The Caliphate as Homeland: Hizb ut-Tahrir in Denmark and Britain

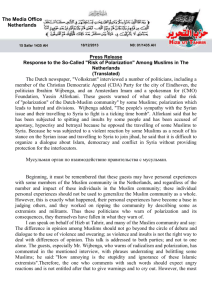

advertisement