W T O

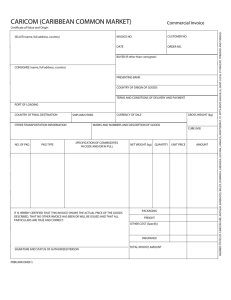

advertisement