Document 10553713

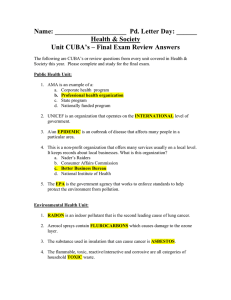

advertisement