H -C S A

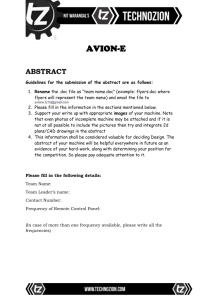

advertisement