Document 10558451

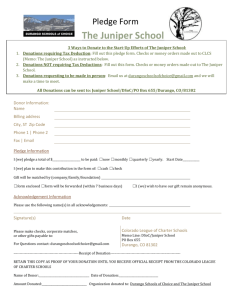

advertisement