Development Discussion Papers Central America Project Series Harvard Institute for International Development

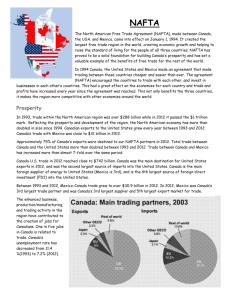

advertisement