THE BARRIOS' MERCADOS: The Creation and Transformation ... Commercial Space in Mexican American Communities

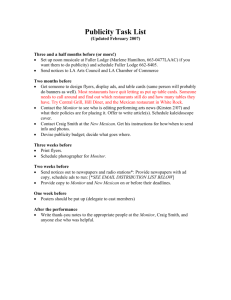

advertisement