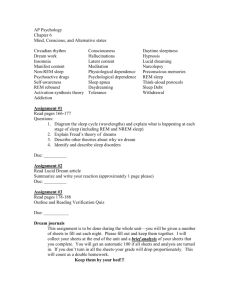

The effects of the tree-to-ground sleep transition in the

advertisement