Antidumping

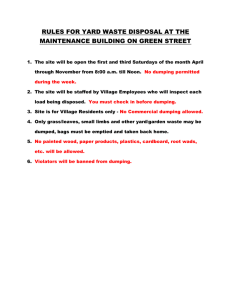

advertisement