Q )

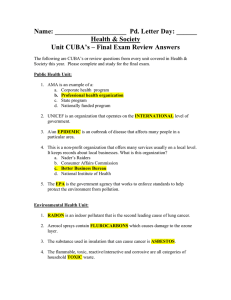

advertisement