DEVELOPMENTS AND ISSUES IN THE DOHA WORK PROGRAMME P

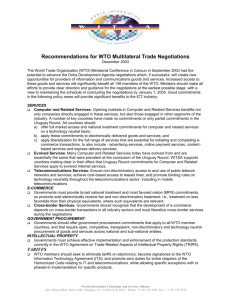

advertisement