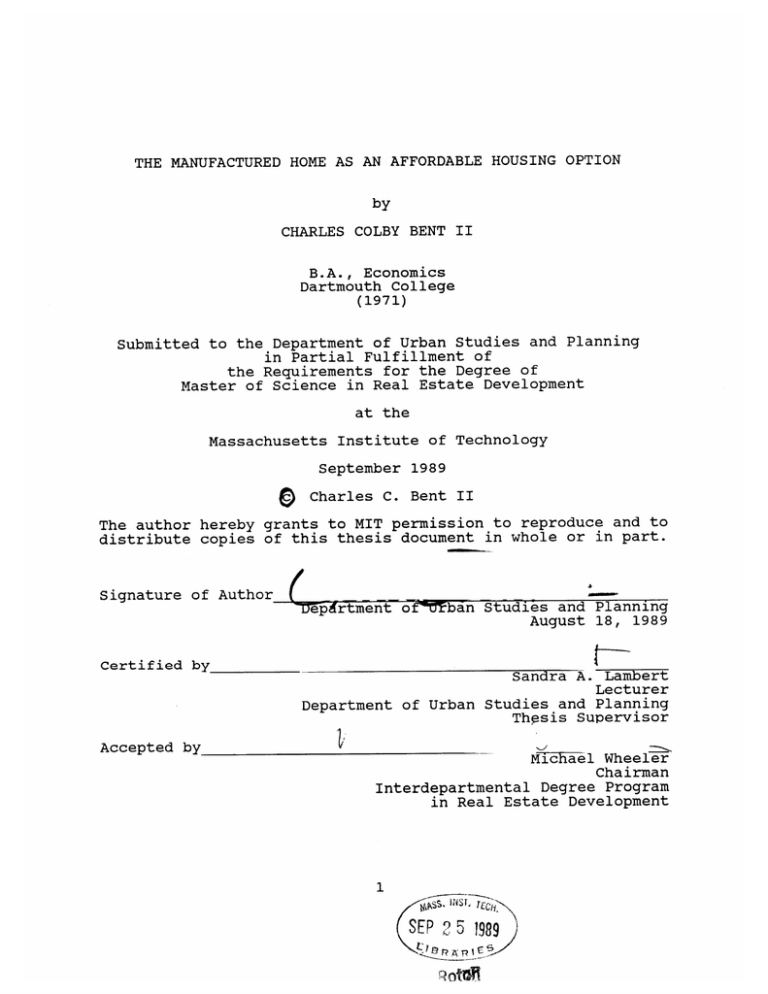

MANUFACTURED BENT B.A., Economics Dartmouth College

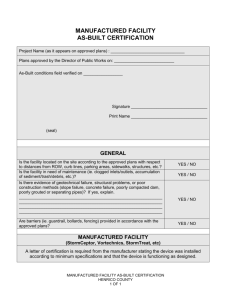

advertisement