SPECIES FACT SHEET

advertisement

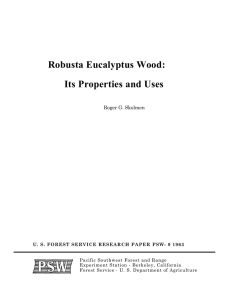

SPECIES FACT SHEET Scientific Name: Common Name: Pygulopsis robusta (Walker, 1908) Pyrgulopsis hendersoni (P. robusta) (Pilsbry, 1933) Jackson Lake springsnail Harney Lake springsnail (also Lake Abert/ XL Ranch springsnail) Columbia springsnail Idaho springsnail Pyrgulopsis new species (P. robusta) Pyrgulopsis idahoensis (P. robusta) Phylum: Mollusca Class: Gastropoda Order: Neotaenioglossa Family: Hydrobiidae Pyrgulopsis is a genus of tiny aquatic snails in the order Neotaenioglossa, family Hydrobiidae. This genus of snails is the second largest genus of freshwater mollusks in North America, consisting of over 120 species (Lysne et al. 2007). The four taxa mentioned in this document belong to the subgenus Natricola, which was erected in 1965. The taxonomic relationships between taxa in this subgenus have been recently re-evaluated using molecular DNA information and morphological characters (Hershler and Liu 2004). Prior to Hershler and Liu’s work, both Pyrgulopsis hendersoni and Pyrgulopsis new species “Columbia springsnail” were considered to be closely related to Federally Endangered Pyrgulopsis idahoensis, the Idaho springsnail, and another species, Pyrgulopsis robusta, which was considered endemic to Wyoming. Two other taxa, previously recorded in some documents as P. new species, the Lake Abert springsnail and the XL Ranch springsnail, were also considered to represent populations of P. hendersoni, the Harney Lake springsnail. Distinctions between species within the genus Pyrgulopsis have typically been made based on the arrangement and number of glands on the penes and other reproductive structures due to morphological similarities. Upon review of morphology and mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences, Hershler and Liu (2004) determined that these four Natricola snails do not merit recognition as distinct species and should instead be treated as a single species- P. robusta. Based upon this new classification, the US FWS made a final ruling that removes P. idahoensis from the Threatened and Endangered list (Federal Register 2007). The following report is a description of the biology of P. robusta, which is known to occur in four western states in the U.S. including Idaho, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming (Lysne et al. 2007). Isolated populations of P. robusta, previously considered separate species, will herein be referred to as: the “Oregon closed basin population,” (formerly considered P. hendersoni) the “Columbia River population,” (formerly P. new species) the “northwestern Wyoming population,” (formerly P. robusta) and the “Snake River population” (formerly considered P. idahoensis). Technical Description: The shell is relatively large for this genus, being 1.98-3.38 mm wide and 4.6-7.5 mm tall and is ovate to narrowly conic, with 4.5-6.25 whorls that are weakly to moderately convex (Hershler and Liu 2004). Overall color of the shell is clear white with a tan periostracum. The protoconch consists of 1.3-1.4 whorls that are completely smooth, or have a weakly wrinkled apical section. Teleoconch whorls are often shouldered, sculptured with well-developed collabral growth lines. Body whorl is often sculptured with myriad faint spiral threads. Shell is narrowly umbilicate. Operculum is ovate, multispiral and nucleus is eccentric. Tentacles are pale with darker patch distal to eyespots. Snout is light to dark gray-brown and the foot is pale-dark gray. Additional details on the morphology of this species can be found in Hershler and Liu (2004) and Hershler (1994). Life History: Pyrgulopsis robusta is dioecious (individuals possess either male or female reproductive organs) and oviparous (lays eggs) (Hershler 1998; Lysne et al. 2007). This species most likely reproduces once in its lifetime (semelparous), laying an unknown number of eggs on hard substrates. Depending upon ambient temperatures, juvenile snails hatch and disperse several weeks after being laid. In the Snake River in Idaho, the emergence of young snails was greatest in the summer and fall although information for snail emergence in Oregon is not available. Young are extremely small, less than 1 mm in length. On average, P. robusta survives 382 days, approximately one year, with evidence suggesting that some individuals can reproduce multiple times, thus exhibiting an iteroparous reproductive strategy (Lysne et al. 2007). Range, Distribution, and Abundance: The type locality for the originally described taxa, the northwestern Wyoming population, was found on the eastern border of Jackson Lake, WY, Elk Island and vicinity (Frest and Johannes 1995). Most recognized sites are in the Grand Teton National Park. Some sites near Jackson Lake have been extirpated due to rising and falling water levels. Currently extant sites occur in Yellowstone National Park and John D. Rockefeller National Parkway (Hershler 1994; Frest and Johannes 1995; Bowler 2004). The Oregon closed basin population of P. robusta was originally found at a spring south of Burns in Harney County, OR. However, this site is now dry due to groundwater mining. This population was most likely widespread in the Harney Lake and Malheur Lake areas, and the Oregon Interior Basin (Frest and Johannes 1995). Currently in Oregon, P. robusta occurs in isolated populations in the Oregon Interior Basin and in the South Fork Malheur River, in Harney and Lake Counties, as well as one or two spring sites in the Lake Abert area of Lake County, OR (Frest and Johannes 1995; Hershler 1998; Bowler 2004; NatureServe Explorer 2010). The Snake River population has been found in the Snake River at numerous locations along a stretch of 214 river miles (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2005). The Columbia River population was once common in the lower Columbia River from the eastern Columbia Gorge to Wallula Gap; Sherman, Umatilla and Wasco Counties in Oregon, and also in Washington based on the snails’ habitat needs (NatureServe Explorer 2010). The Columbia River population is currently known to occur at 17 sites in Oregon and Washington (Frest and Johannes 1995; Bowler 2004; Hershler and Liu 2004) in isolated populations from river mile 20 upstream 400 miles to below Priest Rapids dam (NatureServe Explorer 2010). In Oregon this group of snails has been reported from Wasco, Sherman and Umatilla Counties, and it has also been reported in several counties in Washington. Habitat Associations: This species of snail typically occupies coldwater habitats, predominantly large springs, as well as spring-influenced portions of streams, lakes, rivers (Frest and Johannes 1995) and reservoirs (Stephenson et al. 2004). P. robusta has been found on a variety of substrates. In the Snake River, Stephenson et al. (2004) found the species to prefer gravel to cobble-size substrates. Frest and Johannes (1995) also found P. robusta to utilize similar habitat in the Columbia River. P. robusta was found on cobbles embedded in sediments and on woody debris and macrophytes in Polecat Creek and a single tributary (Riley 2003). In southeastern Oregon this species was found on substrates ranging from coarse sand to cobble, but could also be associated with aquatic plants Eleocharis, Rorippa, or Scirpus (Frest and Johannes 1995; Hershler 1998). Due to the variety of conditions utilized by different populations of P. robusta, it is difficult to determine the variables important for habitat selection. This species has been collected from water containing widely varying dissolved oxygen concentrations, and field and laboratory studies indicate that P. robusta can tolerate a wide temperature range (Lysne et al. 2007). Populations in the Snake River have been found in water ranging in temperature from 4ºC to 26ºC (Stephenson et al. 2004). In southeastern Oregon, this species of snail has been found primarily in thermally stable, cold springs and pools varying in size (Frest and Johannes 1995). Threats: If all individuals at an isolated site are killed in one incident, the entire population may be extirpated since this species of snail is an annual species. Re-colonization of these isolated wetlands is uncertain if a population is extirpated. Each documented site is considered important in order to maintain the current distribution of this species. Perennial water quality is a major determining factor for the persistence of this species of snail at spring sites (Frest and Johannes 1995). Reducing groundwater discharge at springs or seeps may result in adverse changes to water chemistry and habitat quality in downstream habitats. Entire populations may die if sites become dewatered, due to diversion of spring outflow or lowering of the water table. Capping of springs for irrigation, stock watering and human consumption is becoming more common and other commercial uses of water such as groundwater pumping and geothermal projects pose threats to the maintenance of a stable water table and natural hydrologic function in these basins. Grazing cattle can degrade sites from trampling, fecal and urine pollution, and the removal of vegetation. Humans have also caused habitat degradation from trampling and pollution and have introduced exotic species of snails and fish to some sites. Sites in rivers and on lake margins may be threatened by impoundments and siltation. Sites in the Columbia River with populations of P. robusta have habitat characteristics approximating pre-impoundment conditions. Some sites have been lost due to dredging and channel improvements in the river. Agricultural runoff may affect the health of remaining populations. Fluctuating water levels caused by drought or drawdowns for irrigation or power generation may adversely affect lake and river site populations. An exotic species of gastropod, the New Zealand mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum), has been documented in Crooked Creek, Malheur County, and is abundant in the Snake River Basin (Frest and Johannes 2003; Lysne et al. 2007). This species of gastropod exists in sympatry with the Jackson Lake springsnail (Riley 2003; Clark et al. 2006); however, P. antipodarum competes with the Wyoming population of P. robusta and slows its growth. Conservation Considerations: Managing areas where this snail lives by restricting or prohibiting activities such as those mentioned above will help protect this snail’s habitat. The development of streams is perhaps the single most deleterious activity in arid and semi-arid ecosystems to terrestrial and freshwater mollusks (Frest and Johannes 1995). However, any activity which affects the pristine aquatic environment preferred by this species of snail will also adversely affect populations. Conservation Status: Pyrgulopsis robusta is globally ranked G4 (not rare) although at the state level in Oregon it is ranked as S1 (critically imperiled due to extreme rarity) (Oregon Biodiversity Information Center 2010). Overall, the trend of this species appears to be stable since multiple species of Pyrgulopsis have been combined to form a single entity. However, certain populations, such as the Columbia population in Oregon and Washington, and the northwestern Wyoming population are declining (NatureServe Explorer 2010). The declining trend is due to habitat degradation and loss. Prepared by: Heather Andrews Date: April 2011 Final Edits: Rob Huff FS/BLM Conservation Planning Coordinator Date: June 2011 ATTACHMENTS: (1) (2) (3) Map of Range and Distribution Shells of Natricola species Information Sources ATTACHMENT 1: Map of Range and Distribution Figure 1. Known occurrences and distribution of Pyrgulopsis robusta in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming. Image from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2005). ATTACHMENT 2: Shells of Natricola species Figure 2. Shells of Natricola species. A, B. P. robusta, USNM 874185. C. P. hendersoni, USNM 874386. D, E. P. hendersoni, USNM 892179. F, G. P. hendersoni, USNM 884547. H-J. P. idahoensis, ALBRCIDA 7568. K, L. P. sp. A, USNM 883873. Scales = 1.0 mm. From Hershler and Liu (2004). ATTACHMENT 3: Information Sources Bowler, P.A. 2004. Petition to list the Jackson Lake springsnail (Pyrgulopsis robusta), Harney Lake springsnail (Pyrgulopsis hendersoni), and Columbia springsnail (Pyrgulopsis new species 6) as Threatened or Endangered. Report submitted to the United States Secretary of the Interior, Washington, D.C., July 2004. 59 pp. Clark ,W.H., M.A. Stephenson, B.M. Bean and A.J. Foster. 2006. Snake River aquatic macroinvertebrate and ESA snail sampling. May 2005. Technical report submitted to: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Boise, Idaho in fulfillment of Section 10 permit #7999558-5 requirements. 48 pages & 14 appendices. IN Lysne et al. 2007. The life history, ecology, and distribution of the Jackson Lake springsnail (Pyrgulopsis robusta Walker 1908). Journal of Freshwater Ecology 22: 647-653. Federal Register. 2007. Final Rule to Remove the Idaho Springsnail (Pyrgulopsis idahoensis) from the list of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, August 6, 2007. Frest, T.J. and E.J. Johannes. 1995. Interior Columbia Basin mollusk species of special concern. Final report: Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project. Contrac #43-OEOO-4-9112, Walla Walla, WA. Frest, T.J. and E.J. Johannes. 2003. Progress Report, Owyhee Mollusk Inventory. Vale District BLM, Vale, OR. Hershler, R. 1994. A review of the North American freshwater snail genus Pyrgulopsis (Hydrobiidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 554: 1-115. Hershler, R. 1998. A systematic review of the hydrobiid snails (Gastropoda : Rissooidea) of the Great Basin, western United States. Part I. Genus Pyrgulopsis. Veliger 41: 1-132. Hershler, R. and H.P. Liu. 2004. Taxonomic reappraisal of species assigned to the North American freshwater gastropod subgenus Natricola (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae). The Veliger 47: 66-81. Lysne, S.J., L.A. Riley, W.H. Clark and O.J. Smith. 2007. The life history, ecology, and distribution of the Jackson Lake springsnail (Pyrgulopsis robusta Walker 1908). Journal of Freshwater Ecology 22: 647-653. NatureServe Explorer. 2010. Comprehensive Report for Pyrgulopsis robusta. http://www.natureserve.org/ Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2010. Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon. http://orbic.pdx.edu/documents/2010-rte-book.pdf Riley, L.A. 2003. Exotic species impact: eploitative competition between stream snails. M.S. Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, USA. 48 pages. IN Lysne et al. 2007. The life history, ecology, and distribution of the Jackson Lake springsnail (Pyrgulopsis robusta Walker 1908). Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 22: 647-653. Stephenson, M.A., B.M. Bean, A.J. Foster and W.H. Clark. 2004. Snake River Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and ESA Sanil Survey. Idaho Power Company Technical report submitted to: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Boise, Idaho in fulfillment of Section 10 permit #799558-4 requirements. 62 pages & appendices. IN Lysne et al. 2007. The life history, ecology, and distribution of the Jackson Lake springsnail (Pyrgulopsis robusta Walker 1908). Journal of Freshwater Ecology 22: 647-653. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2005. Draft Best Available Biological Information for Four Petitioned Springsnails in Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming, pp. 82. Boise, ID.