Chapter 7 First version: December 9, 2002

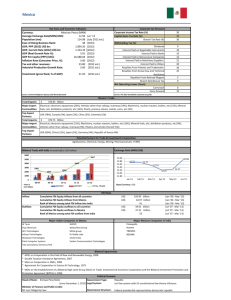

advertisement