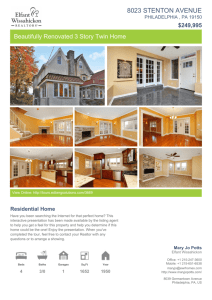

(1959) (1947) (1949)

advertisement