SPECIES FACT SHEET

advertisement

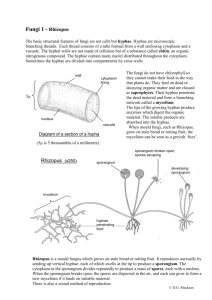

SPECIES FACT SHEET Common Name: Burnet’s skin lichen Scientific Name: Leptogium burnetiae C.W. Dodge Kingdom: Fungi Division: Ascomycota Class: Lecanoromycetes Order: Peltigerales Family: Collemataceae Nomenclature The nomenclature of this species has changed several times, leading to some confusion. C. W. Dodge named L. burnetiae in 1964. Sierk (1964) named North American specimens Leptogium hirsutum. In 1973, Jørgensen combined L. hirsutum into a variety of L. burnetiae writing, "L. hirsutum is so closely related to it and best treated as a variety of it [sic]." In 1997 he included only L. burnetiae (not L. burnetiae var. hirsutum) in a key to the hairy Leptogium species of the world, evidently deciding there was no discernable difference between the variety and the species in the strict sense. Technical Description: Thallus foliose, gelatinous when wet, medium-sized, 3-10 cm diameter, loosely adnate. Lobes 315 mm wide, with rounded margins. Lower surface pale to medium gray, smooth, with dense white (rarely pale brown) tomentum of long cylindrical hairs. Upper surface medium gray to bluish gray when dry, without definite wrinkles or ridges, matte to somewhat shiny, with or without small white hairs. Isidia originate as single, separate papillae on lobe surface, somewhat in from margin, then become cylindrical, simple to branched to dense and coralloid; also common in a single row along margins. Isidia matte and similar in color to thallus or slightly darker. Soredia absent. Medulla formed of densely packed hyphae, mostly lying parallel to the cortex and forming an almost solid hyphal mass in the center of the medulla. On the top and bottom of this mass, cyanobacteria are packed so tightly that their chains are not readily visible; instead they are visible as single cells (Stone 2010). Apothecia rare, laminal, stalked, 0.5-2.5 mm wide. Spores colorless, with crosswalls and longitudinal walls (muriform), 30-45 x 12-18 µm. Photobiont cyanobacterial (Nostoc). Chemistry: Spot test reactions negative. No secondary metabolites have been detected. (Brodo et al. 2001; Nash et al. 2004). Other descriptions and illustrations: Hinds and Hinds 2007, Jørgensen 1997, Nash et al. 2004, Stone 2010. Distinctive Characters: All Leptogium species are gelatinous lichens that swell and become jelly-like when wet. They are unstratified; the photobiont does not form a distinct layer within the thallus but is intermixed with fungal hyphae. Unlike Collema species, they do have an upper and lower cellular cortex, appearing as a surface layer of square to shortly rectangular cells. These features can best be seen with a compound microscope (see below). (1) blue-gray, foliose, gelatinous lichen with a densely white-hairy lower surface, (2) isidia that originate as single bumps on the surface, become cylindrical and then branched to coralloid with age, (3) medulla with tightly packed hyphae mostly parallel to and some perpendicular to the cortices. Similar Species Leptogium saturninum is most similar to L. burnetiae and can be very difficult to distinguish. In L. saturninum, surface coloration and texture appear to be connected. Isidia begin as a pattern of dark coloration near the edge of a lobe. The pattern originates as an even speckling of dark spots on the surface. As the thallus grows and widens this even dusting of dark particles becomes divided into patches, leaving bare, light-colored tracks through somewhat angular patches of dark-colored fine particles. With age, these dark areas begin to become rough and isidia erupt out of the thallus surface, destroying the cortex and forming patches of granular isidia which then become dense dark piles of granular isidia. (Stone 2010). In L. burnetiae, isidia originate as single, separate papillae on lobe surface, somewhat in from margin, then become cylindrical, simple to branched to dense and coralloid; also common in a single row along margins. Isidia similar in color to thallus or slightly darker. The structure of the medulla, seen in cross section, is also a distinguishing character. To clearly see the difference in medulla type, extremely thin sections are essential. If the sections are too thick, multiple layers of hyphae obscure the medullar structure. In L. saturninum, the medulla is formed of hyphae Perpendicular to and parallel to the upper and lower cortices, separated by spaces so the whole medulla looks airy and open. Within this open framework, chains of cyanobacteria lie in curves. Thalli of L. saturninum are variable in thickness from 100 to 300 µm, but the same structure is found in all. The amount of space between hyphae does vary from nearly touching to quite widely spaced, but the typical medulla is quite open-looking. In contrast, the medulla of L. burnetiae is formed of densely packed hyphae, mostly lying parallel to the cortex and forming an almost solid mass of fungal strands in the center of the medulla. Above and below this mass, cyanobacteria are packed so tightly that their chains are not readily visible; instead they are visible as single cells. Thalli of L. burnetiae seem quite variable in overall thickness and thickness of the central hyphal strand mass, but the pattern of a dense central-medullar mass with dense algae above and below remains consistent. Leptogium pseudofurfuraceum has a white-tomentose lower surface and cylindrical isidia. However, unlike L. burnetiae, it has a finely wrinkled upper surface, and a reddish-brown to brown-gray color. The dark brown to black, shiny isidia have a distinct dimple at the tip. Collema species are also dark-colored gelatinous lichens, but they lack an upper and lower cortex. This can be observed with a wet mount of a cross-section of the thallus through a compound microscope; see illustrations on page 15 in Brodo et al. (2001). In addition, Collema species are rarely hairy. Leptochidium albociliatum may have a white-hairy lower surface, but can be distinguished by short, stiff, clear, marginal hairs that are usually abundant and conspicuous with a hand lens. Fact Sheet for Leptogium burnetiae 2 Life History: L. burnetiae is often sterile, producing apothecia only occasionally. However, it reproduces asexually through abundant isidia, which are usually present year-round. Isidia are heavy propagules, therefore dispersal is limited. Range, Distribution, and Abundance: Globally, this species is widespread in the montane tropics, extending into warm temperate regions of Asia, Africa, Europe and North America (Nash et al. 2004). In the Pacific Northwest, it occurs in Washington, British Columbia and Alaska. It has been verified from only one location in Washington: in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (Björk 10428). Two specimens similar to L. burnetiae but with different structure of the medulla have been found in Oregon. One is at Saddle Mountain State Park (Derr 883) and the other in Jackson County on Crowfoot Creek (Medford District BLM, Callagan 1054). Habitat: This species is found on tree bark and on mossy rocks. In the Columbia River Gorge it occurs on Quercus garryana bark in a ponderosa pine/ garry oak/ arrowleaf balsamroot plant association at low elevations (100 and 400 feet). In Alaska, it is known from the Tongass National Forest at low-elevation sites (≤ 250 feet), where it occurs on Alnus sinuata, Picea sitchensis, Salix sp., and Populus trichocarpa (U.S. Department of Agriculture (no date). Threats: For this cyanolichen, shade and air moisture are an important part of the habitat, so any change in forest density or shading could degrade the habitat. The primary threat to this species is forest management activities that remove host trees or change the moisture regime. Timber harvest projects that remove or damage oaks, cottonwoods, and other hardwoods, especially in riparian areas, may directly threaten populations or reduce habitat (D. Stone, personal observation). Conservation considerations: Protect the known site and the two possible sites. Known populations can be protected by restricting removal of host trees and nearby habitat, preserving the light and moisture regime. Search riparian areas on Federal lands for more populations. Continue to protect riparian corridors, with large enough buffers to maintain humidity regimes. Conservation rankings: Global: G3G5. National: not ranked. ORBIC: S1. WNHP: not ranked. Preparers: Erika Wittmann & Jeanne Ponzetti Date completed: 9/18/2006 Revised: Daphne Stone 2012, February 2012 References Brodo, I., Sylvia Sharnoff, and Stephen Sharnoff. 2001. Lichens of North America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 795 pp. Fact Sheet for Leptogium burnetiae 3 Goward, T., B. McCune, and D. Meidinger. 1994. The Lichens of British Columbia: Illustrated Keys. Part 1 – Foliose and Squamulose Species. Special Report Series 8, British Columbia Ministry of Forests Research Program. Victoria, B.C.: Crown Publications. 181 pp. Hinds, J. W. and P. L. Hinds. 2007. The Macrolichens of New England. New York Botanical Garden Press, NY. Jørgensen, P.M. 1997. Further notes on hairy Leptogium species. Symb. Bot. Ups. 32: 1. McCune, B and L. Geiser. 2009. Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. 386 p. Nash, T.H.III, B.D. Ryan, P. Diederich, C. Gries, F. Bungartz, editors. 2004. Lichen flora of the greater Sonoran Desert region: volume II. Tempe, AZ: Lichens Unlimited & Arizona State University. 742 p. Sierk, H.A. 1964. The genus Leptogium in North America north of Mexico. The Bryologist 67(3): 245-317. Stone, D. 2010. A Search for Leptogium burnetiae C. W. Dodge in the Pacific Northwest. Interagency Special Status/Sensitive Species Program website, http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/sfpnw/issssp/ Last visited 21 Feb 2012. USDA Forest Service. no date. National Lichens and Air Quality Database and Clearinghouse. http://gis.nacse.org/lichenair/index.php?page=query&type=plot Last visited 24 February 2012. Fact Sheet for Leptogium burnetiae 4 Fig. 1. Thin cross-sections of Leptogium burnetiae, showing a medulla formed of tightly packed hyphae many of which are parallel to the cortices, with little or no space between hyphae. Cyanobacteria are mostly above and below the central mass of hyphae, and packed so tightly that whole chains are not visible. Bar is 10 µm. (Stone 2010) Fig. 2. Lobe edges in Leptogium burnetiae, showing smooth pale edges and isidia forming from single bumps on the surface. Heavy isidia formation along lobe edge is common. (Stone 2010) Fact Sheet for Leptogium burnetiae 5 Fact Sheet for Leptogium burnetiae 6