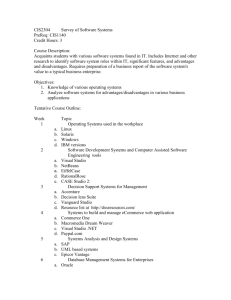

A the Hong Kong-Pearl River Delta Planning ... Yadira Taylor

advertisement