the entire pattern of urban development, with more land being withheld-and more sprawl-than would actually be warranted. Especially at the present time, when many urban areas seem to be passing from periods of rapid expansion into an era of much slower growth, possible lags in landowner expectations could present a serious problem. This paper has provided a point of departure 399 for the investigation of such problems by providing an explanation of the nature of the development process incorporating the important elements of landowner expectations, urban sprawl, land values and the density of development. References Alonso, William. 1964. Location and Land Use. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Archer, R. W. 1973. "Land Speculation and Scattered Development: Failures in UrbanFringe Land Market." Urban Studies 10 (Oct.): 367-72. Bahl, Roy W. 1968. "The Role of the Property Tax as a Constraint to Urban Sprawl." Journal of Regional Science 8 (Aug.): 199-207. Boyce, Ronald R. 1963. "Myth Versus Reality in Urban Planning." Land Economics 39 (Aug.): 241-51. Clawson, Marion. 1962. "Urban Sprawl and Speculation in Suburban Land." Land Economics 38 (May): 99-111. 1971. Suburban Land Conversion in the United States. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc. Harrison, David Jr., and Kain, John F. 1974. "Cumulative Urban Growth and Urban Density Functions." Journal of Urban Economics 1 (Feb.): 61-98. Harvey, Robert 0., and Clark, W. A. V. 1965. "The Nature and Economics of Urban Sprawl." Land Economics 41 (Feb.): 1-9. Kaiser, Edward J.; Massie, Ronald W.; Weiss, Shirley F.; and Smith, John E. 1968. "Predicting the Behavior of Predevelopment Landowners on the Urban Fringe." Journal of the American Institute of Planners 34 (Sept.): 328-33. Lessinger, Jack. 1962. "The Case for Scatteration: Some Reflections on the National Capital Region Plan for the Year 2000." Journal of the American Institute of Planners 28 (Aug.): 159-69. Maisel, Sherman J. 1963. "Background Information on Costs of Land for Single-Family Housing." In Report on Housing in California, Appendix. Governor's Advisory Commission on Housing Problems, Sacramento. . 1964. "Price Movements of Building Sites in the United States: A Comparison Land Economics 400 Among Metropolitan Areas." Regional Science Association Papers 12: 47-60. Mills, Edwin S. 1969. "The Value of Urban Land." In The Quality of the Urban Environment, ed. Harvey S. Perloff. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc. . 1972. Studies in the Structure of the Urban Economy. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc. Mittelbach, Frank G., and Cunningham, Phoebe. 1964. "Some Elements in Interregional Differences in Urban Land Values." Reprint no. 31, Real Estate Research Program, University of California, Los Angeles. Muth, Richard F. 1969. Cities and Housing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. . 1971. "The Derived Demand for Urban Residential Land." Urban Studies 8 (Oct.): 243-54. Neutze, Max. 1968. The Suburban Apartment Boom. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc. 1970. "The Price of Land for Urban Economic Record 46 Development." (Sept.): 313-28. Ohls, James C., and Pines, David. 1975. "Discontinuous Urban Development and Economic Efficiency." Land Economics 51 (Aug.): 224-34. Real Estate Research Corporation. 1974. The Costs of Sprawl: Literature Review and Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Sargent, Charles S. 1976. "Land Speculation and Urban Morphology." In Urban Policymaking and Metropolitan Dynamics, ed. John S. Adams. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Publishing Company. Schafer, Robert. 1974. The Suburbanization of Multifamily Housing. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, D. C. Health and Company. Schmid, A. Allan. 1968. Converting Land from Rural to Urban Uses. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc. U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1953. County and City Data Book, 1952 (A Statistical Abstract Supplement). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. . 1962. County and City Data Book, 1962 (A Statistical Abstract Supplement). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. . 1963. Census of Housing: 1960. Vol. 2, Metropolitan Housing. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. . 1973a. Census of Housing: 1970. Metropolitan Housing Characteristics. Final Reports HC(2)-2 to HC(2)-244. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. . 1973b. County and City Data Book, 1972 (A Statistical Abstract Supplement). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Witte, Ann Dryden. 1975. "The Determination of Interurban Residential Site Price Differences: A Derived Demand Model with Empirical Testing." Journal of Regional Science 15 (Dec.): 351-64.