RESPONSE PLANT CLOSINGS J. (1974)

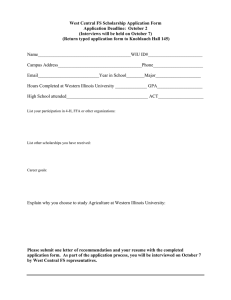

advertisement