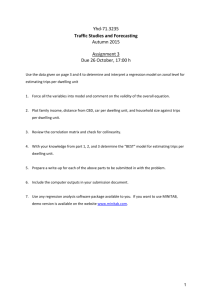

JUN 8 1961 L.I

advertisement