An Ecolndustrial Assessment of Roxbury

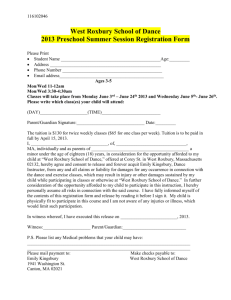

advertisement