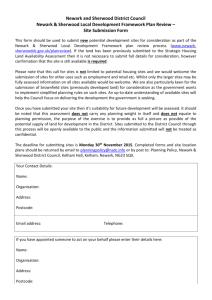

0D

advertisement