Inuit Art

QUARTERLY

Vol. 15, NO.1

Spring 2000

Departments

Editorial

An Expanding Network of Stone Carvers 3

Focus On:

Curatorial Collaboration

I. Introduction

By Dorothy Speak

Feature

Soapstone Carvers of

East Africa: Not Isolated

and Not Alone

By Howard B. Esbin

II. Case Study: Interview with

Judy Hall, co-curator of Threads of

the Land: Clothing Traditions

from Three Indigenous Cultures

III. Case Study: Interview with

Sally Qimmiu'naaq Webster,

collaborator all Threads of

the Land: Clothing Traditions

from Three Indigenous Cultures

16

16

19

25

Curator's Choice

John Kaunak

By Maria von Finckenstein

32

Dealer's Choice

African and Inuit soapstone carvers have

much in common, from the difficulty of

procuring supplies to the challenges of

thinking creatively within the restrictions

imposed by a primarily western market

valuing a narrowly defined vision of

cultural authenticity. The Gusii carvers of

southwestern Kenya and the Inuit of the

Canadian Arctic, living at opposite ends of

the world, have evolved similar solutions

to similar problems.

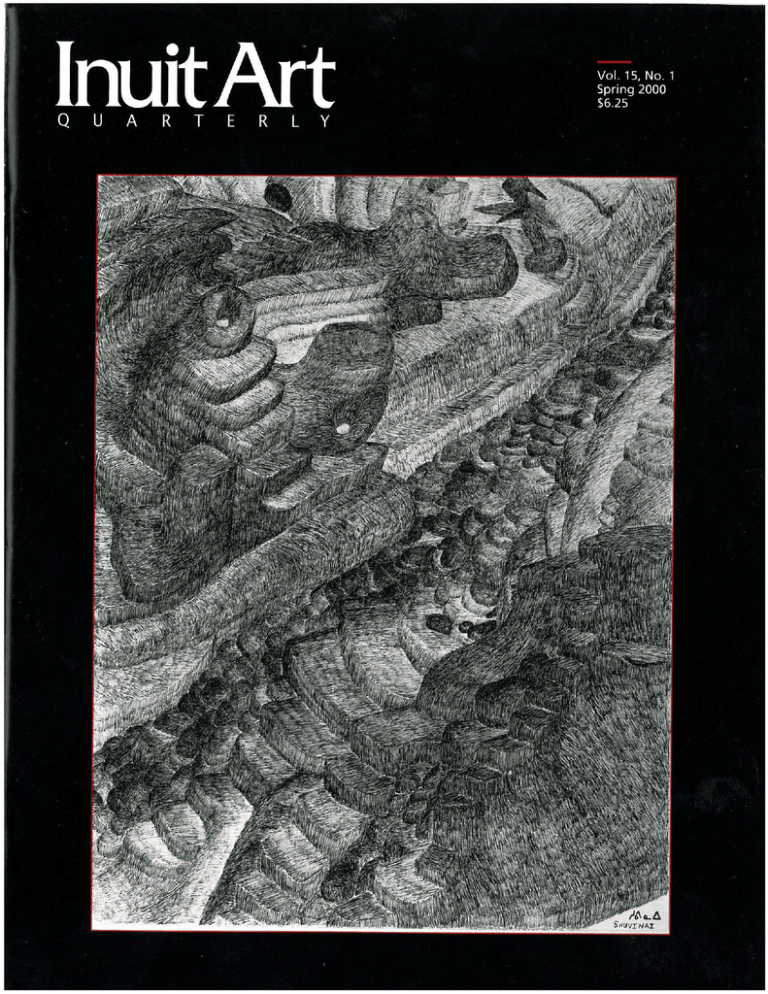

Front cover ...

Rock Landscape. 1991-98, Shuvinai Ashoona, Cape Dorset

(graphite on paper; 26 x 20 in.; collection of the West

Baffin Esk imo Cooperative).

'ofl''''';'. 1997-98. ?f\~ 4?o., P"l,fl'

Courtesy of MCMichael Canadi an Art Collection

InuitArt

<l

V

A

•

T

r •

l

•

Mosha Michael

38

Curatorial Notes

Not Just a Pretty Face:

Dolls alld Human Figurines

in Alaska Native Cultures

By Angela Linn

42

Three Women, Three Generations:

Drawings by Pitseolak Ashoolla, Napatchie

Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona

By Jean Blodgett.

46

Reviews

Books

In Search of Geraldille Moodie

Reviewed by Amy Adams

50

Update

54

At the Ga"eries

60

Calendar

63

Advertiser Index

63

Map of Canadian Arctic

64

Inuit Art

QUA

R

TER

L

Y

Vol. 15, No.

Spring 2000

Editor: Marybelle Mitchell

Managing

Editor: Sheila Sturk-Green

Assistant

Editor: Kale McCanhy

Advertising

Sales: Sheila Sturk-Green

Circulation : Kale McCarthy

Copy Editor: Claire Giga ntes

Design and

Typography: Acan

Printing: Beauregard

Publisher: Inuit Art Foundation

Editorial Maria von Finckenstcin

Advisory James Houston

Committee Maltiusi Iyaituk

1999-2000: Shirley Moorhouse

Dorothy Speak

Directors , Stanley Felix

Inuit Art Juanassie Jack Jllukallak

Foundation: Mattiusi lyaituk

Shirley Moorhouse

Nuna Parr

Okpik Pilseolak

Gideon Qauqjuaq

John Terriak

Honorary

lifetime

Director: Doris Shadboll. DC

All fights reserved. Reproduction without

written pennission of Ihe publisher is strictly

forbidde n. Not responsible for unsolidted mate·

rial. The views expressed in Inllit An Qllartt'rly

are nOl necessarily those of the editor or the

board of directors. lAQ is a member of the

Canadian Magazine Publi shers' Association.

Publications mail registration number 08986.

Publication date of this issue: February 2000.

ISSN 083 1·6708.

Send address changes, letlers to the editor

and advertising enquiries to:

Illuit Art Quarterly

2081 Merivale Road

Nepean. Ontario K2G I G9

Tel: (6 13) 224·8189; Fax: (613) 224 ·2907

(."-mail: iaq@inuitan.org

website: www.inuitart.org

Subscription rates (one year)

[n Canada: $26.75 GST incl., except QC residents: $28.76; NF. NS, NB residents: $28.75

(GST registration no. RI21033724)

United States: US$25

Foreign: Equivalem of ($39 in

your cOllmry's own currene}'; cheque,

mOlley order, VISA, MasterCard and

American Express accepted.

Charitablr rcgimalion nurnbt'r: 12103 J724 RROOOI

2

Vol. 15. No.1 Sprillg 2Q()()

EDITORIAL

An Expanding Network

of Stone Carvers

O

ne of the important functions of the

Inuit Art Foundation - publisher

of this magazine - is the connecting of

previously isolated arl isis who meet at

foundation evems and gel to know each

Olher through the flluit AI1 Qllal1erly. People

from Tuktoyakmk to Nain are lalk ing to

each other and sharing solu tions to problems and some have discovered thai Ihey

also share ties with indigenous artists

in other parts of the world.

Attendan ce by Inuit at imernationat

fo rums has contributed to the growing

network of world indigenous artists

and, in the mid-1980s, Montreal's McGill

Un iversity -sponsored exchanges of

African and Inuit carvers led to the

formation of art ists' cooperatives among

the Gusii of southwestern Kenya. It is to

further this movement that we publish

Howard Esbin's article o n the stone

carvers of Kenya (p. 4), an article that will

be of interest to artists and to scholars of

Inuit and other indigenous arts.

We think our Inuit readers will be

particularly imerested to know that their

counterparts in the hottest part of th e

worl d are dealing with the same kinds

of challenges they face in Canada's arctic

regions. In some cases, they have come

up with similar sol utions. For instance,

African and Inuit stone ca rv ers ha ve

adopted an identical division of labour,

with men quarrying and ca rving and

women sanding and polishing. Obtaining

raw materials is a problem for both

grou ps and, for the Inuit as for the Gusii,

q uarrying in vo lves unpaid labour and

ex penses that are not usually recouped

fro m the sale of the finished work.

Although the market structure differs,

tourist sales are th e mainstay for both

groups. The fad that the objects are handmade by indigenous artisans - "li ving in

a remote village in the inter ior of East

Africa" or at the top of the world - figures

largely in their market appeal, although

prices for African and Inuit decorative

objects differ markedly, as our directors

were surpri sed to note during a recent

t.rip to an Onawa retai l outlet for African

stone carvings.

Both Africans and Inuit produce from

eco nomic necess ity, the cas h ea rned

serving as a necessary supp lement 10

be treat ed in the same discourse. The

separation of art and other kinds of production seems to have been more clearly

made for African art than for Inuit an,

judging from some of the ridiculous

newspaper accounts of the latter that we

have been treated to in recent years.

The criticisms levelled at Gusii and

Inuit carvers over the years are large ly

food harvested from the land. Neither

unchallenged because of what Esbin calls

Gusii nor Inuit dissemble about the need

to earn money from what they do, and

their frankly expressed motivation is at

odds with the practice of western arlists

and assumptions abollt artistic integrity.

As Es bin writes: "The explicit avowal

of financial reward is an affront 10 a 500year western belief in 'art for art's sake.' "

"the lack of an organized, cohesive and

credible response from the arti sa ns."

Although it may ha ve repercussions for

the sale of non -western art, the debates

animating certain sectors of the western

world have little mea ning for produ ce rs

concerned with such see mingly mun-

Given that the market undeniably plays

a rol e in all all production, it is the explicitlless of financial mot ivation lhat seems to

be the problem.

Furthermore, even though so me

cO nfemporary indigenous production is

begrudgingly labelled "art," its aut henticity is pres umed to be compromised

by acculturat ive processes affecting nonwestern societies. "Indigenous artisans

and Iheir productions are placed in a

grave double-bind ," writes Esbin.

This conundrum might be mitigated if

the indigenous producers subscribed to

th e categorizing of production that is

rampant, if unenunciated, in the western world. Almost as an asid e, Esbin

deals succinct ly with the can of worms

clouding debates aboul non-western arts

and where they belong. He identifies

three categories of produaion: funaional,

decorative and fine art. The Gusii make

both function al and decorative objects

and a smaller vo lume of items produced

meet the criteria for what western critics

accept as art. Although at the beginning

of what we refer to as the contemporary

period, Inuit mad e some functional items

dane problems as the dwindling supply

of raw materials, a problem in both Africa

and the Arctic and the subject of intense

di sc uss ion at recent meetings of the

board of directors of the Inuit Art Foundation. Artists hav e co me to see that

without organization and numbers, they

have no voice. Stretching across national

boundaries, their numbers are greater

than th ey realize. MM

Inuit Art Quarterly is a publication

of the Inuit Art Foundation, a nonprofit organization owned by Inuit

artists since 1994. The foundation's

mission is to assist Inuit artists in the

development of their professional

skills and the marketing of their art

and to promote Inuit art through

exhibits, publications and films.

The foundation is funded by grants

from the Department of Indian Affairs

and Northern Development and other

public and private agencies, as well as

private donations by individuals.

Wherever possible, it operates on

a cost recovery basis.

- ash trays, cribbage boards - many, if not

most, now produce for the decorative

market. Some work is being Signified

as fine art, but the problem is that the

whole range of production tends to

3

FEATURE

SOAPSTONE CARVERS OF

EAST AFRICA:

Not Isolated and Not Alone

By Howard B. Esbin

his article imroduces th e Gusii

soapstone carvers of Eas t Africa

with whom [ work ed and li ved

in the earl y [990s. 1 [n spite of

vast differences in geog raph y

and culture, Gusii and Inuit carvers have

mu ch in co mm on. Not onl y do th ese

di sparate arti san groups share the same

chall enges faced by all carvers of stone,

they mu st also treal with a marketplace

that stands equ all y removed fro m their

communi ti es a nd their d ay· to·da y

realit ies. 2

The relationship between indigenous

artisans and western markets has been

examined in a number of ethnographic

studies (Graburn [976; Ri chter 198[ ;

Ju[es-Roselle [984; Price 1989). Artisan

communities in div erse reg ions have

developed remarkabl y similar social, eco·

nomic and aesth etic responses lO the ir

coJonjal and post·co!onial experi ences. In

most cases, a modest indigenous subsis·

tence acti vity has been transformed, over

the course of this century and especial ly

since th e Second World War, into vital

community·based enterprises with inter·

nation a l mark ets. Moreover, a lthou gh

4

each community of arti sa ns functi ons in

a discrete and even isolated manner, they

are linked in an overarchi ng global trade.

The ha ndm ade wo rk of Austr a li an

Aboriginals, New Zealand Maoris, North

and South American Aboriginals and a

great many African and Asian ind igenous

groups may be purchased in practica ll y

any large western urban market.

WESTERN AND INDIGENOUS

SOCIETIES IN CONTACT

During the 15th and 16th centuries, several Europt'an nations began to ex pand

th eir spheres of infl ue nce beyo nd the

confines of th e European land mass for

both polit ica l and eco nomic reaso ns.

Increasin gly, explorers, soldiers, mis·

s ionarie s and mercha nt s enco um ered

societi es th at had little in common with

European cult ure and its values. Given

western technological and military sophistication, these non-western sodeties were

eventu all y subju ga ted in one way or

another, a patt ern that repea ted itself

throughout the Ameri cas, Asia, Ocea nia

and Africa. Western colonialism existed

for fi ve cent uries, ending onl y in th e

mid·20th century.

Western proclivities throughout thi s

period mi ght best be described as equal

measures of inqui sitiveness and acqui si·

ti veness. The dual im perati ve between

"the need to know" and "the need to con·

tro l" deri ved from a more basic dichotomy

in vo lving two elementary poles, Self and

Other, or Subject and Object. Being quite

natura ll y ego· and ethnocentric, Euro·

pea ns viewed all save themselves in this

latt er gui se . Wh at foll ow ed was th e

wholesale and categorical reduction of all

peoples, regardless of ethni c di ffe rence,

into one subsuming generic "Other." On

this blank scree n of othern ess th e Euro·

pea ns projected whatever characteri za·

tions most sui ted their needs. Their firsl

and most prevalent view was that Native

Afri cans, Asians and Americans, given

visibly different features and lifestyles,

we re "exotic." This, of co urse, revea ls

mu ch about the Europeans and almost

nothing about th ose so labelled.

With each ensuing decade, and with

each new social encounter, western ers

returned home w ith all sorts of exoti c

things from the new places they had visit ed. These artifacts were coll ecti ve ly

referred to as "curiosities," or "curios"

for short. And it was precisely their novel

auri butes, w heth er the result of artisanai

experti se (for exa mple, th e delicate go ld

filigree jewellery of the Incas) or bizarre

image ry (seen, for exam ple, in Javanese

demon masks), th at di stingui shed such

Vol. 15, No. J Spring 2000

\

A carver works on a "spirit design"

in Tabaka, February 1992. The sizes

of such carvings range from under

six centimetres to that of the

example shown here.

"'a.. ~<l'ilon "'0.. ..'tI<l'ilo)'iIo

4'~'l.

artifacts in western eyes. Yet they were .:

not deemed "beauliful" or co nsidered ;tl

"art" per se. Such judgement was reserved ~

for western· made artifacts, like painting 6and sculpture, that reflected prevalent

aesth etic conventi ons such as representational mimesis. The latter, in particular,

with its insistence on unambiguous pic·

IOrial represen tations of id elllifiable

objects and perso ns , clearly ba rred a

wealth of artifac ts from incl usion in

western artistic canons.

Nonetheless, "curiosities" were avidly

collected by the European eli tes of th e

time. Expressly va lued for th eir exoti c

visual q uali ties, they were purposefully

displ ayed, all together, in w hat were

then called curio cabinets. As the demand

for curios grew, th ey also became com·

modified, and a deliberate trade in such

objects ensued.

A look at the 500-yea r trajectory of enabling communication betwee n the

one well·known cu rio type will serve to seen and th e un see n, these artifacts

represent the fuller story. In the late 1500s helped ensu re social stability and cula group of Portuguese sailors returned tura l homeostasis (Anderson 1970, 49).

hom e with objects produced in th e king- The Portuguese, with some adroitness,

dom of th e Kongo, located nea r what is labelled th em feli,aoes, a term mea ning

today Angola (Mlidimbe 1988) . Crafted both "charm" and "something made by

from wood, SlOne, leather and iron nails art" (Sykes 1985). The popular English

and "charged w ith magical substances," translation is "fetish."

they were designed by African arti sans to

Divocced as the y wece from th ei r

attract the man y invisible forces believed indigenous moorings, these objects stood

to be int imat ely involved with human at the ou ter limit of EUIopean experience.

affairs (Maqllet 1986,75). As mediums Wit hout a normativ e reference poinL,

Jitifaoes ha ve e licited a succession of

conceptual responses that reflea the domi·

nam spirit, o ri en tati on and va lues of

western society in each period (ibid.) .

The first pe riod , characterized by an

"

InuitArt

Q

U

••

r

t

•

l

,

I>"dr''''''~ C~a-I> <

4'>,'br

A "spirit design" carv ing from

Tabaka. Carvings o f this type are

the product of a long evolution,

the design appropriated by Kenyan

carving groups from the Makonde

on the Tanzanian coast. for w hom

they served as ceremonia l animistic

objects. The GusH began making

similar carvings in the 1970s with

the growth of the soapstone

carving industry.

Ccrl>< <l"r'"'l.. t>"dr''''' 'iIo

<l<)C""br

"'a....'tI<l1..'iIo

p<l"~r

interest in "curiosities," prevailed from

1500 to th e end of the 1700s, and was

fo ll owed by a period in which indigenou s peoples were regard ed as "savage

primitives" (roughly, 1800 to 1899). Alti tudes had hardened towards indigenous

peo ples. who were now, for th e most

pan , subjects of na tion-slates that COIl troll ed large international empires. It is

beyond the scope of this article to discuss

th e co mpl ex soc ioeconomic factors

infor ming such a senSibility. Suffice it

to say that slavery could not have fun ctioned as a vital economic force for as long

as it did yvithout it. During this period, the

initial exotic appeal of/etiraoes was forgot·

ten, and they were devalued as barbarous

and ugly. At th e same tim e, however,

[iliraoes and the like were beg inning to be

thought of as val id cultural referents by the

nascent field of ant hropology.

5

The third period. which I call the

There is further ambiguity. Along with

indigenous art-objeas-by-metamorphosis,

the 20th century. In 1905 Pablo Picasso we must now add artifacts intentionally

visited the Trocadero, a Parisian museum

produced as "art" by indigenous artisans

within whose vast collection he discov- during the 20th century. This "artered a display of 15th-century pili,aoes. by-intention" purposefully marries western

NO( long afterwards, African-inspired ele- aesthetic conventions (such as represenments appeared in his paintings. Picasso tational mimesis. perspective and fixed was not alone in his new-found appreci - base sculpture) with design motif, or

ation. In keeping with the revolutionary subject matter appropriated from indigequality of this period, western aesthetic nous sociocultural traditions. The quality,

theory and practice were characterized range and creativity of much of this work

by innovative and audacious experi- is comparable to the finest western-based

mentation. An influentiaJ group of Euro- productions.

American philosophers, writers, visual

Yet another level must be added to

artists and musicians took inspiration this taxonomy. There are also those artifrom expressive material forms existing facts, featuring both western aesthetic

outside the canon of western aesthetic and traditional design elements, that are

tradilions. As a result , all things indige- deliberately produced to generate cash.

nous appeared in a new light: "In the This category is often labelled "airport

space of a few decades. a large class of art" because of its often shoddy massnon-western artifacts" came to be reclasproduced look.

sified as "art" (Clifford 1988. 16). Maquet

These three broad classes of indigecalls them "art objects by metamorphosis" nous artifact - an-by-metamorphosis,

(1986.70).

art-by-intention and tourist art - have

generally been jumbled together in critical discourse, causing no end of confuA CONVERGENCE OF SORTS

There is no argument today that a 15th- sion. In this confusion. fine arts critics

century fftifaoe is a priceless masterpiece. and anthropologists usually reinforce

Yet one might find such an object in both each other's perspectives; the artifacts

fine art and ethnography museums. are not considered "art," nor are they

No such ambiguity exists, for example, considered culturally authentic. Consewith regard to a 15th-century painting by quently, the three classes are tarred with

Botticelli. In other words, the indige- the same brush.

Critics are disturbed that monetary gain

nous identity of the artifact is still an

issue. Ironically, the same exotic prop- is such a significant motive for indigeerties that appealed to western society nous artisans. The integrity of the artisans

500 years ago retain their principle value and their work is thought to be comprotoday. The only real change is that con- mised. Indeed, explicit avowal of an

temporary western society now catego- interest in financial reward is an affront

rizes these artifacts more specifically as to a SOD-year western belief in "art for

art or ethnography. As Clifford states: art's sake." What is also often denied or

"The fact that rather abruptly. in the space overlooked in these criticisms is that the

of a few decades, a large class of nonmarket is an omnipresent, albeit subtle,

western artifacts came to be redefined as force illlegrai to the production of all

art is a taxonomic shift that requires criti- aesthetic objects, western and indigenous.

cal historical discussion, not celebration" traditional and modern. Professionally

produced artifacts, regardless of cultural

(1988.196).

provenance, quality or purview, are

designed to be marketed (Esbin 1991).

Indeed, professional artisans ultimately

look to their specialized markets for both

approbation and financial compensation

(Grampp 1989). Academic discourse in

conjunction with market demand ultimately informs and shapes what artifacts are produced. Consequently, the

complex socioeconomic provenance of

such productions is overlooked in favour

of simpler frames of critical reference.

period of the "ethnic artist," encompasses

6

The same critical discourse also calls

imo question the authenticity and consequent validity of contemporary indigenous artifacts. For example, some art

historians and anthropologists contend

that such objeas are culturally unauthentic

because of the unwitting acculturation

of the artisans and the demise of their

indigenous traditions (Jules -Rossette

1984). Such value-laden norms persist as

the standard for any artifact's cultural and

aesthetic worth within the western world.

These three broad classes

of indigenous artifact art -by-metamorphosis,

art-by-intention and

tourist art - have generally

been jumbled together

in most critical discourse,

causing no end

of confusion.

This places indigenous artisans and

their work in a double~bind. The general

process of acculturative reinterpretation

responsible for the global trade in indigenous artifacts in the first place also

provides its basic mode of commercial

cross-cultural communication. Artisans

"attempt to represent aspects of their

own cultures to meet the expectations

of image consumers" (ibid., 1). Paradoxically, western aesthetic and market principles are translated into non-western

idioms only to be transported back to

western markets.

This dynamic and complex indigenous

production system calls for objective

analysis: When does innovation become

tradition? Who is to judge? And against

what criteria? 11 is not solely a question of

motivation, authenticity and tradition,

Vol. 15, No. I Spring 2000

althoug h each is an important determinant. Rather, the work of co ntemporary

indigenous artisan s mu st be co nsidered

dired ly, experientially and holisti cally. It

can then be seen as "deeply embedded in

a comp lex culImal eco log ical system and

transce nd[ing] it. [Such] work can be

viewed both ways, singularly as artifactin-context or as art-standing-by-itseIL

and binocularly as a crea tive work possess ing bOlh local hi story and comparative sign ificance" (Ames 1992,75).

THE (iUS .. : A CASE STUDY

Whil e the ori gi ns of the Gusii are

unknown, it is thought that they emig rated from central Africa to the highlands of the Lake Victori a basin during

the past five centuries. Abou t 250 years

ago, the Gusii reached their final haven, a

then sparsely inhab ited elevat ed plateau

in southwestern Kenya. The entire high land zone came to be known as GusiiJand.

Th e plateau's rugged and isolating features, which afforded scc urity, also

induced radical and lasting changes in

Gusi i social organi zat ion, seulement patterns and land use (LeVine and LeVine

1966). Principally, they had to g ive up

th ei r pastoralist life and their cherished

cattle herds. New subsistence activities,

including agriculture and ironworking,

gradually developed as the basis of highland Gusii socioeconomics.

In th e 1850s the Bomware, a Gusii

subclan, arrived in the highland's southwes tern corner. Their choice of settlement was fonunate. II was stratcgica ll y

sited, very fert ile and had large deposits

of th e mineral steati te, popularly known

as soa pstone. The site came to be called

Tabaka - now in th e administrative district of Bosinange - and it was to become

the epi ce ntre of contemporary Gusii

soapstone carving.

The Bomware learned to exp loit the

mineral 's seve ral utiliti es. Soapstone

powder was used as a cosmetic and medicine (Ochieng 1974; Maranga 1987). It

was soft enough to be ca rved easily with

simple tools but durable enough to retain

ilS fini shed form. From it they fashioned

th eir powers of careful observation. They

are able to sift through myri ad visual

details and idelllify those th at are relevant from those Ihat are ex tr a neo us

(Gamb le and Ginsberg 1981). The practical neceSSity of being abl e quickly and

efficiently to scan wide expanses for

hidden threats is obvious.

Field independence thus contributes to

an increased capacity lor global processing

and for inferring spatial relati ons hips

(C lark and Halfons 1983). Just as an individual's aplitudes and proclivities reflect

the dominance of one hemisphere of th e

SOCIOHISTORICAL

brain, so maya society's. Acco rding ly,

FOUNDATIONS OF VISUAL

field independent societies, with their

COGNITION

Gusii carve rs today readily ack nowledge specialized cognitive capacities, appear to

th at th e ir specialized knowl edg e and display a right-brain bias (Sinatra 1986;

ski lls constitute a priceless "inheritance" John-St e in er 1985). Indeed, Sin atr a

frolll their ancestors. This popular char- (1986, I) characterizes such etlmic groups

actcrization aptl y encapsulates a vita l as "seeing-proficient peoples." When the

hi story and tradition; for a society'S world Gusii became sedentary they jettisoned

view is guided by a blueprint of socio- behaviours th ai were no longer approcultural knowl edge and a corresponding priat e to thei r new context. Howeve r,

interpretative system (Holland and Quinn observation-based training, its worth still

1987). A society's response to particu- evident. survived.

Consequently, when th e Gusii first

lar existenliaJ and ecological co nditions is

perpetuated by its educational strategies. encountered soapstone, they were al ready

Sociocultural knowledge consists of dis- predi sposed socioculturally to see the

till ations of practice drawn from a social mineral's visual properties and va lu es.

gro up 's everyday life - in other words, This new geographically specific phe"what people know in order to act as nomen on provided additiona l impetus

they do ... make the things th ey make ... for a continued reliance on visua l cog ni [and] interpret their experience in the tion. Thus, the subsequent evolution of

the more specialized conceptual and prodistin ctive way they do" (ibid., 4).

Such social knowledge has two facets: cedural ski lls that soapstone des ign and

knowledge holV and knowledge Ihar. This production demanded may be seen as a

is direct ly related 10 occupational tasks. culturally sanctioned and socially conCross-cultural studies have show n, for struoed visually oriented system grounded

examp le, th at "Mexican children from in traditi onal procl ivi ti es. Writing abou t

families occupied by pottery-making per- lan g uage, thought and consciousness,

formed beller on tests for conservation of Vygotsky (1978; I98Ia; 1981b; 1987)

substances using clay, than children fTOm examines how such social construct ions

other famili es of comparable socioeco- bl"Came transmilled through chHd-rearing

nomic status ... in other trades" (Berry and socialization processes. Studies have

shown that thi s sociohistorical transm is1988, 234).

sion

ultimatel y cOlllributes 10 a dist incConsequently, the Gusii, who had been

pastoralists for many centuri es, literally tive perceptual ori entation that, in turn ,

had at hand a distinctive sociopsycho- reinforces aesthetic sensibilit y and outlogi ca l heri t.age and ori entati on. Given look (Berry 1988; Fisher 1966; Maqu et

t.he demands of nomadic existence, which 1986; Whiting 1963).

entai ls wandering in an ever-changing

terrain, they are consid ered to be "field

independent." This means they can eaSily

iso late specific elements within a complex visual field . Indeed, both hunting

an d pastoralisl societies are noted for

s mall pots for snuff, herbs, medicines,

coo king fat and cosmetic oils, pipes for

smoking, small stools, and baa, an ancient

African game (Ochieng 1974; Maranga

1987; Eisemon et al. 1988). By 1900 these

carv ing sk ills had been passed on to a

numb er of Bomware famili es (Tile Daily

Natioll 1991). Specialized art isa nal ski lls

w ere historically the province of certain

Gusii s ubel ans. This knowl edg e was

protected by ensuring th at sons always

married within their kin ship group.

7

A Gusii woman finishes

small animal figurines

depicting the "Big Five"

of the Serengeti: lion,

leopard, rhinoceros. ele·

ph ant and giraffe. These

are seen by First World

consumers as prototypica lly African symbols.

These carvings can be

seen in shops around the

world. from Auckland.

New Zealand to

Disney World, Florida.

Tabaka, April 1993.

p<l"'E,.rl>C<Io <l~o.... q, 'f' .... c-q,"'.6.~q,

'"1J<lL a-~ <J<>c-br

"'a..

O"'''~n'f'Lcr.

LO'""b~L..&c

p<l"'I;.·r. <l~Q..'f'c

<lL 'P'-c-'Io",.6./

"a.

•

•I

.,

"1J <lLcr~

In spite of Gusii carve rs' "overwhelming compl exi ty of visual experience," a "transm ission of effecti ve visual

schemata" from one generation to anoLher

continu es unabated (John-Steiner 1985,

82, 90). In other words, the cognitive

developme nt of GusH carvers, mediat ed

as it is by "socialization, learning and

experience," is nattually oriented towards

the visual processing of information (Das

1988, 50). Such an "indigenous preference for cog nitive processing" decidedly

undersco res th e success of kinaesthetica lly demanding tasks like carving (ibid,).

In other words, Gusii carvers and th eir

enve loping society have been histo ri cally animated by a specialized cognition, language and communication that

co ntinues lO be vi tally visual in nature.

8

'" \

CONTEMPORARY SOAPSTONE

CARVING

Portuguese control of East Africa, which

lasted for two centuries, was supplanted

by the British around 1750. In spite of

the g radual opening of the East African

interior, Gusiiland remained remote and

was conq uered on ly in 1895, The highlan ds had originally been intended as a

British co lony, but the high cost of the

conquest and th e continued belligerence

of the Gusii made this impracticable.

Instead, the British looked to the development of their new territory. Like the GusH,

th ey sa w ag riculture as (he economic

mains tay and thus precipitated changes

in Gush life as d rastic as those experienced when the Gusii first settled the area.

The GusH were inexorabl y introduced

10 both a cas h-based economic sys tem

and its mass-manufactured commodities.

Bomware soapstone carving was irrevocably redirected as well. In 1914 Richard

Gethin became the first licensed trader in

the newl y established territory. He saw

some Bomware ca rving and became

intrigued by the slone's commercial possibilities as an exotic cmio and as a laic

powder. Th e carvers, however, would

not cooperate. Ult imat ely achieving hi s

goals through coe rcion, within a few

years Ge thin controlled a small trade in

soa pstone ca rving and talc production .

During the decades between the world

wars, British Gusi il and socioeconomics

continu ed to revolve around agriculture.

Soapstone was va lued primaril y for its

laic powder, used as a cosmeti c, and this

talc trade continu ed until the end of th e

1940s. Carving was a minor activi ty at

best. OccaSional ly, British settlers would

commi ss ion th e Bomware to produce

specifi c desi gns. In th e 1930s a Catholic

missionary unsuccessfull y attempted to

use soa pstone ca rving as a basis for a

work program for the un employed (Tile

Daily Natioll 1982), With the end of the

Second World War, nationalists across

Africa intensified efforts to win self-rule.

Ult.imately th eir aspirations were advanced

by a number of international sociopolitical trends.

Kenya's independence was achieved

in 1962. In that year, there were perhaps

100 carvers in Bosinange and few women

were involved in soapstone production.

AI! were members of the Bomware subclan. These men carved on a pan-t ime

basis for tourists who wanted souvenirs.

Their earnings supplemented their cashcrop ag ri culture. With independence,

however, Kenya exper ienced a dramatic

acceleration in socioeconomic activity.

Thi s included the development of modern infrastructure, the introduction of

universal primary education, rapid populat ion growth and the adve nt of western

mass- markeltourism.

Demand for soapstone carvings began

to increase. AI firs t thi s was met by a

cor respond ing increase in the num ber

of Bomware carvers. By the early 1970s a

few men from contiguous subclan territori es began carving as well. Western market demand continued to rise throughou t

the late 1970s and 1980s. As a consequence, more and more carvers entered

Vol. 15, No. J Sp ring 2000

Each day after school, young boys

congregate at the carving sites

where their adult male relatives

work. There, they assist the men

in small tasks, and attempt to carve

themselves, using small, discarded

bits of stone and improvised tools.

Tabaka, April 1993 .

..ob<A<]' <l":Jrl L .6.c-Lo-<]'i»C

~a.. ~<]('\.t>'i>~o-Ir p<lL!:rr

••

the market. SeveraJ local cooperatives were

established. Given the increasing demand,

the wives of Bomware carvers joined in.

In keeping with traditional values, the

couples instituted a division of labour

whereby the men continued quarrying

and carving while the women assumed all

finishing processes. At present, there are

approximately 1,500 adulL male carvers,

2,500 adult women sander-polishers and

some 1,000 children and youth of both

genders serving as apprentices.

MARKET APPEAL

The visual appeal of a Gusii soapstone

carving derives from a complex interplay between exotic and aesthetic factors. The Taw material itself is visually

pleasing. Gusii soapsto ne occurs in a

variety of hues of differing intensities

ranging from bone white, through ochre,

pink, orange and brown. It is also sometimes found in black and grey. Often,

the soapstone appears striated with agatelike bands admixing many of the hues.

Skilful carving and polishing enhances

this natural colouration and brings out a

high lustre as well. Western consumers

also value the fact that it is handmade by

an indigenous artisan living in a remote

village in the interior of East Africa. These

factors all help to determine the western

market value of a Gusii carving.

InuitArt

0:

U

A

IT'

I

,

f

The carvings that have been produced

since the Second World War fall into three

basic categories. There are functional

items such as vases, bowls and jars. There

are also decorative items such as animal

and human figurines. Typically, westerners use both as display pieces. African

motifs are integral 1O each category. For

example, a cup will be carved in the

shape of an elephant head with its trunk

serving as a handle, or the surface plane

of a box lid will be incised with a repetitive palm leaf pattern. Figurines will

depict stereOlypical images, for example, a crouching leopard or a warrior

with a spear. In addition to these more

overt visual qualities, a carving's overall

design and construction must accord

with western aesthetic conventions such

as composition and balance.

The third ca tegory consists of oneof-a-kind carvings. These creatively and

skilfully fuse western aesthetic conventions with tradHional Gusii subject mat ter. The western market, for the most

part, treats these carvings as fine art. This

is apt, for the very few GusH carvers who

produce such work ha ve been well

grounded in western-based art education programs. Elkana Ongesa, whose

sculpnrres grace the entrances of UNESCO

in Paris, the United Nations in New York

and Caltex Oil in Houston, is typical. He

studied fine arts at Makerere University in

Uganda and McGill Univers ity in Canada.

In comparison to the great number of

functional and decorative carvings that

have been produced, the output in this latter category remains quite small. Moreover, while its symbolic worth is high,

its economic value for the Gusii remains

negligible.

The growth of the Gusii cottage industry over the past 30 years is a direct consequence of the rise in overall western

demand for indigenous handiwork.

However, such demand is both cyclical

and fickle. For example, at the beginning

of the Kenyan "boom" in the mid· I 970s,

two other indigenous products - wood

carvings and sisal carry-bags, called

"kiondos" - were much more popular

and accessible. Both could be exported

easily and in significant quantities

because they were relatively inexpensive to produce. Sufficient quantities of

wood and sisal were readily available,

and there was a trained and inexpensive

labour force of the right size. Western

fashion trends, and inexpensive Asian

copies, ended the demand for kiondos.

Western environmental concerns also

eclipsed demand for products made from

wood. Since then, not surprisingly,

Kenya's export of soapstone carving

has matched and then eclipsed that of

kiondos and wood carvings. I believe that

demand for GusH soapstone carvings is

now at its peak. Indeed, large buyers

from Europe, the United Kingdom and

North America have indicated to me that

they are overstocked in soapstone carvings

and are actively searching for alternative

products.

9

Two women from an

extended work group finish

carvings, Tabaka, April 1993.

The profusion of vases, all

repeating the same design,

represents the very lucrative

mar ket for hand-made.

mass-manufactured items.

It is quite possible for an

order to be placed for

thousands of such items.

L~?~ <ll~ ~ 'f''- C-q,.L\.6:~C t>~d,A"1T

~o.. ~<lL.a-

A typica l Gusii stone quarry, Tabaka,

February 1992. Each of the several

quarries in the area around Tabaka

holds a distinctive soapstone. in

terms of both hardness and colour.

While geological surveys suggest

that the land around Tabaka holds

enough stone to meet the demands

of the local cottage industry for some

time to come, experienced carvers

have noticed a decl ine in the overall

quality of the quarried stone.

Jt>~ t>'dl",~

<UN''','',

P<l'~

<I<> ~"br

10

remark ab le. Animating this comp lex

endeavour is the Gusii's pred il ect ion for

adap tation an d innovation, itse lf a consequence of the sustained learn ing style

that is central 10 the Gusii's particular

experience.

At least n ve generations of GusH have

been involved in soapstone carving. Each

generation has passed on relevam knowledge to the next through traditional educational processes. Yet each generat ion

has also so ught 10 improve and standardize various facets of the prod uction

process. For exa mple, women expe rimented to renne th e sand ing and polCOTTAGE INDUSTRY

ishing sk ills needed to bring out the

luminos it y and colour of a carving. Such

STRUCTURE

The co ttage industry derives its st Tue· ingenuit y also led to the discovery and

lUre from the phases of its marke ting use of a local leaf as a form of natural

cycle - produd design, produdion (quar- abras ive in the production process long

rying, carving, sa nding, polishing) and before sandpape r was ava il able.

With such a dynami c social learning

sa les. It has neither a centralized hierarch ica l leadership nor any convention- process, overa ll expertise among cottage

all y organ ized local body overseei ng its indust ry wor kers has increased prop oroperations and mechanisms. BUL it does tionally from generati on to generat ion .)

have internal logic, cohesion and consis- However, in creased m a rket demand

tency. Moreover, w hile some structural for soapstone carvings during the past

features of the industry mark eli.ng cycle 25 years has limited expression of th is

ap pear crude (usin g axes to quarry Slone · proficiency. In today's extremely compeand oxen to transport it) and others appear titive in dustry, a carver's co ncerns for

naive (prelimi nary labour costs such as quality are overshado wed by his need

quarrying, transport and fin ishi ng are to produce carvings in q uanti ty. Ind eed,

nol always factored into local w holesale most middl e -aged carvers believe th e

pricing formul ae), in most respects the quality of execu ti on has eroded over

industry is quite sop hi stica ted. With out the past two deca des.

a modern communica ti ons infrastru cture, the nearest telephone or fax being

30 ki lomet res away, the speed and vita lity

w ith which th e industry operates is

Vol. 15. No. I Spn'ng 2QO()

A carver begins a SCUlpture, Tabaka,

February 1992. He has blocked out

the rough form of his intended

design; in this case he is carving

a flat soap dish. The tools pictured

next to him are locally made,

although some tools used by

the Gusii are imported, typically

from China.

"a.."~<N1 N<lc-<io><io "a..cr"f" <1-L...f

'"'f~nr nJr 41'n

There are al least 200 distinctive products being carved in Bosinange today

and these fall into the decorative and functional categories described earlier. Each

generic cat ego ry has many variations.

The development and proliferation of

such des igns occurs on an ad hoc basis

and this results in a somewhat amorphous

common inventory from which anyone

can borrow. Most of the designs w ithin

the overa ll invent ory pool have a discernible provenance and chronology. Older

carve rs in Bomware can remember wha t

producl lype was imroduced when and

under whal circumstances.

Inuit Art

Q

U ..

,

T (

•

l

•

Yet the competitive nature of the market has led to family specia li zation in

certain product types. With such a broad

inventory range, it is impossible for one

carver to master them all. Today's cottage

industry is largely controlled by local

middlemen. An "outsider" customer will

usually brin g an order to a wholesaler,

who finds it expedi en t to give that order

to someone who can ca rve it quickly and

well. The middl emen are aware of which

famil y carving groups, given their respective ex pertise, ca n most effeclively meet

which orders.

There are 11 acti vely mined quarries in

Tabaka. Everyone involved in soapstone

production an d markeling must have

access to one of the quarries for their

raw mat er ial needs. Quarries are si mple

open pits into which carvers descend on

foot to extract stones. Most occupy less

than five hectares. The land immediatel y

surrounding th ese sites is given over

to resid ences and farm s. Each quarry is

privately owned and referred to locally

by the owner's nam e.

Given the industry's competitiveness,

larger-volume custom ers will now rent

an entire quarry for up to two weeks at a

time to satisfy their raw material requiremellls. During thi s period, th e quarry

will not be available to any other middlemen or carvers. In 1993, for exampl e, a

GusH wholesa ler, based in the Un ited

Slales, remed IwO of the largest qu arries for severa l weeks 10 ensure she had

enough stone to produce 10,000 pairs of

candlesticks. The larger quarr ies remain

continually rented out throughout the

year and so it is increasingly difficult to

oblain carving mat erial The relative softness of soapstone prohibils the use of

heavy equipment in its mining. Rather,

workers manually "pry rocks from

the hillside with crowbars and levers"

(Eiseman et ai. 1988, 225) . They then

use two-man rip saws to cut the quarried

stone into rough blocks of various sizes.

When lhe stone has been excavated and

paid fo.r, it is transported from the site

to a production area, which marks the

next phase in the cycle. Trucks, donkey

carlS, oxen chained 10 large boulders and

human ponage are all used in the transpon process.

11

The production and marketing of

soapstone carving is divided along

gender lines. Men quarry and carve,

whi le women, for the most part,

finish the carvings and market

them. This traditional division of

labour generally finds bot h men

and women working t ogether in

extended group ings such as the one

in this photo. Tabaka. April 1993.

Jl>~r 'b'C'tJcrr c

~a.. "1.J<lq,bnr r":» c.<1":Jcn~c "Q.,":J<lq,n..."rc

<1' 0.. "f'C L"'O""\bc~"...:J:'c

Carver Thomas Mogendi works on

a carving, Tabaka, January 1993. The

object' s form has been roughed out

and the artist uses a file and knife to

refine the component shapes.

LL" jl,,"'n ,",a.."'''V<l'')'' !, ..o<ln.. 1993r

SoapSlOne is a mineral composite, Various

mixtures of sericite and kaolin, a long

wi th various other mineraJs, exist w ithi n

any given deposit. Certain quarries produce particuJar mixtures thai have a characteristic colour and hardness. Colours

are referred to loca ll y by their Eng li sh

designations - white, ye llow. pink and

brown . This prov ides loca l indus u y

workers with a usefu l cod ing system for

qui ck referen ce an d identifi ca tion. As

not ed earli er, soapstone colours are more

nuanced than these designations suggest.

Some Slone has one dominant co lour

throughout; others feature a va ri ety of

colours and ton es. Some have agate-like

12

banding, while others are mottled. Sensitive arti sans attempt to maximi ze th ese

colours through skilful carvi ng, sanding

and po li sh ing. While geological surveys

suggest that there are extensive deposits or

soapstone lying under the hills ofTabaka,

not all of it is suitable as carving materi al.

Older carvers comp lain th at the present

quarr ies, most or which have been open

since the mid-1960s, are fast being dep leted

or the belter grad es or sto ne.

As w ith all busin ess endeavours, th er.e

is a defini te correlation in carv in g

between profit, cost and production lime.

Carvers know exactl y wha t is needed to

produce any given design they have mastered in lerms or ston e quantity, 1001s,

water, sandpaper and so on. They also

know exactl y how many units or a given

d es ig n they ca n produ ce in a give n

period or time. Manag ing these two compon ent s well is esse ntial to commercial

success.

or the esLimated 1,500 carvers operating

in Bosinange today, abou t one-third do

nothing but ca rve. That is, they do not

engage in the local wholesal e trade or

buying an d selling carvings. The balance

of th e carvers are involved in marketing,

It is not unusua l ror a carver-trad er to

subcontrad a large order to other carvers,

or for those carvers to subconLract parts of

this order in turn. It is, th erefore, often

difficult to ascertain an item's upperlevel se ll ing price; th ai remains to be

det ermined by the whol esa ler and the

outside buyer, The carvers have two local

venues for marketin g thei r carvi ng. The

first is throug h the cooperati ve system

of whi ch they m ay b e me mbers; th e

second is through lhe open market, which

they rerer to as "carving fo r wholesale,"

Carvers earn from und er $300 to over

S 10,000 an nually from their work. Th eir

success d epends on sk ill, energy and

ambition. In a ll, some $2 million is

earned by the community annuall y.

There is a d istinct sequence in the use

of too ls dur ing th e ca rvi ng process. A

carver b eg ins by paring down a raw

block or stone with hi s mad1etc. A rough

Val. J5, No. J Sprillg 2(}(){)

approximation of the final shape is

carved oul. The carver gradually refines

this rough shape using various 1001s such

as a knife and rasp. In keeping with the

egalitarian traditions of the past, male

work groups gladly share their tools with

those in need. Each product type has a

specific set of design and carving requirements which must be mastered.

However, mastery of one product does

not easily translate 10 others. Even the

most experienced carver will have difficulty with certain passages while fabricating less-familiar products - hence the

importance of specialization. Throughout

the entire procedure, carvings are soaked

and resoaked in water so that the porous

stone will remain soft and easier to carve.

When the SlOne softens it is also imperceptibly enlarged, which tends to expose

hidden fractures that, when detected

early, can save the carver time, energy

and money.

There are two distinct production processes that women alone are responsible for: sanding and polishing. This is a

recent development of the past two

decades. Both production steps are laborious, repetitive and time consuming.

The sanding process involves a series of

adivities ranging from sanding to soaking

carvings in water. As the sanding progresses, the women resort to ever-finer

grades of sandpaper. In keeping with tra ditional norms, daughters learn these

skills by obseJVing their mothers at work.

Carvings are usually ordered through

the aegis of the wholesale sector, which

consists of men and women, families and

cooperatives. In IUrn, these various actors

channel direct orders to the producers.

Some of the local wholesalers operate

their businesses from outlets along the

Tabaka road. Others maintain their businesses at their homes. Each of the cooperatives manages a separate showroom.

The wholesale sector has a number of

InuitArt

Q

"

~

~

r

[

•

, r

Small warehouses line the fivekilometre Tabaka road. featuring

the carvings produced by members

of the extended family groups.

The profusion of carvings in all

sizes, designs and qualities is typical.

Tabaka, April 1993.

.6.~->~~<I~C~b <Dx:t>,.k~

crt>"<l"",%~"t> .. ->cr

levels. A ca rving may pass through five

transactions before it is shipped from

Tabaka 1O either the national or export

market. In broad terms, there are insiders

who sell to other insiders locally, and

insiders who sell to outsiders - merchants

from either the national or international

markets. Insiders may sell lO outsiders

who visit Tabaka or they may travel to

other points in Kenya 1O sell their merchandise. Local cooperatives are organized 1O sell large quantities directly to

the export market.

The carvings being produced and

wholesaled in Tabaka are destined for

two interconnected western markets. The

national market is coterminus with Kenya.

Each year, tens of thousands of Germans,

BrilOns, Italians and Americans visit the

country. A network of retail stores, kiosks

and mobile street and beach vendors sell

souvenirs, including soapstone carvings,

to these tourists. Many of th e western

countries comprising the export market

are home 10 businesses that retail soapstone carvings. Many national market

enterprises also operate as wholesalers

by reselling their carvings to this export

market. There are many venues through~

out the Wes t specializing in handmade

indigenous artifacts, including stores and

catalogues.

"'Q.. ..~<lL~a-

CONCLUSION

The Gusii, along with most other ind.igenous artisans, must deal with the profound challenges stemming from the

changing, as well as changeless, demands

of the western marketplace . These

include the problem of producing and

marketing carvings that are made from

the same materials and feature the same

subject matter but that stand at opposite

ends of the continuum in temlS of quality;

the impact of pervasive cri ticism from

art critics and anthropologists as well as

th e lack of an organized, cohesive and

credible response from the artisans themselves; the continued importance of carving

as an economic mainstay; the implications

of dwindling raw materials for production, and the socioeconomic implications

for coming generations of a maturing

co ttage industry. The artisan communities continue in their labours, believing

they are isolated and alone in confronting

the cha llenges, problems and opportunities created by their market, which,

ironkally, is a marketlhat they share with

many other such communities.

In the mid-19BOs, Gusii and Inuit a.rtisans came together both in Tabaka and in

northern Quebec to share experiences

and learn from each other. The most tangible outcome was the development of a

cooperative in Tabaka modelled on the

Inuit cooperative system. The book Stories

ill Stolle was published as well. It featured

myths and stories from both societies,

complemented by photographs of the

carvings of both groups. Finally, Gusii

13

and Inuit carvings were featured in a well-

Anderson, J .

attended travelUng exhibition in Canada,

Kenya and the United Slates. It is obv ious, however. thal such exchanges could

1970 The Strll9gle for tile ScI/ool: r/le lllferactioll of

Missiollar)', Colollial GovernmCllt alld Na tionalist

Emerprise;11 tile Dew/opmmt of Formal Educalioll ill

Kenya. Lond on: Longman (Development lexls).

accomplish a great deal more. Sadly, they

remain all 100 rare.

It is my hope that articles such as this

will show that indigenous artisan groups

like t.he Gusii and Inuit are neither alone.

nor isolated .

Howard Es/Jil', director of HOPE. a l'Oitmlar organiza·

tioll raising fU llds for charities, completed his doctoral

resellrch ill allthropology at McGill Unil'ersilY i" /998.

His dissertatioll fOCI/sed 011 IIII' socioeCOllomics of tile

Gusii soapstone canrillg il/duslry.

NOTES

I The Gus ii, a Banlll people, have been living

in the h ighlands of western Kenya fo r aboUi

200 years (Och ieng 19 74). The Bantu a re a

w id ely di spersed et hn ic group consist in g of

man y different peoples living throughout equatorial and southern Africa.

2 I usc the more neutral term "art isan" rather

than "craftsperson" or "artist," terms that unduly

categorize the anifacts each produces into separat e classes, co mpelling the unresolved - and

here unn ecessary - debate as to what is "art"

and what is "craft."

3 The sk ill level of the est imated 1,500 carvers

operating in Bosinange today may be situated on

a bell curve. A minority sits at either end. The first

is d isti nguished by its lack of skill. This group is

further subdi vided into {hose who arc novices

and those who, while experienced, remain deficielll. The other m inority is d istinguished by its

virt uosity and by ils ability 10 innovate new

designs. This laller skill is relatively unim portant

in the industry as il exists loday. given the economic imporlance of standardized production.

This ca tegorization, however, also und erscores thai there are two aspects of art isana l

expertise (Halano and Inagaki 1996). The firs t

d ifferen tiates the master from the novice and is

based on proficiency in conceptual and p rocedural know ledge and skills (Perkins et al. 1977).

The second differellliates the routine expert from

the adaptive expert and is based on manipulating

conce ptual and procedural knowledge 10 new

and/or di fferent ends.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ames, M.

1992 Cannibal Tours alld Glass Boxes: The Alltllropology ofM llselll1ls. Vancouver: Uni versity of Brit ish

Col um bia Press.

Berry. J.W.

1988 "Cognilive Val ues and Cogn itive Competence aillong Brico leurs." In ll/digmolls GJgllitioll:

FUI/ctiolling ill ell/lUral Call/ext, edited by J.W. Berry.

S. H. Irvine and E.B. Hunt. Dordecht : Mani nus

Nijoff.

Clark, LA., and G.S. Halfons

1983 "Does Cognitive Style Account for Cultural

Differences in Scholastic Ach ievement?" Journal

afCross-Cultural Psychology 14, no. 3: 279-96.

Clifford, J.

1988 The Predicamellf ofel/llllre. Cambridge. MA:

Harvard Un iversity Press.

The Daily Nmioll (Nai rob i. Kenya)

199 1 "The soapstone carvers of Tabaka." May 7.

1982 "History of the soapstone carvers of Tabaka."

October 10.

Oas. J.P.

1988 "Codi ng, Anemion, and Planning: A Cap for

Every Head." In lndigCl/olls Cognition: Functioning ill

Cliitumi COlI/eXI, ed ited by 1.W. Berry, S.H . Irvine

and E.B. Hunt . Dordecht: Martinus Nijoff.

Eisemon, T.O., ct al.

1988 "Schoo ling for Self-Employment in Kenya:

The Acquisition of Craft Skills in and olltside

Schoo ls." Internatiollal Journal of Educational

Development 8, no. 4: 271-8.

Esbin, H.B.

199 1 "Wes tern Aes the tic Convelllio ns and

Artisanal Produdion in Non-Western Cultures."

Unpublished master's thesis. McGill Uni versity.

Fisher, J .L

1966 "Art Styles as Cultural Cognitive Maps." In

Alltllrop% B)' alld Art: Readings ill Cross-ClllllIra/

Aesthetics, edit ed by C M. Ollen. Garden City:

Natural History Press.

Gamb le, T.J., and P. E. Ginsberg

198 1 " Di ffe renti at ion, Cognition, and Social

Evolution." Jou rnal ofCross-Clllluml PsycllOlo.qy 12.

no. 4: 445-59.

Graburn, N.

1976 Ethnic alld Tourisl Arts. Berkeley: Un ivers ity

of California Press.

Grampp, W.O.

1989 Pricing tile Priceless: Art, Artisls and EctJllomics.

New York: Basic Books.

Halano, G., and K. Inagak i

1996 "Two Courses of Expenise." In Child

Developmellt and Educatioll ill Japall . edi ted by

H. Stevenson et al. New York: W.H. Freeman.

J ules- Roselle, B.

1984 Til e Messages of Tourist Art. Ne w York:

Pl enum Press.

LeVine, R.A., and B.B. LeV ine

1966 Nya l/sollgo: A Gusii Colmmmiry ill Kenya. New

York: J ohn Wiley & Sons.

Maq lleL J.

19 86 Th e Aesthetic Experience. New Haven. CT:

Yale Uni versil Y Press, Nairobi.

Maranga, l.S.

1987 "Schooling, Cog nit ion and Work: A Study

of Cogn itive Aspecls of Stone-Carving." Paper

presen ted at the Bureau of Educat ional Research,

Nairobi.

Mudimbe, V.Y.

1988 Tile 11Ivemioll of Africa: Gellesis, PhilosopJlyalld

the Order of Kllowledge. London: James Currey.

Dchieng, W.R.

1974 A Pre-Colonial History of the Gusii of Westem

Kw)'a c, 1500- 19 /4. Kam pala: East Afri ca n

Literature Bureau.

Perkins. D.

1977" A Beller World: Studies of Poetry Editing."

In TIle Arls fl!ul Cogl/ilion, ed ited b y D. Perkins.

Balt imore: Johns Hopk ins Press.

Price, S.

19 89 Primitive Art ill Civilized P/aees. Ch icago:

University of Chi cago Press.

Richter, D.

1981 Art, Ecol/omies, a/ld Change: The Kiliebele of

Nonllerll Ivory Coast. LaJo lla: Psych / Graphic

Publi shers.

Sinatra, R.

1986 Visllal Literacy Connecrions to Tllillkillg, Rradil/g,

aud Writil/g. Springfield: Charles C Thomas_

Sykes, J .B.

1985 The Collcise Oxford Dictiollary of Cllrrellt English.

Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Vygotsky, L.S.

1987 "Think ing and Speech. " In L.S. Vygotsky,

Coffected Works, Vol. I, edit ed by R. Richer and

A. Canon, New York: Plenum.

1981a "The Genes is of Higher Mental FunL1ions."

In Tile COl/cept of Actipity ill Soviet Psychology, ed ited

by J. v, WeClsch. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

1981b "The In strum ent al Method in Psycho log y." In The COllcept of Actil'ity ill Soviet Psychology,

ediled by J.V. Wertsch. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

1978 Mind ill Sodety: Ti,e Developmem of Higher

Psycl/Ological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

Un ivers it y Press.

Whit ing, B.B.

1963 Six ClIlllires, Studies of Child Rearillg. New

York : Wiley.

Holland, D., and N. Quinn

1987 "I nt roduction: Culture and Cognition."

In Cil/lural Models ill Lallguage alld Tllol/glrt.

edited by D. Holland and N. Quinn. Cambridge:

Camb ridge University Press.

John -Steiner, V.

1985 Notebooks of tlte Milld . Albuquerqu e:

Un iverS it y of New Mexico Press.

14

Vol. 15. No . I Sprill9 2000

t

CO NTEMPORARY lNUIT AND N ORTHWEST COA ST FINE ART

The #1 Inuit label in North America

TN TORONTO, 41 6- 922- 3448

800-435 - 1046

HO URS BY APPOINTMENT

1~'/1Jl!J($Jl'JJ5l( ~O!tf!DS

Supplying you with Inuit music from

Traditional to Contemporary.

P.O. BOX 286, Inukjuak, Nunavik

Quebec, Canada JOM 1MO

Tel : (819) 254-8788 Fax: (819) 254-8 113

www.inukshukproductions.ca

E-mail : info@inukshukproductions.ca

ART SPACE

G

A

L

L

E

R

Y

• COLLEC TIONS CONSULTANT

• EXHIBITIONS

• MUSEUM EDUCATION

• ART TOURS

Dealer Inquiries Welcome

PRESEN TING A NATIVE PERSPEC TIVE THRO UG H THE ARTS

15

Foe U 5

Focus On:

CURATORIAL COLLABORATION

For over a decade, the natllre of mratorial practice in Canada has been undergoillg c/wllenge and turmoil as cultural

museum workers struggle to deal with the increasing First Nations insistence on being included ill their own representati"on

in exhibitions and museum displays. Collaboration and consultation with the concerned communities, once rare in the

IIIl1seUIII world, have becollle a critical part of the exhibition development process, althollgh still controversial alld often

difficult to negotiate. The following article by Dorothy Speak provides a background for the current revolution in mratorial

practice, which will be explored ill a series of case studies highlighting the practical and innovative sollltions reached

by curatorial teams to ensure accurate represelltation and meaningful community inptll. In this, part one,

Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC) curator Judy Hall and Baker Lake gallery owner Sally Qilllllliu'lIaaq Webster

disalss their experiences collaborating 011 Sanatujut: Pride in Women 's Work, tile Inuit component of the 1995 CMC

exhibition Threads of the Land: Clothing Traditions from Three Indigenous Cultures.

I. Introduction

By Dorothy Speak

l is now more than a decade since

the Lubicon Lake Band of Cree boy·

COiled The Spirit Sillgs, an exhibition

of Indi an and Inuit artifacts at th e

Glenbow Museum in Calgary. The

exhibition sponsor. Shell Oil, was leasing

Lub icon land from th e Alberta government , resulting in disruption of the

band's livelihood. The band objected to

Glenbow's use of Shell money to mount

a show claiming to ce lebrate the richness of traditional Cree culture while

ignoring present realities. Although many

international institutions, in response to

the Lubicon lobby, declined to lend works

for the ex hibition or to host it, the show

went on as planned. Subsequent requests,

ignored by Glenbow, that certain sacred

16

objects be removed from the exh ibi tion

raised the thorny issue of repatriation

and pointed to the need for institutions to

co ll abora te with subject communities in

the conceptualization, plaruting, research

and mounting of exhib iti ons of ethnic

mater ial. The Lubicon protest was a landmark event for Canadian cultural institutions, raising awareness of the need

for sweeping changes in museum policy and practice w ith respect to the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples and

that of other minority groups held in

public collections.

The cris is at Glenbow was followed

two years later by the controversial illto

Ihe Hearl of Africa at the Royal Ontario

Museum (ROM) in Toronto. This exhibition, which set out to examine Canadian participation, both as British soldiers

and as mi SS ionaries, in the coloni zation

of Africa, led to somet imes vio lent

protests by the nedgling Coalition for

th e Truth about Africa. This group

accused the exhibition organizers of the

very racism the show purported to expose.

Though the ROM had, in developing the

exhibition, held focus-group meetings

(0 gauge the reaction of members of the

black commun ity to the material, the

breadth and depth of consultation were

clearly superficial. pointing to an imperative to form genuine and equa l partnerships with subject commun iti es from the

very moment an exhibition is conceived.

Of course, these precise issues of owner~

ship and interpretation of cultural properties had for decades been percolating in

minority and indigenous rultures around

Lhe world, from Amerindians to the Australi an Maoris to South Africa's blacks. In

the United States, the growth of political

awareness among American Indians preceded politicization of Canadian First

Peoples and event uall y had repercussions

here. Fo llowing th e In dian Awareness

Vol. 15. No. / Spring 2000

\ IN WHOSE

INT£Kr~1'

~'E~"rlfr

movement of the 1960s in the United

ItlT

States, Indian people enrolled in

unprecedented numbers in colleges and

universities, choosing Indian topics as

their subject matter. This focus led them

naturally to museums, the repositories

of Indian cultwa l material. Indians began

to protest exhibition of their ancestors'

remains and sacred objects, eventually

demanding return of such items to their

places of origin.

Calls around the world for repatria·

tion of human remains, the first and most

fundamental of the demands, were ini ·

tially met with shock and sometimes with

obstruction by museum professionals.

who until then had considered themselves

the allies of indigenous peoples. The

religious imperative behind the request

was the central belief that disturbing

the dead interferes with their afterlife.

Furthermore, public display of human

remains was considered a humiliation.

Chief among the arguments by

Once repatriation of human remains

museum officials against repatriation of

human remains was loss of material had been brought to the fore, it was only

va luab le for historical, biological and natural for indigenous peoples to begin

medical research of benefit to all sod· to demand the return of sacred objects, an

eties. However. considering the nature of area far more complex than that of the

contemporary global communications and ske leta l remains because of questions of

the sophistication of modern imaging definition. 11 can be argued, for example,

technology and information storage, it that most traditional material has, to

has been increas ingly recognized that some degree, sacred or spiritual power

possession of the object is far less impor- simply by virtue of the energy and feeling

tant than access to data about it. In the invested in it. in addition to sacred objeas.

meantime, many governments have return of objects fundamental to cultural

passed legislation with respect to repa· patrimony or objects taken from graves

triation of skeletal remains, some strin· began to be discus se d. When housed

gently requiring it, others (such as in in museums, these artifacts are, in the

Australia and Canada) recognizing the view of some Natives, "hel d in exile and

claims and interests of both the sci en· denied their intended role within the

tifi c and the indigenous communities, communi ty" (Crop Eared Wolf 1997, 38).

It was also pointed out thai man y

encouraging tolerance and cooperatio n

in resolution of th e disputes and recom· Native objects were illegally or uncthi·

mending that the future of collections cally acquired. Ln Canada, onc of the most

be determined in partnership, rather than famous cases of this was confiscation by

federal agents in 1921-22 of Kwakiutl

imposed by one group upon another.

Potlatch ceremonial materials. First

Nations began to ins ist that objects form·

ing the foundation of Native cultural

identity should be returned to their

Alvin Wandering spirit

protests the Glenbow

Museum exhibition

The Spirit Sings,

Calgary, 1988.

<r-<:'

~<l')"VA~\'

places of ori gin because their return

would re·e stablish vital co nnections

between First Peop les an d thei r pas!. In

th e words of one Native spokesperson,

''There are objects in museums which we

require to awaken us" (Tivy 1993,27) .

Again, demands for repatriation were

resisted by some museum s defending

their obligation to hold co llections in

trust for all citizens. For awhile, the word

"repatriation" struck fear into museum

officials, who were concerned that all

kinds of objeds would be claimed, leaving

the collect ions compromi sed or depleted

and the educational mission of museums

undermined. This, of cou rse, has not

tTanspiJed.

17

Gradually, through discu ss ion a nd

negotiation, many museums have tried to

undertake a fund amental shift in philosophy with resp ect to ownership, ethics

and social responsibility to First Peoples

and their cultural heritage. Among these

p rofess ion als, many have di scove red

unexpected benefits in the repatriation

process. Stronger ethical rel ationships

with First Peoples, a deep er understanding of mu se um collections and the

values that make the relevant objects

meaningful to Firs t Peoples, and new

partnerships with Native groups in the

attemp t to int erpret and preserve the

objects are chief among th e gains. They

are all considered Lo be of far greater vaJue

than act ua l p ossess ion of th e objects

themse lves.

The 1988 prot ests in Canada against

The Spirit Sings led to the formation of the

Task Force on Museums and First Peoples.

It s repor t, re leased in 1992, ca lled for

three changes: in creased involvement of

Aboriginal peopl es in the interpreta tion

of th eir cuJlures in exhibitions; improved

access by Aboriginals to collections; and

rep a triation of a rrifacrs and human

remains. Canadian museums have looked

wi th mix ed success to the repoT! as a

framework for chang es in philosophy

and practice with respect to Abori g inals

and the int erpretation of their hi stories.

Since then , some institution s hav e

taken steps to esta blis h form al links

with First Nations groups. At Gl enbow

Museum, for inst ance, a First Nations

Advisory Council was form ed in 1990

to advise the museum on the collection,

care and handling of Native materi als,

appropriate mar keting of im ages and

development of exhibitions. Council members also act as reso urces for researchers

and liaisons wilh Native communities. A

First Nations Policy outlines avenues of

coopera tion. Gl enbow also has an active

program of lend ing sacred materi al to

18

originalOrs. A First Na tions person has

been appointed 10 th e muse um 's board

and staffing pra cti ces place a grea ter

emphasis on moving towards ethnic

div ersit y. Glenbow's co mmitm en t is

d es igned to ensure a strong and deep ly

entren ched poli cy of co nsultation and

collaboration with First Nations p eopl es.

Methods by which museums con ce ive

of and mount exhibitions ha ve been a

centra l issue of reform. Some museums

have begun to recognize the import an ce

of emering into partn ers hips with communiti es at the very inception of an ex hibition. Attempts at co llaboration have

revea led fundamental differences in th e

way First Peoples and traditionally objectoriented museums view cuJrural artifacts.

Says Roy Wagner in Tlte 11lvemiofl of Culture, "Our attempts to metamOlphize tribal

peopl es as 'culture' have reduced them 10

techniqu e and artifact" ( 198t, 29). For

their part, indigenous peoples object to

b ei ng seen as "a nthropological speci me ns ," their cultural heritage frozen

in the past rather than cominuous and

living and their patrimony held in trust

and explained by their fonner colonizers.

Th ey are insist ing more and more th at

th ey be recognized an d co nsult ed as

exp e rts on their own culture. Th ese

dem ands are of course much strong er

among Aboriginal socie ties livin g in

geographic proximity to museum s and

their audiences than, for instance, among

th e Canadian Inuit, who live in greater

isolation.

Museums and crnators are being urged