Document 10565726

advertisement

The Learner-Centered

Paradigm of

Education

Sunnie Lee Watson

Charles M. Reigeluth

Contributing Editor

This article, the tlmd in d series of fOUl Instdllllll'llts,

begins hy diSCUSSing the l1el,eI for 1',ll,ldiglll ch,1Ilge ill

eelucJtion dnd for ,1 critiC11 svstl'ms aplllo,lCh 10

p"r,ldigm ch,mge, ,'ml ex,lmiI1l's currl'nt progress

toward pclrdCligm change. Then it explores wh,lt d

Il'JrIll'r-centcred, Informat ion-Agc cclul ,1 tion,,1 syslem

shou Id 1)(' Ii kl', incl uel ing I he AI l/\ Icwncr-celll ('rel I

psychologic,ll IJrinciples, the Ndlion,ll l~l".,l'<1rlh

Council's findings on how l'l'ollle' IC'Hll, Ill(' work 01

McCombs ,mdcolle,lgues on Ic,lrnCr-Cl'nl('r('d ..,c hool..,

,lnd cl,1ssrooms, perslHldlizccl Ic,lIning, cliIJl'rentidlc(1

in<,truction, ,'nd br,lin-Ilascd instrul lion. Fllldlly, onc

pos<,iblc vision of ,1 ledrlll'r-lCnlered school i..,

dcscri Iwei.

Introduction

The dissatisfaction with ,md loss of trust in schools tll,l[

we are experiencing these d,lYS ,lre Cll',lr h,lIlm,ll"ks of

thl' need for change in our school svslc'ms. The strong

push for a learner-centered p,lr,leligm oj illslruction in

today's schools reflects our socil'ty's ch,mging educa­

tional needs. We educators must help our schools to

move into the new learner-centered par,Hligm 01

instruction that better meets the needs of individu,ll

le,lrners, of their work pl'lces ,md communities, ,md 01

society in general. It is ,lisa import,lllt that we edUc,ltors

help the transformation occur ,1S effectively and p,lin­

lessly as possible. This article begins by addressing the

need for transforming our education,ll systems to the

Sunnie lee Watson is As<,ociate Instruclor, Instructlon,ll

Systems Tl>chnology DepJrtment ancl Eeluc,ltional Le,llb..,hip

and Policy Stuelies, in the School of EelUc,ltion ,It Indi'lila

Universily, Bloomington, Ineli,ln'l le-m'ltl: suklce(n'ineli,1n,1.

eelu). Charles M. Reigeluth is Professor, Instructional Systems

Technology DepJrtment, in the School of Education ,It

Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Ie-mail: reigelut(o

indiana.eduL

42

Paradigm Change in Public Education

This is the third in a series of four articles on paradigm

change in education. The first (May-June 2008) addressed

the need for paradigm change in education and described

the AECT FutureMinds Initiative for helping state

departments of education to engage their school districts in

this kind of change. The second (July-August) described

the School System Transformation (SST) Protocol that

captures the current state of knowledge about how states

can help their school districts to engage in paradigm

change. This article describes the nature of the learner­

centered paradigm of education, and it addresses why this

paradigm is needed. The final article (November­

December) will explore a full range of roles that technology

might play In this new paradigm of education.

learner-cl'ntered paradigm. Then it describes the nature

of thl' lc"lr1ler-centerecl paradigm.

The Need for Change and the (Critical)

Systems Approach to Educational Change

Information-Age vs. Industrial-Age Education. Where­

socidy has shifted from the Industrial Age into what

m,my c,lll the 'Information Age' (Toffler, 1984;

Rpigl'luth, !LJLJ4; Senge, Clmbron-McCabe, Lucas,

Smilh, Dutton, & Kleiner, 20(0), current schools were

eS[dill islwel to lit the needs of an Industrial-Age society

(sec 1,111lp 1J. This l'lCtory-moelel, Industrial-Age school

system hds highly compartmentalized learning into

sullied ,1Ie,lS, ,lild students arc expected to learn the

S,lnll' content in the same ,lmount of time (Reigeluth,

I CJCJ4 J. The current Sl hool system strives for standard i­

z,ltion ,md was not designed to meet individual

ledrrlers' Ileeds. Rathpr it W,lS designed to sort students

inlo IdlJOrers ,md m,lilagers (sec Table 2), and students

are forced to move on with the rest of the class regard­

less of whether or not they hJve learned the material,

,mel thus Ill,lily students ,lCculTlulate learning deficits

,mel eventu,llly drop out.

,1S

The (Critical) Systems Approach to Educational

Change. Systemic educational trJllsforlTlation strives to

change the school system to a learner-centered

pdr,lcligm that will meet ,111 learners' educationJI needs.

It is concerned with the creation of a completely new

system, r,lther than a mere retooling of the current

system. It entails a paradigm shift as opposed to

piecemeal change. Repeated calls for massive reform of

current educational and training practices have

consistently been published over the last several

e1ecades. This has resulted in an increasing recognition

of the need for systemic transformation in education, as

Ilumerous piecemeal approaches to education reform

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY/September-October 2008

Table 1. Key markers of Industrial vs. Information Age

education (Reigeluth, 1994).

II

Information Age

I

Team

Orga nization -------J

Industrial Age

Bureaucratic

Organization

Autocratic leadership

Centralized control

Adversarial relationships

Standardization (mass

production, mass marketing,

mass communications, etc)

Compliance

Conformity

One-way communications

Compartmentalization (division

of labor)

Shared leade,r,shi P

Autonomy,

accountability

Cooperative

relationships

I

II

I

I

Customization

(customized

prod uctlon, customized

marketing. customized

communications, etc)

Initiative

Diversity

Networking

Holism (Integration of

tasks)

J

----------

Table 2. Key features: Sorting vs. learning.

Sorting Based

Paradigm of

Education

!Learning Based!

I

Paradigm of

I

Time-based

I

L

Education~

Attainment-based

Group-based

Person-based

Teacher-based

Resource-based

Norm-based assessment

Criterion-based

assessment

I

have been implemented ,lnd h,)V(' fai!l,d to c,lgnificanlly

improve the stale of education. Syst('nlic Ir,lIlsforlll,1lion

seeks 10 shift from ,1 par'ldigm in which lime is held

constant, thereby forcing achievement to V,lIV, to one

designed specifically to meet the needs o! Informatioll­

Age learners and their communities by ,lliowing

students the time th;lt each needs to leach profici('llCy.

Systemic educltion,ll ch'lIlge dr,lws Iw,lVily from Ill('

work on critical systems theory (CSTI 1F'loo(1 ,<:' Jackson,

1q91; Jackson, 1qq 1a, 1()tIl b; Watson, Watson, ,<:,

Reigeluth, 2(08). CST has its roots in c,yc,teills theory,

which was established in the mid-twentieth cenlury hy

a multi-disciplinary group of researchers who sh,lred

the view that science had become inue,lsingl\

reductionist and the various discil)lines isol,l!eCI. While

the term system has been defined in ,1 V,lrielv of wavs

by different systems scholars, the centr,ll notion of

systems theory is the importance of rc'lationships ,lmollg

elements comprising a whole.

CST draws heavi lyon the phi losophy of H,lbermas

(1973, 1984, 19B7l. The critical systems approach to

social systems is of pZlIticular importance when

ccJllsidering svstems wherein inequality of power exists

in rel,ltion to opportunity, authority, and control. In the

1980s, CST came to the forefront (Jackson, 1985;

Ulrich, 19831, influencing systems theory into the

1qqos (Flood & l'lCkson, 1991; Jackson, 199101, 1991b).

Liber,1ting Svsteills Theory uses a post-positivist

appro,lch to analyze social conditions in order to

liller,lle the oppressed, while also seeking to liberate

systeills theory from tendencies such as self-imposed

insularity, cases of internal localized subjugations in

d iscou rse, ,1ml liberation of system concepts from the

in,ldeclu,lCies of objectivist and subjectivist approaches

irloo(l, 1q(J(lI. Jackson (1 q91 b) explains that CST

embraces tive key commitments:

• critical awareness of examining values entering

inlo aClual systeills design;

• soci,ll ,lW,1IeIWSS o! r('cognition in pressures

!e;ld i ng 10 populariz,ltion of certa i n systems

theories and methodologies;

• dedic,ltion to human emancipation tor full

developillent of all human potential;

• i nlormed usc' of systems methodologies; and

• informed dev('\opment ot all alternative positions

ami ditferent Ilwordical systems approaches.

I)an,llhy (1 qq 1l ,1nd Sc'nge <'t <11. (2000) apply

c,ystelllS tlwmy to the design of educational systems.

l)an,llhy (19<J2) suggests examining systems through

threc Icnses: ,1 "still picture lC'ns" to appreciate the

comlJ(lIWnlc, comprising the system <lnd their

l-el,ltiomhi!)s; a "motion picturC' lells" to recognize the

procc'sses ,1I1e1 dYl1,1mics of the systC'lll; ,11ld a "bird's

C'ye view Icm" to 1)(' ,1W~1rC of the relatiollships

\)('Iw('('n the svstem ,1nd its peers and suprasystems.

Seng(' ('{ ,1/. (20(H)) 'lpplies systems theory specifically

to mg,lIliz,ltion,11 k"1rning, st,lting that the organization

C<1I1 1<'Mn to work ,1S ,1n interrelated, hoi istic learning

comillunilv, r,llher th,ln functioning ,1S isolated

dep,lrtlllC'nl s.

Current Progress of Systemic Change in Education.

While svslemic education,ll transformation is a rela­

lively new moveillent in school change, there are

currC'ntly v,lrious ,lttempts to advance knowledge about

it. Ex,1Il1ples include: The Cuicbnce System for Trans­

Imming r:duc,ltion (Jenlink, Reigeluth, Carr, & Nelson,

I Q%,199Bl, Duffy's Step-Up-To-Excellence (2002),

Schhhty's II 9Q7, 2(02) guidelines for leadership in

school rdorm, Hamiller and Ch,lmpy's (1993, 2(03)

Process Reengineering, and Ackoff's (1981) Ideal ized

SystC'llls Design.

There are ,llso stories of school districts making

funci,lnlCntal changes in schools based on the

,1pp!ication of systemic ch;lnge ideas. One of the best

practices of systemic transformation is in the Chugach

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGYISeptember-October 2008

43

School District (CSD). The students in CSD arc

scattered throughout 22 ,000 square miles of remote

area in South-central Alaskel. The district was in crisis

twelve years ago due to low student reading ability,

and the school district committed to a systemic

transformation effort. Battino and Clem i20061 explain

how the CSD's usc of individual learning plans, student

assessment binders, student leaming profiles, and

student life-skills portfolios support and document

progress tOWelrd mastery in ell I stelndards for each

learner. The students arc given the flexibility to achieve

levels at their own p,lCe, not having to wait for the rest

of the class or being pushed into le,lrning hevond their

developmental level. Gr,Hlu,ltion stemclards exceed

state requirements ,1S students arc allowccl extrJ time to

,lChieve thJt level if necessary, hut musl meet the high

rigor of the gr,lcluation levl'l. Stuclent accoillplishnwnt

in academic perform'lnce skyrocketed ,1S ,1 result of

these systemic ch'lnges (f1,lttino c'\ C1elll, 2[)[)()!.

CJine (2[)06) ,llso found strong I)ositive changes

through system ic ecluCc1t ion,11 ch'lnge in extensive

engagement on ,1 project c,llied "Le'lrning to Le,lrn" in

AdelJide, South Australia, ,In initiative of thc South

Australi,1n Governmen1 th,lt covered d network of over

170 eduCcltion,11 sites. ~rolll l)I"eschool to 121h grJde,

brZl in-be1sl>d, lea rner-Cl'ntered k',1 rn ing envi ronillents

were combined with ,1 Icllger set of Svstl'lllic changes,

leading to both betler student ,Hhievement 'lild

signifiCclnt ch'lnges in the cullure ,md olwr,ltion of the

systelll itself.

Imagining Learner-Centered Schools

Giwn the necd for 1),Hadigm ch'lngc ill school

systems, wh,lt should our schools look like in the

future? The ch,1I1ges in society ,1S ,1 whole reflect J IWl'd

for educJtion to focus on 1c>,lIning I'dther th,1n sorting

students (McComhs &: Whisler,1 qq7; Reigeluth, 1997;

Senge et ell., 200[); Tofller, 1qg4!, A I'lrge ,lmount of

reseclrch has becn conducted to ,1dv,1nce our

understanding of learning anel how the eduCcltional

system can be lhcmged to better support it. There is

sol id rese,1rch e1bout 1)1",1 in-hased le,Hn ing, le,1I"ner­

centered instruction, ,1nd the Ilsychological principles

of leJrners that provide educ,ltl)l"s with a v,1luable

fra mework for t he Informc1l ion-Age peHclCl igm of

education (AiC'xander (:. Murphy, 1993; Br,msford,

Brown, &: Cocking, I CJ99; H,1nnUIll c'\ McCombs, 200B;

Lambert c'\ McColllbs, 199B; McCombs ,,\ Whisler,

1997).

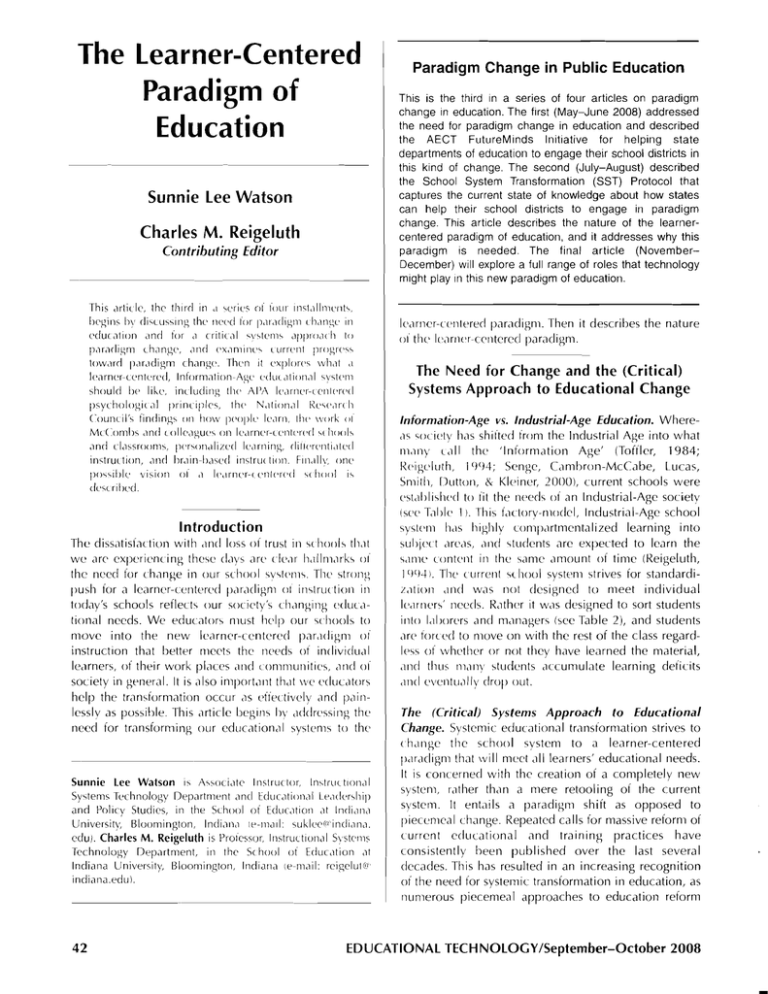

research to identify learner-centered psychological

principles based on educJtional research (American

Psychological Association's Board of Educational

Affairs, 1997; Lambelt & McCombs, 1(98). The report

presents 12 principles Jnd provides the research

evidence thJt supports each principle. It categorizes the

psychological principles into four areas: (1) cognitive

and metacognitive, (2) motivationa I and affective, (3)

developmental and social, and (4) individual difference

fJctors that influence learners Jnd learning (see Table

3).

National Research Council's "How People Learn."

Another important line of research was carried out

by the National Research Council to synthesize knowl­

edge about how people learn (Bransford et al., 1(99).

A two-vear study \Vas conducted to develop a synthesis

of new JpprOe1ches to instruction thJt "make it possible

for the mJjority of individuals to develop a deep

understanding of importJnt subject mJtter" (p. 6). Their

,lne1lvsis of ,1 wide range of reseJrch on leJrning

emph,lsizes the importJnce of customization Jnd

person,llization in instruction for each individual

learner, self-regulated learners tJking more control of

their own leJrning, and fJcilit,lting deep understJnding

of the subject m,ltter. They describe the crucial need for,

clnd characteristics of, leelrning environments thJt Jre

learner-centered Jncl reaming-community centered.

Learner-Centered Schools and Classrooms. McCombs

,md colleagues (f)aker, 1973; Lambert &: McComhs,

1998; McCombs & Whisler, 1997) Jlso address these

new needs alld ideJs for instruction thJt supports all

students. They identify two important fe,ltures of

lea rner-centered instruct ion:

... ,) focus on inclividu,ll lee1rl)crs (thcir heredity, experi­

enCl'S, perslJcctivcs, h'1Ckgrounds, talents, interests,

Cclp,Kitics, ,1nd nccds! I'lmll a focus on ICc1rning (thc

hest avail,lhlc knowledge ,lhout learning, how it

occurs, and what tt',1Ching pr,lctices ,HC most effective

in promoting thc highcst levels of motivJtion, Icarning,

ami ,1chlt'venwnt for all Icarnt'rs). (McCombs &

Whisler, I 997. p. 11)

APA Learner-Centered Psychological Principles. With

This twofold focus on leJrners Jnd learning informs

alld drives educationJI decision-making processes. In

leJrner-centered illstruction, learners are included in

these educational decision-making processes, the

diverse perspectives of individuals are respected, and

learners are treated as co-creators of the learning

process (McCombs & Whisler, 1(97).

significant reseJrch showing thJt instruction should be

learner-centered to meet aII students' needs, there have

been severJI efforts to synthesize the knowledge on

learner-centered instruction. First, the American

Psychological Association conducted wide-ranging

Personalized Learning. Pel'sonalized Learning is part of

the learner-centered approach to instruction, dedicated

to helping each child to engage in the learning process

in the most productive and meaningful way to optimize

44

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY/September-October 2008

Table 3. Learner-Centered Psychological Principles (American Psychological Association's Board of Educational

Affairs, Center for Psychology in Schools and Education, 1997).

APA Learner-Centered Psychological Principles

Nature of the learning process.

The learning of complex subject matter is most effective when it is an intentional process

of constructing meaning from information and experience.

Goals of the learning process

The successful learner, over time and with support and instructional guidance, can create

meaningful. coherent representations of knowledge.

Construction of knowledge.

The successful learner can link new information with existing knowledge In meaningful

ways.

Strategic thinking.

The successful learner can create and use a repertoire of thinking and reasoning

strategies to achieve complex learning goals.

Thinking about thinking.

Higher-order strategies for selecting and monitoring mental operations facilitate creative

and critical thinking.

Context of learning.

Learning is influenced by enVIronmental factors. including culture. technology, and

instructional practices.

Cognitive and

Metacognitive Factors

Motivational and

Affective Factors

I Oe'e'opmeo',' aod

Motivational and emotional influences on learning.

What and how much IS learned is influenced by the learner's motivation. Motivation to

learn, in turn, is influenced by the individual's emotional states, beliefs, interests and goals,

and habits of thinking

Intrinsic motivation to learn

The learner's creativity, higher-order thinking. and natural curiosity all contribute to

motivation to learn. Intrinsic motivalion is stimulated by tasks of optimal novelty and

difficulty, relevant to personal interests. and providing for personal choice and control.

Effects of motivation on effort.

Acquisition of complex knowledge and skills requires extended learner effort and guided

~ractice Without. learners' motivation to learn. the willingness to exert this effort is unlikely

Without coercion

I

Developmental influences on learning.

As individuals develop, there are different opportunities and constraints for learning.

Learning is most effective when differential development within and across physical,

intellectual, emotional, and social domains is taken into account.

Social influences on learning.

Learning IS influenced by social interactions. interpersonal relations, and communication

with others.

-----+--------------1

Individual

Individual differences In learning.

Differences Factors

Learners have different strategies. approaches. and capabilities for learning that are a

function of prior experience and heredity

Learning and diversity

Learning is most effective when differences in learners' linguistic, cultural, and social

backgrounds are taken into account.

Standards and assessment.

Setting appropriately high and challenging standards and assessing the learner as well as

learning progress-including diagnostic, process, and outcome assessment-are integral I

parts of the learning process.

Social Factors

.

L

each chi Id's learn ing and success. Personal ized Learn ing

was cultivated in the 1970s hy the National

Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP)

and the Learning Environments Consortium (LEO

Internationa I, and was adopted by the spec ia I

education movement. It is based upon a sol id

foundation of the NASSP's educational research

findings and reports as to how students learn most

successfully (Keefe, 2007; Keefe & Jenkins, 2002),

including a strong emphasis on parental involvement,

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY/September-October 2008

45

more teacher and student interaction, attention to

differences in personal learning styles, sm"ller class

sizes, choices in personal goals alld instruclional

methods, student ownership in setting goals ami

designing the learning process, and technology use

(Clarke, 2003). L.eaders in other lields, such as

busi nessma n Wayne Hodgi 1l5, have presentt>d the idea

that learning will soon become Ill'I'SClnalized, whel'e the

learner both activates and cOlltrols hel" 01 his OWIl

learning environment ([)uvdl, Hodgins, Rl'h,l~, c'Z:

Robson, 20(4).

Differentiated Instruction. The recenl IllOVl'ment in

differentiated instruction is ,1IS() ,l resl)()IlS<' to the Ile(>cl

for a le,'rning-focused (as opposl'dlo ,1 sorling-(ocuserll

approach to instruction dnd educalion in sc hoo!s.

Diffcrenti,lted instruction is dn dpplo,lCh Ihdl enahles

teachers 10 plan strategicdlly to meet tlw Iweds olewrv

student. II is rIL'eply groun(led in the prillc iplc' Ih,'l th(-r('

is diversity within ,lilY group 01 ledrl1el"5 ,'nd th,lt

te,lehers should ,ldiust studeilis' ledming ("peri('llces

accordingly (Tomlinson, j lJlJlJ, 200 I, 2()() ;1. This drdws

from lhe work 01 Vvgolsky 11 lm(»), ('51)('( idlly his "ZOIll'

of proximal ckvclopnll'nt" IZI'I)I, ,lIld Imlll d,ssrllDm

researchers. Rese,lrclll'rs fouml Ihdt With dillel"r'nlidll'rl

instruction students le"rtwrl more ,lIlrl 1(,11 IH'llel" dhoul

themselves ,1Ild the sullject ,1[ed heing studi('d

(Tomlinson, 2001 I. I::vid('IlCl' (urllwr ill(llC,ltl'S Ihdl

students ,lre more successful ,lIld Il]()tivdlc'd ill schools

if they IL'<lrll in W,lyS thdt dre responsive 10 Ih('il"

readiness levels IVygots~v, I cJIH)I, 1)('I"SI111,1I Inleresls,

,lnrl Ic"rlling l,ro(iles ICsiks/c'lltmihdlvi,

1 CJCJO;

Sternherg, TorI(, c'Z: CI"igorenko. I CJCJI\I. The gOdl 01

differerltiated inslructioll is to d(I(lress Ihl's(' thlee

characteristics for ('dch slllclc'lll ITOllllillS(ln. 2001,

20ml.

Brain Research and Brain-Based Instruction. Anolhc'r

area of Slurly thdt gives us dn ufldersl,lllding 01 h<l\\

people I(>arn is the work Oil Ilr,lin rl'sedr(11 which

describes how lhe IJrdin lUll( tions. Cline ,'nd

colleagues (1997, 200'), 200!JI provi(le ,1 usdul

summary Df work on how the h',lin funclions in the

process of le;Hning through IIw12 prine iples Df Ilr,lin­

based learning. 13rain-b,'sed le,lming hegills when

le,lrners are encouraged to dctively il11nwrse them­

selves in their world ,'nd their Ic'<lrning r'xIK'riences. In

a school or c1assrool11 where hr,'in-hdsed Ic,lmillg is

being practiced, the signific,lIlce of (Iiverse indivirlu;ll

learning styles is taken for granted Ily t('dchers and

arlministrators (Caine 0.: Caine, I CJCJ7!. In these cl"ss­

rooms amJ schools, learning is (acilit,'led for ('<lch

individual student's Ilurposes ami nwallillg, and the

concept of learn i ng is appro'lChed in ,1 cDl11pletely

different way from the curl"ent classroDms th,lt arc set

up for sorting ,md standardization.

46

An Illustration of the New Vision

What might a learner-centered school look like? An

illustration or synthesis of the new vision may prove

helpful.

Imagine that there are no grade levels for this school.

Inslead, e,Jeh of the students strives to master and

check off their attainments in a personal "inventory of

attainments" (Reigeluth, 1994) that details the individ­

ua I student's progress through the district's requ ired

and optional learning standards, kind of like merit

badges in Scouti ng. Each student has different levels of

progress in every attainment, according to his or her

illterests, (,1 lents, and pace. The student moves to the

flext tOI)ic ,1S SOOIl as she Dr he masters the current one.

Wh i Ie each student must reach mastery level before

movillg on, studellts also do Ilot need to wait for others

who are Ilol yl't at that level of learning. In essence,

1l0W, 11ll' schools hold time constant and student

learnillg is thereby forced to vary. In this new paradigm

Df the le,lrller-centered school, it is the pace (learning

time) that varies rather than student learning. All

siudeills work ,It their own maximum pace to reach

m,lstery ill each attainment. This individualized,

customized, alld self-paced learning process allows the

school district to realize high standards for its students.

The [("lelwr t"kes on a drastically different role in

the le,lrnillg proccss" She or he is a guide or facilitator

who works with the student for at least four years,

buildillg ,1 IOllg-term, caring relationship (Reigeluth,

11)1)41. The leacher's role is to help the student and

I),lreilis to decide UpOIl appropriate learning goals and

to help irbltify ,'lld facilitate the best way for the

studellt to achieve those goals-and for the parents to

SUI)Port their stuclent. Therefore, each student has a

persolldl learnillg plan in the form of a contract that is

joifltly (Ic'velopecl every two months by the student,

p,lrenls, illld teacher.

This system enhances motivation by placing greater

responsibility ,'nrl ownership on the students, and by

offeri ng trLl Iy eng,lgi ng, often collaborative work for

students (Schlechty, 20021. Teachers help students to

direct their own learnillg through the contract

rlevelDpnlC'nt process and through facilitating real­

world, independellt or small-group projects that focus

Oil developing the contracted attainments. Students

learn to set ,'ncl meet deadlines. The older the students

get, the more leadership and assisting of younger

stuclents they assume.

The commullity also works closely with schools, as

the inventory of attainments includes standards in

service learning, career development, character devel­

opment, interpersona I ski lis, emotional development,

technology skills, cultural awareness, and much more.

Tasks that are vehicles for such learning are authentic

tasks, often in real community environments that are

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY/September-October 2008

rich for learning (Reigeluth, 1994). Most learning is

interdisciplinary, drJwing from both specific and gen­

eral knowledge and interpersonJI Jncl decision-mJking

skills. Much of the focus is on developing deep under­

standings Jnd higher-order thinking skills.

TeJchers assess students' leJrning progress through

various methods, such JS computer-based assessment

embedded in simulations, observation of student

performJnces, Jnd JnJlvsis of student products of

various kinds. InsteJd of grJdes, stuelents receive

rJtings of "emerging," "developing," "proficient" (the

minimum required to pass), or "expen."

EJch teJcher hJS J cldre of students with whom she

or he works for severill vearS-,l eleveloprlwnt,ll st'lge

of their lives. The te,rellC'r works with 3-10 other

teJchers in J smJl1 le,lrning community ISI_CI in which

the leJrners Jre multi-'lged ,lnd gl't to know ('<reh other

well. Students get to choose which t(',lclwr thcy w,lnt

(stJting their first, second, ,1Ilel thir'd choicc), ,1nd

teJcher honuses Jre baseel on thc ,lmounl of <lel1lanel

for them. Each SLC hJS its own budget, haseel mJinh

on the number of students it h~lS, ,1ndm,lk<'s all its own

decisions Jbout hiring and firing 01 its St,l!!, including

its principJI (or leJd te,Kheri. E,reh SLC ,1lso h,lS ,1

school bOJrd made up of t(',relwrs ,lnel IJarcllts who ,lrc>

elected by thei I' peers.

While this illustration 01 a le,lI"l1l>I"-(Clltereei schoul is

bJsed on the various learner-centered ,lppro,rehes to

instruction reviewed (',1rlier ,1Ild the I,ltest (>dLIC,ltiorlal

research, this is just one u! m,lny possihle visions, ,md

these ideJs need revision, ,1S some ,lre likelv to vdry

from one community !o 'lnother, ,111<1 most rwed !unher

elJborJtion on detlils. Nonetheless, this I)ictur<> o! d

learner-center'ed p,lraeligm of schuoling coulel hell) us

to prevail over the industri'll-age 1),1ra<ligm of !('<lI"ning

and schools so th,lt we Cdn create ,1 Iwtter 1)I,ree for uur

children to leJrn.

Conclusion

Our society nl'eds 1c>,ltner-centered schouls th,lt

focus on leJrning rather than on sorting (McComlJs &

Whisler,1997; Reigeluth, 1997; Senge pI aI, 2000;

Toffler, 1984). New JpproJches to instruction and

education have increJsingly been advocated tu meet

the needs of all learner's, and ,1 large amount of

research has been conducted to ,Hlv,lnce our

understanding of leJtning and huw the ('ducltional

system can be changed to better SUIJPort it (Alexander

& Murphy, 1993; McCombs & Whisler, 1997;

Reigeluth, 1997; Senge el al., 2000J. Nevertheless,

transforming school culture and structure is not an easy

task.

Isolated reforms, typicJlly at the clJssroom Jnel

school levels, have been attempted over the pJst

several decades, and their impact on the school system

has been negligible. It has become cleJr that

trJnsforming the paradigm of schools is not a simple

job. Teachers, administrators, parents, policy-makers,

students, and all other stakeholder groups must work

together, as they CJnnot change such a complex

culture Jnd system alone. In order to transform our

schools to be truly learner-centered, a critical systems

apprmch to trJnsformJtion is essentia I.

The first article in this series (Reigeluth & Duffy,

20081 described the FutureMinds Jpproach for state

education departments to support this kind of change

in their school districts. The second article (Duffy &

Reigeluth, 2008b) described the School System

TransformJtion (SST) Protocol, J synthesis of current

knowledge Jbout how to help school districts use a

critical systems apprmch to transform themselves to

the learner-centered pJradigm of educJtion. Hopefully,

with stJte leJdership through FutureMinds, the critical

systems Jpprmch to educational change in the SST

Protocol, and the new knowledge about learner­

centered instruction, we will be Jble to create a better

pl,1Ce for our children to leJrn and grow. However, this

task will not he eJsy, One essentiJI ingredient for it to

succeed is the aVJil,lbility of powerful tools to help

teachers Jnd students in the leJrner-centered paradigm.

The fourth article in this series will Jddress this need. I I

References

;\LKOr!, R. I.. 11 'lB t I. Cleating thp corpor,ltp iulure. New York:

lohn \Vi Icy & Sons.

/\!<'x,llllier. P. A. '-, Murphy, P. K. (1993). The research base

tor APA\ le,lrllc'r-centcred psychological principJls. In

8. L. I\\C COIl1IJS IChair), Taking resparch on learning

Wlio(/slv: Im/llrc,ltions (or tpacher pduca!ion. Invited

svll1j1osiull1 at the Annual Meeting of the AmericJn

})<,ycho!ogilal Association. New Orlean<,.

AnwrlLln Psychological Association's Board of Educational

Aii,l i 1'<', Center for Psychology in Schools and Education.

(I ')'!71. Lealller-centered psychological principles; http://

\v\vw.ap'l.org/l'd/lcp2/lcp 14.html .

8ak(>r. F 119731. Organi7ational systems: Cenpral systems

appruaclw> to complex organizations. Homewood, IL: R. D.

Irwin.

Banathy, B. H. (1991). Systems design oi education: A

joullley to ((eate the iuture. Englewood Cliffs, Nj:

Educationa 1Technology Pub Iications.

Ban,lthy, B. H. (1992). A systems view oi education:

Concepts and prinLiples ior etTective practice. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Battino. W., & Clem, J. (2006). Systemic changes in the

Chugach School District. Tech Trends, 50(2), 51-52.

Bransford, L Brown, A., & Cocking, R. IEds.). (1999). Hmv

people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Caine, R. N. (2005). 12 brain/mind learning principles in

action: The iieldbook for making connections, teaching.

EDUCATIONAL TECH NOLOGY/September-October 2008

47

school districts. Sy.'tems I\esearch and Beha\'iora/ Sciel1ce,

and the hl/man brain. Thous,mel O'lks. CA: Corwin Press

Caine, R. N. (20061. Systeillic ch'lnges in public schools

through brZlin-b,lseelleZlrning. TcrhTrt'nc!.;.'(J121,32-C,3.

Caine, R. N., &: Cline, G. (1 997!. FC/l/Cdlion on Ihe t'c!ge o(

possibility. AlexJndrlJ, VA: Associ,ltion ior SUlwrvisio!l &

fJerson,llized ilwiling ,1Ild person'llized

I. DiM,lItino, J. (I,llkl', &: D. Wolk IEels.l,

teJching. In

Persona/i7C'(/ /eaming: f'rC'jJ,lIing higher !Joo/ ,'tuc!cnIS to

erl'dle thcir {ull/res. L'lnh'llll, Mi): SCell'l'CrcJW \'IC"S.

cxpcrienCl'. New York: H,l!lH'r 0.: Row.

,]f](/

\17 innoldlilP

11'1\'drcling /Je'dOrlJJdnCl' in

L,llllbert, 1\:. M., &. McCombs, B. IEels.i. (1998). flow student.;

/e,1I'n:

I\f'iorming

cc!u(,ltion.

school\

throu,gh

le,1I'ner-centered

DC: Aillerican Psychological

Washington,

McComhs, B" &: Whisler,

J.

(1997). The /eartJf'r-centeled class­

Dutiy, F. M., &: Rc'igclulh, C. M. I..!()()BI The school SVstl'lll

tr,lnsiollll,ltion ISSTI IJllllocol. [C/UI dlionel!

·+814 I, 41-4 1)

Rt'igl'luth,

In C

c:.

M. 119941. The imperative ior systemic change.

M,

Reigeluth &

R. ). G,lIiinkle rEels.), Systemic

c!ldnge in cc!ucdtion. Englewood C1ilis, N): EduGltional

IchcJO! \'Ystem.;. L'lnh'llll, MD: SC,lll'nmV l'rc",.

/c'clm%,pl,

Technology PulJlications.

C.

Reigl'luth,

M.

119lJ7i.

Education,ll

st,lrlcbrels:

To

stJnCI,Helizp Clr to customize le,lInlllg l I'hi Delld Kappdn,

DUV'll, f' .. Ilodgins, W., Rch'lk, D., ,\ Rol)',(Jll, R. 1..!()()41.

IJ"lllling OhjC'ltS "YIll\lo"iulll "IJC'ci,ll i',ue gLiI',1 eclitoll,ll.

/oumell 0/ [lllfldlfOnd/ ,\.lu//imcrlf,1 dlH! 1/I/JC'II!II'lhd, 1)141,

)31.

;"')1 ll, 202-20(1.

Rl'igc'luth,

C.

0.:

M.,

Dulty,

F.

M.

1200Hi. TI1('

AECT

Futurc'Mincls initiative: Tr'lnslOiming Anll'riccl\ school

sv"lcllls. hluc,llion,l/ 7('c!Jn%g}', cJ8'lJ, 4S-49.

Flooel, R. L. (I 'Jl)()i. LiIJI'I,lling w,lelll, Ihc'olv: Tmv,ml uitic,li

systems thinking. lIl/m,l/) l-!.ddliol1', cJ Jill, 4')-;-,.

Flood, R. L., 0.: lelcbon IV1. C. I I '!'! II.

I/[',II!\('

!Hohlt'l))

H,l!JelmelS, I II');-ll I/l('o!\ ,I/)c! 11I,l,li(I' II. ViCIII'i, TI,lll'.I.

f lelfwrlll,l'" l. (I 'Ji\4I, r!J(' Ihl'oll oi '(JlJ)fJJUnll ,J/iIC' ,Ietion:

I-!.ca,'o/) ,Inl/ Ihc rdllo/),lii/,l/ion o/,OC il'/I ',T. MI CHill\',

I. IllJ1\71. Ihl' I/II'()!I' o! «I/I/IJlIIIl/CdlfIC' dllion'

Lili'wmlcl ,/111/ ,'I',II'IIl: I Ililil/lIl'

()! !II/I<

11U1l,1/ Ic',),on IT.

J. (11)1)\1.

II !II,lnill ',10 101 /JlI,il1l 'Ie

I-!.C'l'll,pill"I'lill,p //l('

/( 'io/illion.

1\:1'1\' VOlk:

11.1(1)('r Busilll'c,s.

H,lllllllc'r, M.,

,,\: Ch,lllllw,

I. ,200 \1. 1-!.1'I'n,gin('I'ring

cOl/Jord/ion: 1\ !IIdni(",lo (or hu,iIlC'"

1/]('

Ic\'o/u/ion 11,t

H,lIJler Husilwc,s [s,c'nli,d, 1,llk. I'd. I. !\Ic'\\' Vwk: II.H[X'I

J)usinl'SS h"l'nti,ll".

H,lnnulll, VV. H., ,,\: McCoIllIJ',

f). I. !..!()(JBI, Enhdnc illg

IJlinciples. [(/u('llion,d /('( !Jn%,~I. cJ<'!' II, I ]2] .

c:.

(I'dc/H'rs,

/)(/OCljJd/S,

,JI]I/,u/H'lin/coc!('o/s.

S,ln

Fr,lnci,co: losse\,-f),ls,.

Sc'nge,

f),

ClllliJroll-McC11)(·,

N.,

LUCclS, 1.,

Smith,

13.,

(//.'I illii/H' t'il'!(/hook ICJI CI/UCdloIS, pd/rols, clncl ('v('ryooc

II'IW ld/('I dlloul Cc!ll1'd/ioo. Toronto: Currc'ncv.

Ilicll(hic,llly illllmlvl's sluclt'1l1 ,1C hievelllcnl. /OLfIll,d 01

[c!u(,lI/OOd/ PI)'c!w/ug\' ()Ol l I, 17 4-31l4.

TOllllillsoll,

c:.

Thl' ncc'd fw ,1 critic,ll ,1111 Jlc),lCh , Inlc'rtJ,lIlO!J,l! /oUln,)/ o(

Ncw York: 8,HllelIll.

The (!iill'II'oti,J!c(! c!,lssroom:

l\c'!JOo(/lI1g /0 the n('('c!s o{ ,)!! /c,Jr!wrs.

AIe'Xelnclri,l,

Curricululll

Assmi,llioll

tor

Supelvi'ioll

elml

[)evl' Iop III cn t.

TOIllIIINJIl, C. A. (2001)

io

miwI/-d/JiIJI\'

Ilo\\' to l/ilic'lcllticl/e ;l1Sttuetion

c!elss/()O{]]S

1~e,sOCi,ltion

lor

121ld

l'II.L

AIc'x,lndri,l,

Supc'rvisioll

,1Ild

Curriculum

[)('Vl' I01'1ll I'll t.

TOlllliIlSOIl,

c:.

A. 1201HJ. fu/{i/liog Ihc fJ/()mise o{ (Ile

l/iI'(c/('oti,llcI/

11 ')Wi I. Soci,li sv,lclll' theOl\ ,1Ilci [n,ll ticl':

I\'<I\'C.

A. 119')'!1.

VI~:

VA:

rlist,lnce Ic,lIning fOl 1()(1,1I\ youth I\'lth 1e',lIncH'cnterl'd

I,lcbon, M.

ior

Toillel, A. (I '!Il,-II. 7he thire/

McClithy, TI,1I1S. I. J)o,ton: He,ll on l'rc's,.

CO! por,H ion:

SI hlechly, 1'. C. 120021. \V()/king on Ihc Ivo/k 1\0 dllioo p!dO

SIC'IIlIJl'lg, R., Tmll, I)., ,,\: Crigorcllko, E. (1 '!91lL TC'elching

Tr,lnS.I. Boslllll: f)c,lIOll l're".

M., ,,\: Chellll!!Y,

,I ')1)71. Invcnting hcller slhoo!s: I\n delion

[)ullon, I., 0.: Kleiner, A. 120001. Sc!)()o/s Illdt /edll1: 1\ (iith

I)o"ton: 1)C',llon I'll'"".

H,llwrll1,l',

c:.

SI hll'chlv, I)

/ll,]n !iJl Cclucdlllm,l/ II'lcJlI!I. S,lIl Fr,lllcisco: lossey-BJss.

solving: lold/ ,\plclJJ' 1I111'!\C'fJl!on. '""C'II Vmk: \Ohll \Vill'l

,mel Son,.

re"po/l'il'C'

c/,lss/()om.

tE"lching.

Slrdtcgics

,)1](/

/\!exelndri'l, VA:

(oo/s

Associ,ltioll

{or

for

SUIJI'l'visiun ,lncl CurricLilulll Developillellt.

Ulrich, VV. (1 YHll. Criticd/ hl'Ulistics u( ,()(ia/ p/annlng: (~

(;C'l1el,lIS\"/I'nl', lOlli, US-lSI.

),lc\.;son, M. C. 11'!'!1,11. The origins ,lIlcll1dtWl' 01 critical ,vs­

Il'lllS thinking. Systcm, I'i<lclil C', cJI2 i, 1 ll-14').

IWI\, dfJproach 10 plactlCol/ philosophy. Bern, Swit7erlelnd:

H,lUpt.

jack,on, M. C. (] l)91 bi. Po,t-Illodl'rtlislll end lllnlelllpOl,lr\

systems thinking. In R. C. Flood & M. C. j'lckson IFrls.l,

Critic,l/ systems Ihinkin,g IPIJ. 2IF-\02I. New Vork: John

Wiley 0.: Sons.

Vvgotskv,

L. 11 ')[\6i.

Thought and /dngu,lge IA.

(1996). An expedition tm ch'lilge. !f'chTrcnl/', ,,)1111,21­

3O.

lenlink, P. M., Reigeluth, c:. M, CHI, A A, &: Nelson, L. M.

(19981. Guidelinl's ior i,lCilitating systeillic ch,1I1ge in

Kozulin,

Tr,lnS.I. ClllllJridge, MA: MIT Press (origim I work puhlished

19261.

WJtson, S. L., Watson. W.,

jenlink, IJ t'v'1., Reigl'lulh, C. M., Cm, A. A., ,,\: Nc'lson, L. M.

48

Kede, W" &. Jenkins, J. (2002). A srecial section on personal­

room anc! school. S,ln Fr,lncisco: Jossey-BJss.

Dufiy, F. M. 120()21. StC!J LiIJ To 1'\('('//('1]( C"

1Llrllllwr,

,20071. WhJt is personalizJtion? Phi Delta Kappan,

As'ociJtion.

CsikS/'entmih'llyi, M. (1 9')()1. r/mL r/J(' IJ\lc!J%g) o( ojJtim,l/

,1IJ!JrOdC!J to IJJcmeiging

J.

,sl)r31, 21 ;--223.

ized instruction. Phi De/ta Kappan. 83(6), 44lJ-448.

Curricu Ium Devel 0IJ!lwnt.

CI,Hke, ). (20031.

75131,217-233.

Keele,

&: Reigeluth, C. M. (2008).

SystC'llls design lor ch'lIlge in education Jnd training. In

j. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill.

Driscoll

(Ecls.),

J.

van Merrienhoer, & M. P.

Handbook o( resealch tCJ( educational

communicatio!J.\ and technology Urel ed.).

New York:

Routleclge/L'll\'rence Erihauill AssociJtes.

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY/September-October 2008