A Museum to Grow With

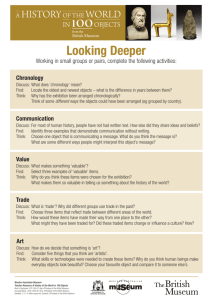

advertisement