Document 10550722

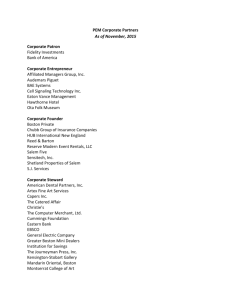

advertisement