Tilburg University Who is Turkish American? Leri, Alice

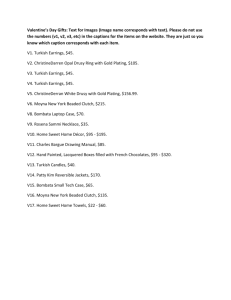

advertisement