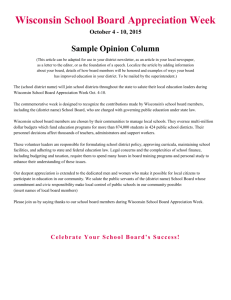

The Status of Girls in Wisconsin 2014 Report In partnership with

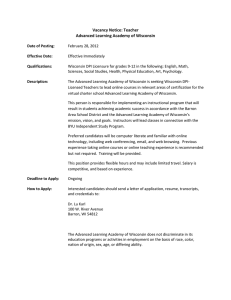

advertisement