207 Queen's Quay West, Toronto, Canada M5J 1A7

Tel & Fax: 416.603.7591

da vi d@HarrislnuitGallery.com

www.HarrislnuitGaUery.com

www.HarrislnuitGallery.com

CANADA'S FIRST LIVE CAMERA INUIT ART WEBSITE

INUIT

ART

QUARTERLY

04 1

At the

Galleries

Winter 2006 Vol. 21 , No.4

EDITOR: Marybelle Mitchel l

ASSISTANT

EDITOR: Mi riam Dewar

INUKTITUT

TRANSLATION: Mishak Allurut

ADVERTISING SALES: Anna Burnstei n

CIRCULATION: Tania Budge ll

DESIGN AND

TYPOGRAPHY: Acart Communications Inc.

PRINTING: St. Joseph Print Group

PUBLISHER: Inui t Art Foundation

EDITORIAL

ADVISORY

COMMITTEE

2005- 2006:

Mattiusi lyaituk

Shi rley Moorhouse

Melanie Scott

Norman Vorano

Ways of Thinking About Inuit Art:

Sharing Power / Marybelle Mitchell

DIRECTORS, Gayle Gwben

INUIT ART Mattiusi Iyaituk

FOUNDATION: Paul Malliki

Shirley Moorhouse

Mathew Nuqingaq

Nuna Parr

Okpi k Pitseolak

John Terriak

All rights reserved. Rcproduction without written

pcrmission of the publisher is strictly forbidden.

Not responsible for unsulicited materiaL The

vicws expressed in Inuit Art Quarterl)' are not

necessarily those of the editor or the board uf

directors. Feature articles 3re refereed. IAQ is a

mcmber of Magazincs Canada. We acknowledge

the financial suPPOrt of the Government of

Canada, through the Publicat ions Assistance

Program (PAP) towards our mailing costs, and

through a grant from the Department of Indian

and Northcrn Affairs Canada. PAP number

8986. Publications mail agrecmcnt number

5049814. Publication d;Jtc of this issue:

Novembcr 2006. ISSN 0831-6708.

Send address changes, letters to the editor

and advertising enquiries to:

lnuit Art Quarterly

2081 Merivale Road

Ottawa, Ontario K2G IG9

TeL (6t3) 124-8189; Fa" (6t3) 124-2907

e-mail: iaq@inuitarr.org

website: www.inuitan.org

Subscription rates (one year)

In Canada: $31.75 CST incl.,

except NF, NS, NB, QC residents: $34.15

(GST registration no_ RI21033724)

Unired States: US$30

Foreign: US$59

C heque, money order, Visa, MasterCard and

American Express accepted.

Ch:lrirable registration number: 121033724 RROCOI

2

I

VOL . 21,

N O. 4

WINTER

08 I EDITORIAL ESSAY

2006

The pmitioning of Inuit and their art in public

galleries has gone through dramatic changes in

the last two decades, but there is still much

to accomplish.

18 I FEATURE

Silver and

Stone: The Art

of Michael

Massie / Gloria

Hickey

Michael Massie's

first curated solo

exhibition at The

Rooms Provincial

Art Gallery in

St. John's,

Newfoundland.

This article recaps

10 years of hIS

career from 1996

to 2006, with

a foc us on the

transformative

nature of his art.

34 I FEATURE UPDATE

36 I UPDATE/BRIEFLY NOTED

Great Northern Arts Festival seeking new

direction . Canadian government suspends

artist infonnation fn-ogram ..

39 I IN MEMORIAM

Aoudla Pudlat (195 1- 2006)

42 I LETTERS

47 I ADVERTISER INDEX /MAP

1nuil Arl Quarlerly is a publicotion of the Inuit Art Foundonon, anon-profit organization governed by aboard of Inuil artist. The foundolion's mission is 10 assist

Inuil in the developmenl of their professional skills and Ihe morkenng of their orl

and 10 promole Inuil orl Ihrough exhibif5, publicolions and films. The foundolion

is funded by conlribunons from Ihe Deporlmenl of Indian and Northern Affairs

Canada and olher public and privole agencies, as well as privole dononons by

individuals. Wherever possible, iloperoles on acost recovery basis.

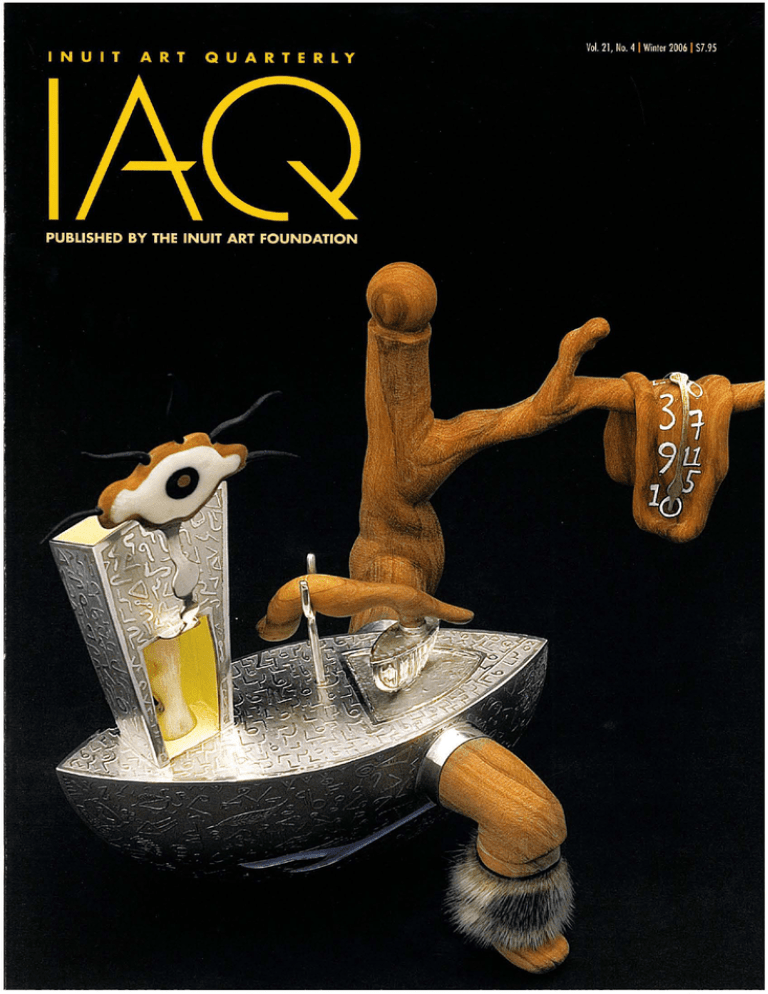

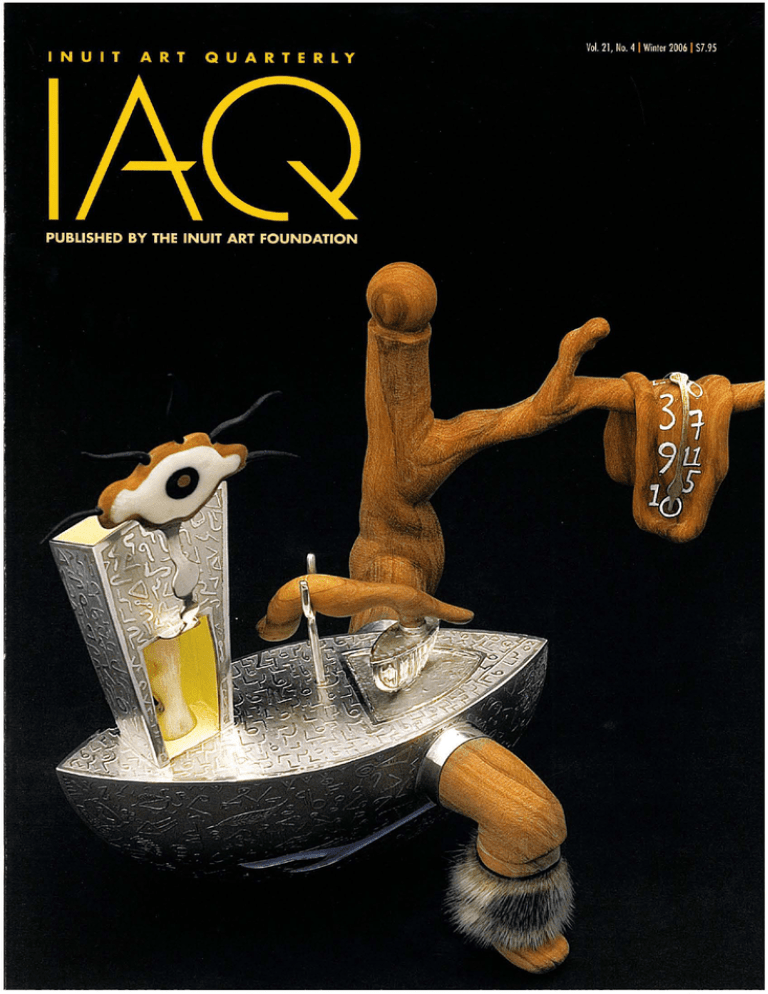

Cover Image:

enigmas of a teapot, 2002, Michael Mossie, Kippens (etched sterling

silver, olive wood, horse hoir, muskox horn, ebony, ivory, seal skin,

enamel and sinew; 19.68 x 24.13 x 14 .22; private collection), See

page 27 For Massie's explanation of this piece. Ltd Lr', - PA

L

\

a-I>{'''L ..

30 I REVIEWS

Annie Pootoogook at the Power

Plant Contemporary Art Gallery

I

Reviewed by Marshall Webb

Annie Pootoogook's groundbreaking

exhibition at the Power Plant

Contern/Jomry Art Gallery presents a

startlingly different image of the North.

INUIT

ART

QUARTERLY

I

3

A T

THE

GA

L

LER

E S

-.

Antler into Art, an exhibition of bone work at

The Winnipeg Art Gallery from December 22,

2006 to Aprit 22, 2007, shows the different

ways that artists use antier to create widely

varying subjects. Shown: Drumdance, 1971 ,

Luke Iksiktaaryuk, Baker Lake.

Nuvisavik: The Place Where We Weave, a travelling exhibition of tapestries organized by the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 2004,

at the McCord Museum from November 4, 2006 to March 25, 2007.

Shown: Inuit Ways, 1979, woven by Olassie Akulukjuak (from an image

by Eleesapee Ishulutaq), Pangnirtung.

Pub Ie

Go erles

•

•

Cerny Inuit Collection presents Shared Arctic, an exhibition of artwork from the circumpolar North from September 6 to

December 6, 2006 in the entrance hall of UBS offices in Paradeplatz, Zurich, Switzerland. Shown: Untitled [Inuk Fishing} and

Untitled [Inuk}, c. 1970, David Kavik, Sanikiluaq.

A

I

VOl . 21 ,

NO . 4

W I NTER

2006

Life Near Gjoa Haven, an exhibition of three Inuit fabric artists

(Jessie Kernek, Martha Koguik

and Bessie Nahalolik) organized

by the Alberta Society of

Artists with artworks borrowed

frorn the City of Calgary Civic Art

Collection, tours through rnultiple

schools, community libraries,

and art centres in southern

Alberta from September 2006

to June 2007. Shown: Winter,

1983, Martha Koguik.

& Commercial

Galleries

From November 19 to December 23, 2006,

Canadian Arctic Gallery in Basel , Switzerland

presents MastelWorks V featuring new sculptures

from artists such as Keogak Ashoona, Axangajuk

Shaa, Toonoo Sharky, Jutai Toonoo, Nuna Parr,

Adamie Ashevak, Luke Anowtalik, Robert and

Floyd Kuptana. Shown: Transformation, 2004 ,

Toonoo Sharky, Cape Dorset

Kipling Gallery in

Woodbridge, Ontario,

presents a solo exhibition of

work by Igloolik artist Bart

Hanna from November 8

to November 25, 2006.

Shown: Drummer, 2006.

Tapestries by Inuit Women: Artists from Baker Lake and Pangnirtung is at the

Canadian Guild of Crafts in Montreal from November 9 to December 30, 2006.

Shown: Snow Geese, 1995, woven by Kawtysie Kakee (from an image by

Andrew Qappik), Pangnirtung.

IN UIT

AR T

QUARTERLY

I

5

EXHIBITION DETAILS

Antler into Art, curaled by Darlene Wight, The

Winnipeg Art Gallery, 300 Memorial Boulevard,

Winnipeg, Manitoba. December 22, 2006 to

April 22, 2007. Telephone: (204) 786·6641.

The Brousseau Inuit Art Collection, curated

by Lyse Burgoyne-Brousseau and Raymond

Brousseau, Musee national des beaux-arts

du Quebec, Pare des Champs-de-Balaille,

1 avenue Wolfe-Montcalm, Quebec, Quebec.

Opens September 28, 2006. Telephone:

(416) 643·2150.

Kinngait: Highlights from the Collection, curated

by Karen Williamson, McMichael Canadian Art

Collection , Gallery 7, 10365 Islington Avenue ,

Kleinburg, Ontario. October 7, 2006 to

February 18, 2007. Telephone: 1·888·213·1121.

Saumik: James Houston's Legacy, curated by

Karen Williamson, McMichael Canadian Art

Collection, Gallery 9, 10365 Islington Avenue ,

Kleinburg, Ontario. February 10, 200710

January 27, 2008. Telephone: 1·888·213·1121.

Shared Arctic, organized by the Cerny Inuit

Collection. On display at UBS, Entrance Hall,

Paradeplatz 6, Zurich , Switzerland.

September 6 to December 6, 2006.

Telephone: +41313182820.

Eskimo and Inuit Carvings: Collecting Art from

the Arctic, at the Field Museum, Webber Gallery,

1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois.

July 1, 2006 to June 17, 2007. Telephone:

(866) 343·5303.

Archetypes in Stone, curaled by Maria von

Finckenslein, Canadian Museum of Civilization,

100 Laurier Street, Gatineau, Quebec. April 21 ,

2004 to December 31, 2006. Telephone:

(819) 776·8443.

Ufe Near Gjoa Haven, curated by Leslie Pinier,

organized by the Alberta Society of Artists

Touring various venues in Alberta: Millarville

Community Library in Millarville (October 11to

November 8, 2006); Stephie Wioma School in

Lake Sylvan (November 15 to December 13,

2006): Acme School in Acme (December 18,

2006 to January 24, 2007): Rocky Mountain

House in Rocky Mountain (January 29 to

February 26, 2007); and the Leighton Art

Centre in Calgary (March 5 to April 11, 2007).

Contact the Alberta Society of Artists for more

details. Telephone: (403) 2624669.

TRAVELLING EXHIBITIONS

Inuit Sculpture Now, curated by Christine

lalonde, organized by the National Gallery

of Canada. At the Surrey Art Gallery,

13750-88 Avenue, Surrey, British Columbia.

From November 18, 2006 to March 11 , 2007.

Telephone: (604) 501·5566.

6

I

VOL

21,

NO

.4

W I NTER

2006

In the Shadow of the Midnight Sun: Sami and

Inuit An (2000-2005) , curated by Jean Blodgett,

organized by the Art Gallery of Hamilton.

At The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery,

9 Bonaventure Avenue, St. John's,

Newfoundland. February 16 to April 20, 2007.

Telephone: (709) 757·8000.

ItuKiagatta! Inuit Sculpture from the Collection

of the TO Bank Financial Group, curated by

Christine Lalonde and Natalie Ribkoff, organized

by the National Gallery of Canada. On display

at the National Museum of the American Indian

(New York), The George Gustav Heye Center,

Alexander Hamilton, U.S. Custom House,

One Bowling Green, New York, New York.

November 11, 2006 to February 4, 2007.

Telephone: (212) 514·3700.

Our Land: Contemporary Art from the Arctic,

curated by John Grimes, organized by the

Peabody Essex Museum. On display at the

Institute of American Indian Arts Museum,

108 Cathedral Place , Santa Fe , New Mexico.

October 20, 2006 through February 4, 2007.

Telephone: (505) 424·2300.

Nuvisavik: The Place Where We Weave,

curated by Maria von Finckenstein, organized

by the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

On display at the McCord Museum,

690 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal,

Quebec. November 4,2006 to March 25, 2007.

Telephone: (514) 398·7100.

Arctic Spirit: Inuff Art from the Albrecht Collection

at the Heard Museum, curated by Ingo Hessel,

organized by the Heard Museum. On display at

the J Wayne Stark University Center Galleries,

Texas A&M University, College Station,

Texas , October 27, 2006 to January 7, 2007.

Telephone: (979) 845·8501 . At the Lowe Art

Museum, University of Miami, 1301 Stanford

Drive, Coral Gables, Florida from February 10

to April 1, 2007. Telephone: (305) 284·3535.

PERMANENT EXHIBITIONS

Ontario

Chedoke-McMaster Hospital (Hamilton)

Macdonald Stewart Art Centre (Guelph)

McMichael Canadian Art Collection

(Kleinburg)

National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa)

Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto)

Toronto-Dominion Gallery of Inuit Art

(Toronto)

Q uebec

Canadian Guild of Crafts (Montreal)

Canadian Museum of Civilization

(Gatineau)

McCord Museum of Canadian History

(Montreal)

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal)

Musee national des beaux-arts du Quebec

(Quebec)

Manitoba

Crafts Museum, Crafts Guild of Manitoba

(Winnipeg)

Eskimo Museum (Churchill)

Winnipeg Art Gallery (Winnipeg)

Nunavik

Pingualuil National Park Visitor's Centre

(KangiqsuJuaq)

Nu navut

Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum (tqaluit)

U nited States

Dennos Museum Center

(Traverse City, Michigan)

Alaska Museum of History and Art

(Anchorage, Alaska)

Correction :

In the article Metamorphosis: Eleven

Artists from Nunavik, Inuit Art Quarterly,

Vol. 21, No.3 [Fo il 2006) : pg . 34, 0

photo of Jobie Uqoituk from Inuk juak,

Nunavik, was incorrectly labelled

as Jackussie Ittukalluk . IAQ regrets the

error and apolog izes for any confus ion

this may have caused.

The Inuit Art Foundation:

20 years of helping artists

to help themselves'

Thank you for your support

PATRONS ($ 1,000 OR MORE)

Daniel & Martha Albrecht

Susan Carter

Joan A Martin

Dorot hy McCarthy

New Hampshire Charitable

Foundation Piscataqua Region

Nuna Parr

John & Joyce Price

ASSOCIATES ($500 - $999)

Margaret & Robert Jackson

Paul Maliki

SUPPORTERS ($ 100 - $499)

Gunther & Inge Abrahamson Fund

Argos Publishing

Irena & Peter Dixon

Elisapee Itulu

Drs Laurence & Katherine Jacobs

Charles C Kingsley

Holly M Stedman

Jean Stein

FRIENDS (Up to $99)

Bavin Glassworks

David Liebman

BEQUEST

The Virginia J Watt Trust

Inuit Art

FOVNDA10N

2081 Meriv"le Road

Ottawa, Ontario K2G I G9

Tel: (613) 224-8189

www.inuitart.org

iaf@inuitart.org

Arts Alive: Celebrating 20 years of IAQ

Canadian and American donors are

provided with tax receipts and all donations

are acknowledged in Inuit Art Quarterly.

Charitable registration #12103 3724 RROOOI

E

D

TOR

A

E

l

S

SAY

I

n my fall 1988 editorial, I reported a comment from

a reader who said she valued IAQ, not only for the information it provided, but also as a framework for organizing

thought about the subject of Inuit art. Although we may

miss activity in some sectors, I do think that most of the

issues animating the field have at least been broached in

the magazine: marketing; artists' preoccupations; women's

art; subject matter; quality; support mechanisms; and the

representation of Inuit artists in public galleries. As a

socio logist with a particular interest in the latter top ic,

I offer below an overview of what h as been published in

IAQ about the positioning of Inuit and their art in the

public galleries.

Ways of Thinking about Inuit Art:

SIIARING POWER

BY MARYBEllE MITCHEll

The Historical Representation

of Inuit Art in Public Galleries

There was great excitement in

Ottawa this year over the Narval

Morrisseau solo ex hibition at the

National Gallery of Canada (NGC).

Whi le this honour was a long time

coming for First Nations artists, a

few Inui t had already received the

di st inction of being presented at

the NGe Pudlo Pudlat in 1990

(see Inuit Art World, Fall/Winter

1990/9 [,81) and Marion Tuu'luq in

2002 (see Spring/Summer 2003:34).

Nonetheless, it is rare for Inuit work

to he shown in solo exhibitions and

much has been written in IAQ over

th e years about th e ambiguous status

of Canada's indigen ous arts.

In an article reviewing 50 years of

Inu it art exhibitions (Wimer 1997 3 ),

Maria von Finckenstein wrote: "The

hi story of Inu it art exhibitions in

public institutions is quite unusual.

Rather than the scho larly focus on

individual artists that characte rizes

mainstream exhibitions, Inu it art

has been mainly grouped in thematic

ex hibitions emphasizi ng pre~co nta c t

life." Moreover, cate ring to a more

8

I

VOl . 21 ,

NO . 4

WINTER

2006

popular audience, it is often the case

that Inuit ex h ib itions 3fe not professio nally cllrated and tend to focus

on old masters to the exclusion of

emergi ng talent. A further problem

noted by von Finckenste in (ibid. , 4)

is that "because many public collec~

tions afe the result of donations, a

large number of exhibitions feature

collectors' rather than curators'

choices." These factors have, she

observed, "prevented acceptance of

In uit art by mainstream art critics."

Further complicating the picture,

Inuit ex hibitions tend to be "more

promotional than scholarly" (editorial,

Spring 1997 ,6), which has the dual

effect of reinforcing academic snubbing and making it difficult for Inuit

to be taken se riously as artists.

In the very first issue of Inuit Art

Quarterly (Spr ing 1986J) , we ra n

an article enci tled "Is it Esk imo? Is

it Art?" refe rring to a conference of

the same t itl e held at the University

of Vermon t's Fleming Muse um in

Burlington. The question of au thenticity wou ld seem to have been put

to rest by the surprise announce ment

of the conference that the National

Gallery of Canada would be collecting Inuit art, starting with recent

gifts from well-known collectors

M.E Feheley, Dororhy Srillwell and

Virgin ia Watt. This represented, said

Inuit art curator Marie Routledge

(who had been seconded to the

NGe from the Department of Ind ian

Affairs and Northern Development),

"the first additions of contemporary

Inuit art to the galle ry's collection

since a 1984 revision of its acquisitions policy." Furthermore, she said

that "with the new policy, the gallery

affirms its commitment to collect the

work of Canadian Inuit artists and

thereby recognizes the importance and

quality of their work within the fabric

of contemporary Canadian art." I

The NGe's grudge aga inst Inuit

art was no secret in the commun ity.

In 1977, director Hsio-Yen Shih

called it "bingo art," referring to

it as art with no feeling (Summer

19885).' It took concerted efforts

over many years to overcome this

prejudice. Those famil iar \vith the

doings of the now defunct Canadian

Eskimo Arts Council knew that this

was a mission of some of its more

avid members, especially longtime

president Virginia Watt who told

me that they were finally able "to

make the gallery an offer it couldn't

refuse"- the offer being, of course,

staff seconded from OlAND (Marie

Routledge) and sign ificant donations

of artwork.

The unequivocal language

of Routledge's 1986 Burlington

announcement appeared to be a

giant step forwards fo r Inuit art,

but the same old question as to

whether or not Inuit art is worthy

to be considered in the same breath

as "real" art continued to raise its

he<1d. The summer 1986 issue of

Inuit Art Quarterly carried a conversation ("Folk art? Fine art?") between

Terry Ryan and Sharon van Raalte,

Inuit art spec ialists, and Rudolf

Arnheim, a distinguished American

historian of western art. And,

although it was reported (Spring

1988:23) rhat the opening of Canada's

new nation<11 gal lery "marked the

first time that an exhib ition of contemporary Inuit art has been featured

as part of the Nat ional Gallery's

permanent collection," Dorothy Speak

wrote a critical article for IAQ

entitled "It's Inu it. Where do you

put itl" echoing the theme of the

1985 conference organized by the

Canadian Museums Assoc iation:

"It's Native: Where Do You Put It?"

(Summer 1988:4).

perusal of lAQ's "Calendar of Events"

from 1986 onwards. The McMichael

Canad ian Collection (under the tutelage of Jean Blodgett), The Winnipeg

An Gallery (Jean Blodgett, followed by Darlene W ight), rhe

Inuit exhibitions tend to be more promotional

than scholarly, which has the dual effect of

reinforcing academic snubbing and making it

difficult for Inuit to be taken seriously as artists

Predictably, compla ints were made

as to the second rate nature of the

space accorded Inuit art in the gallery's

new quarters, which opened in 1988.

At first, it was displayed in what

appeared to be a corridor, as described

by Speak (ibid., 4). The gallery's

explanation was that the last minute

incl usion of an Inuit art exhib ition

space could not be incorporated in to

the design process. Speak's conclusion

was that "the physical separation

of Inui t art in the new gallery can

only perpetuate the perception that

Inuit artists are different from other

Canadian artists ... and that their

art must be assessed within a special

ethnographic context" (ibid., 5) .

In February 1993, Inuit art was

moved to the lower level of the

gallery, to what had been set aside

as a storage area.

Apart from the connotations of

the space allocated to Inuit art in

Canada's national gallery (as many

point out, it is in the basement),

Inuit art continued to occupy a

peripheral role in Canadian art history, ignored not just by the NGC,

but also by the Royal Ontario Museum

(ROM) and the An Gallery of

Ontario (AGO). The ROM, for

instance, had begun "to accept Inuit

sculpture as donations" in the mid1950s and early-l960s, "but did not

purchase it" (Nelson Graburn, Fall

1986:5). By [he late 1980s, however,

Maria von Finckenstein noted that

"Inuit exhibitions were showing a

clear trend from early government

and commercial involvement to an

increasingly active interest among

public galleries" (Wimer 1997:7).

Her observation is supported by a

Canadian Museum of Civilization

(Odette Leroux, followed by von

Finckenstein), and the McDonald

Stewart Gallery at the University

of Guelph (Judith Nasby) were

active in the collecting of, exhibiting

of, and writing about Inuit art , and

in December 2005, the ROM opened

a permanent space devoted to the art

and culture of Canada's Aboriginal

peoples (Spring 2006:32). Aboriginal

advisors were engaged to help select

and label artifacts from the museum's

extens ive collection.

The Art Gallery of Ontario

(AGO) "came on board" in the

1980s (von Finckenstein, Winter

1997:7) and, in larrer years, has

accepted the donation of thousands

of works of art from the Klamer Family

and Esther and Sam Smick. Although

it now has "one of the finest private

collections of contemporary Inuit art

in the world" (Speak, Inuit An World

Fall/Winter 1990/9l:6l), the AGO

continues to have an ambivalent

attitude towards the art,

ev idenced

in the fact that, except for a brief

period in the early 1990s, it has

employed no curator of Inuit art and

organizes few exhibitions. The gallery

did, howeve r, make a decision in

2002 to display Aboriginal art with

European and Canadian art from the

same period. In that year also, the

NGC made a dec ision to display

Native wo rk chronologically, geo~

graphically and thema tically with

orher works (Summer 2002:5) .

Along with The Winnipeg Art

Gallery, which is in a league of its

own, the Canadian Museum of

Civilization (CMC) has been probably

the least ambivalent about the merits

of collecting Inuit art, especially

a"

INUIT

ART

QUARTERLY

I

9

during the watch of Bill Taylor.

Taylor was an emhusiastic su pponer

who nO[ only expanded the collection

but also created a curatorial position

to oversee it (first filled by Odette

Leroux, who WrlS succeeded by Maria

von Finckenstein, who, in turn, has

bee n repl aced by Norman Vorano

[fall 2005]) . The CMC started

co ll ecting sculpture in 1953 and purchases continued on an annual basis

the reafter until the mid-1990s. A

museum, as opposed to an an gallery,

the CMC did not have co concern

itself with western aesthet ic hierarchies, but could celebrdtc the cul turdl

heritage of Canada's First Peoples,

{)nistic or otherwise. In its new quarters, opened in 1989, 3,CXXJ square fee t

were dedicated to rotating displays

of Inuit work, a move celebrated by

Doroth y Speak in an IAQ article entitled "A Collection Without Parallel

Scesthe Light of Day" (Fall 1989,4).

Inuit Art Abroad

While most of the controversy simmers within Canad ian borders, Inuit

art has been met in recent years with

a varied but mostly den igrated recepr.ion overseas, as we discovered while

do ing research for our Inuit Arc World

issue: "Many European museums have

Eskimo holdings," we concluded, "but

they me treated as eth nographic

mate rial and the contemporary art

form is overlooked." Indeed, th e

editor of a German art magazine

"flatly to ld o ur researcher that he

would nOt consider cove ring Inuit

art as a contem po rary art form"

(Fall/Winter 1990/9 \' 9).

Interesti ngly, however, Norman

Vorano makes the point that it was a

1953 exhibition at Gi mpel Fils Gallery

in London, England that "marked the

moment the international art world

awakened to the aesthet ic poss ibilities

of Inuit ert" (Fall/Winter 2004,10).

Apart from The Winnipeg Art Gallery,

which is in a league of its own, the Canadian

Museum of Civilization has been the least

ambivalent about the merits of collecting

Inuit art, especially during the watch of Bill

Taylor, an enthusiastic supporter who not only

expanded the collection but also created

a curatorial position to oversee it

Unfortunately, the slash ing of

museum budgets across th e country

means that Inuit art is no longer

front and centre at Canada's national

muse um. The large space used exclusively for ex hi bitions of Inuit and

First Nat ions arts has, wi thin the

last five years, been usurped for other

purposes and the permanent displays

of Inuit art arc now contained in

glass cases in a lower corridor and in

a few display cases in the history hall.

Some Inui t work has, of course, been

included in the First Peoples Hall,

which opened in January of 2003,

and the museum does contin ue to

Illount important tempora ry exh ibitions, such as Nuvisavik: The Place

Where We Weave (2002-03) , es well

as play host co travelling exhibitions.

10

I

VOl . 21,

NO . 4

WINTER

Vorano refers to Virginia Watt's

statemen t (!989A2-3) that it was

because of the "extraordinary cri tical

acclaim" it received on this occasion

that th e Canadia n Govern ment

undertook a vigorous campaign to

promote Inuit art abroad (Fall!

Winter 2004,10).

Iron ica ll y, wh ile the G impel Fils

exhi bition "put Inuit art on the map

of world arts . .. thar map has since

changed and continues [0 do so."

T he dem ise of "primitive-modem ism"

as the dominant critical strategy in

the art world has giv en many promotional endeavours for Inui t art

an an tiquated look. In terms of promotion, few artists are capi tali zing on

what Vorano refers to as "the present

moment ... of ope nness [in the

2006

internat.ional art world). As he says,

"wh ereas, in the past, critics sought

o ut the singu lar, 'authentic' and pure,

they now search fo r the multiple,

syncretic and h yb rid'" (Fall/Winter

2004,14).

There arc some successful marketing ve ntures in Europe and there

have been some exhibitions of nore,

especially Sculpture/Inui t organized

by the Canadian Eskimo Arts Counc il

in 1971. Living Arcric; Huncers of the

Canadian North, a 1988 exhib ition

fOCUSSi ng on the people rather than

the art, attracted much attention in

London. Nelso n Graburn and Mo ll y

Lee noted the enthusiasm for this

exhibition, which had been organized

by Ind igenous Surv ivall ntemat ional ,

as a forum for the Native side of the

worldwide struggle between hunting

and an imal rights (Fall 1988, I0).

Impressed with the Native

involvement in organizing Living

Araic, Graburn and Lee titled their

rev iew: "The Li ving Arcti c: Doing

what the Spirit Sings Didn't," a reference to an exh ibition of Canadian

Indian art organized by th e Glenbow

Museum in Calgary in 1988, wh ich,

along with Into the Heart of Africa at

the Royal Onta ri o Museum in 1989,

has entered definitively into the

annals of museu m h istory. Both

provoked widespread and vigorous

protests among thei r subject peoples.

In the case of The Spirit Sings,

the Lubicon C ree~q lli c kt y joined

by mher Native and non -Native

groups-protested the Glenbow's pur~

port ing "to show the richness of th e

early contact cul ture, using money

from Shell Oil," onc of the companies

encroaching on what they considered

to be Lubicon territory, bulldozing

gravesites and interfering with hunting

and trapping (Winter 1988, 12). O ther

issues were raised in what became

a wider protesting of museum policies

v is-a~v is indigenous peoples and their

material culture: repa triat ion, the

display of sacred objects, and the

representation of Native peoples

in museums and ga lleries.

Protest Provokes Change

The result of the Lubicon Cree

protest of The S,)iril. Sings was th e

establishment by the Canadian

Mu se um Association (CMA) and

the Assembly of First Nations (AFN)

of a Task Force on Museums and First

Peoples to address areas of confl ict

(Spring 1990049). In an article entitled "Preserv ing our Heritage: Getting

Beyond Boycotts & Demonstrations"

(Winter 1989: 12), anthropologists

Valda Blu ndell and Laurence Grant

wrote about a co nference of the

same title orga ni zed by the AFN

and the C MA and held at C arleton

Univers ity in November 1988.

A lthough they concluded their piece

with an expression of confidence that

the conference could "set initiatives

in motion that will bring aoout new

relations between Native Canad ians

and this country's cultural institutions," they acknowledged that such

an optimistic outcome depended

upon the Nati ve people having

"a real voice in po licy formation"

(ibid., 16)-'

With some help, the Lubicon,

a small First N at io ns band in

north -central Alberta, succeeded

in gene rating a major sh ift in how

cu rators and academ ics think about

what they do. Invited to write about

teaching the anthropology of art

for our speciall nuir Art World issue

(Fall/Winter 1990/9 101 00), Blundell

wrote that "through their art forms

and their understandings of their

an mak ing, Ind ian and Inui t artists

are now playing a crucia l role in

raising concerns aoout their portrayal

by 'academ ics.'"

Still, while acade mi cs are sensitized

to the need for inclusion, it would

seem thac not much has changed in

terms of university-level courses of

study ded icaced to Native ans. lAQ's

survey in 1990 of 32 Canadian and

America n un iversit ies revea led that

few courses specifically addressed

Inui t art or the art of any of Canada 's

indigenous peoples and "when courses

are offered, they are typ ically included

in 'Native studies' programs rather

than in art hi story or visual ans

faculties" (Fall/Winter 1990/9 U 04).

At a workshop a dec;)de and a

half late r, art historian Jean Blodgett

declared that "Inuit art continues

to function on the periphery of the

establishment" (Fall 2003 047) . She

gave three reasons fo r thi s sidelining

of In uit art: "It is difficult to fit it

into western art history; there are

questions {still] of its authenticity; and

it does not operate on an intell ectual

leve l that is appea li ng to practitioners

of contemporary art cri tic ism."

Norman Vorano also addressed

the issue of In uit art's sta tus within

academe in a very recent issue

(Fall 2006, 18). Taking up Janet Berlo's

po int that the study of Inui t art

is "only in its ea rly adolesce nce,"

Vorano noted that it has nor

attracted much interest from graduate students, nor from wi thin the

discipline of art history (most scholars

hold only an MA or come from other

di sciplines ). "A s a fi eld," he wro te ,

"Inui t art has bee n and co ntinues

to be overwh elmingly do minated

by n on~ lnui t specialists ta lk ing and

writing about Inui t people, wh ich

compares un favo urab ly with First

Natio ns people who "are now [more

than ever] writing [their own} art history and critical discourse" (ibid., 20).4

lsumavul worked with lead curator

O dette Leroux from its conceptual

beginning in late 1990. Leroux

expanded the curatoria l team to

include Minni e Aodla Free man

and Marne Jackson, as we ll as twO

other Inuit women as adv iso rs and

interpreters (Sp ring 1995 :26 ).

The art ists were at first reticent

to write about themselves: "We

have always bee n written about,"

they said (1997, 16). Consu ltant

Minnie Freeman, herself an Inuk,

praised curator Leroux who, she said,

"didn't pu t he rself in the front, .

she made other people be in front,

and I think that's why she got so far

beyond the source of Inuit women's

feelings as they wrote about them."

Th is sen timent was seconded by

artist Pitaloosie Saila who expressed

her gratitude that Ode tte Leroux

had met with the women artists in

We can count on the fingers of one hand,

the curators/writers who have had most

influence in determining what will be

signified as worthy Inuit art .. . At this time,

no Inuit names can be added to this roster

Struggling to Reconcile

Inclusiveness with Professionalism

Wh ile we would like to think that

"the qu estion is no longer should we

include Abori ginal art in art history,

but how do we do tha t ?" (Fall

2003:47) , acade mi cs are struggling

to find ways to be inclusive with ou t

undermining or watering down the

standard s of museology upon which

their professional reputations rest.

It is interest ing to note that the

C anadian Museum of Ci vilizat ion,

that unabashed collector of Inui t

art, has again led the way wi th

two ex hibitions that are now the

best models we have for how to

collaborate with Inuit; Isumavut:

The Artisric Expression of Nine Cape

Dorset Women (October 1994 to

March 1996) and Threads of the

Land: Clothing TradItions from Three

/ruligenous Cultures (1995)5

Consulted about their work and

invited to wri te stories for publicati on,

the seven livi ng women presented in

the planning stages: "The more they

[Leroux and Minnie Freemanl talked

about the planning of the ex hibiti on ,

the more excited I got, beca use they

involved us in the planning too."

IAQ's review of Isumavut dealt

not only with the artwork , the co l ~

laborat ive model and the resulting

publication but also with a rev iew

in Toronto's G/obe & Mail. In

"An Exhib ition, a Book and an

Exaggerated React ion" (Spri ng

1995:26), our rev iewer, Janet Berlo,

took exception to comments that the

quality of the exhibition had been

compromised by the inclusion of

the art ists in the curatorial decis i o n~

making process. Berlo cou ntered that

it is "routine practice in every art

gallery and muse um in Europe and

North America for a li ving artist to

be consu lted when a retrospective

exh ibit is hun g" and "no one

ever suggests that the curator of

20th century art is abroga ting

curatorial responsibility when such

IN UI T

ART

QUARTERLY

I

11

consultati on takes place" (ibid., 35).

Go ing further, she concl uded: "The

"In spite of all that

has been said and

promised, Native

North American arts

remain marginalized

in public art galleries

[although they are]

increasingly visible

in anthropological

museums, cultural

centres and

commercial galleries"

- Lynda Jessup

world of In uit art studies has for a

long t ime been its own insu lar litde

domain, somewhat removed from

th e intell ectua l issues that have ani mated sc holarship in other areas of

Nat ive arts over the last two gene rations." Fo r that reason , "as a sch olar

who is concerned with issues that

have been emerging in Nat ive North

American art h istory over th e last

decade,lshe] found Ii sumavut] to be

tremendo usly exc iting and gratifying,

because it demonstrates [0 [herl th at

Inuit art h istory is finally coming

ou t of isola tion and joining in rhe

important dia logu es tha t have

been energ izing other aspects of

Abor igina l 3rt studi es."

H er comme nts were echoed a

year later by Maria von Fincke nstc in,

who wrote (Winter 1997,7) that

"it has bee n a very small field indeed,

dominated by the thinking and

methodo logy of only a few." We can

count on the finge rs of one h and, th e

curators/writers who have had most

influ ence in determining what will

be signified as worthy Inuit art:

Darlene Wigh t and Jea n Blodgett,

both attach ed at one time or another

to The Winnipeg Art Gallery, leap

to the front of the lin e, a reflec tion

on the state of the pla ying fit:ld, not

rhe players.

At thi s time, no Inuit names

can be added to the roster. The Inuit

Art Foundation's Cu ltural Industri es

Training Program- terminated after

12 years because of lack of fundingwas des igned ro help Inuit to ge t at

least a foot in the door (Summe r

20013), but it has had only very

modest success. The grand goal was to

develop "an Inui t cu ltural leadersh ip

tha t [cou ldl influ ence the interpre,

ration of Inuit art and c ulture" but,

given th a t the fundin g was intended

morc [Q support job training than to

boost involvement in the cultural

sector, that lofty goal had to be somewhat played down. Also, we had a

li mited draw, being restric ted to Inu it

living in O ntario and who were

without other resources.

No netheless, we did succeed in

encouraging one student to pursue an

undergraduate degree in art hi story

and sh e has been teaching the under,

grad uate Inuit course at Carl eton

12

I

VOl .21,

NO

4

WINTER

2006

for the last several years (a feat her in

the cap for In uit but also a comment

on the marginalization of Inuit art,

which is, typ ica ll y, ta ugh t by people

without a graduate degree). A few

C ITP graduates did succeed in

enrolling in the C MC's Aboriginal

tra in ing progl(lm and some have found

employment with government and

othe r Inuit organizations. Heather

Campbell wo rked as curato r fo r

INAC before movi ng to Inuit

Tapiriit Kana tami (lTK) an d

Jul y Papatsie co~curated trave ll ing

exh ibitions for INAC and for the

CMC, as well as presenting a paper

at the 10th Inuit Studies Confe rence

(Wi nter 1996046). Pap"Sle also wrote

an art icle about S imon Shai maiyuk

for IAQ, which was published in the

Spring 1997 issue.

In general, Inui t are now playing

more of a role in educati ng the

public about th eir arts. lAF president

Mattiusi Iyaituk has served as a

re$ource person at a Taipe i artists'

symposium (April of 1999) as well as

in Siberia (June of 2002) and other

places. C loser to h ome, h e recen tly

gave a talk at the McCord Museum

in Mo ntreal (Fall 2006043). It is

quite typical for even older generdtion

bilingual Inui t artists-like Ke noj uak

Ashevak (Fall I 997,20)-to attend

exh ibitions of their work abroad ,

and it is not unusual now to find

Inuit speaking out at symposia and

serv ing o n boards of muse ums like

the ROM. Inuit a rc also some times

h ired to teach art to Inui t and

others (for instance, at the Vermont

Carv ing Studio, Arctic College, the

Ottawa School of Art and Labrador

College) . These have been small,

but promising, steps.

The eve r'present dange r is, of

cou rse, tOken ism (the oppos ite of

exclusion on the basis of rigid sta n~

dards). I was not impressed with the

now defunct Canad ian Esk imo A rts

Counci l's latter,d ay efforts {Q include

Inuir.. The process was foreign to Inuit

and the operdting assumption on the

part of the cou nc il appeared to be

that they wou ld ri se to th e occas ion.

In the same vein, things have

changed dramatically since the

1992 symposi um organ ized by th e

McM ichael Canadian Collection,

which angered Inuit part icipants,

who felt they had been upstaged by

non,lnuit. Seve ral we re ou tspoken

abou t the inequality of th eir trcat~

ment. Iyola Kingwatsiak of Cape

Dorset said: "We sat there like pieces

of art in a showcase d isplay ... The

whi te people dom inated as usual.

Th ey thi nk th ey arc the experts

and know eve rythin g abo ut Inu it"

(Sprin g 1992:28).

Western Pra(ti(e the

Starting Point

"It is encou rag ing to note the critical

scrut in y be ing brought to bear on

museum practice and the brave,

if tentati ve, efforts being made to

share power with Inu it producers"

(ed itoria l, Summer 1997:9). But a

major difficulty in trying to achi eve

equality in th e mu seum is that the

starting point has to be western practice. The idea of collect ing, d isplaying

and intcrpreting "art" is fo reign to

Inuit and many othcr n o n ~weste rn

peop le, Whi le Inu it may influence

what material is included in e xhibi~

ti ons and what is said about it, it

is most unl ikely thar they cou ldor would eve n waO( to----depart

appreciably fro m accep ted museum

practice. Th ey are , in fact, setting

up community museums that mimic

weste rn museums-with some nice

innova tions, As much as we want to

pretend o th erwi se, Inuit and ocher

Nat ive people have little choice but

to adopt the frame of reference, if

not the sta ndards already in place.

Understandably, all of the players

start with known practices, al though

the more flexible the institut ion , the

more ope n it will be to unconven~

tiona l ideas as to what to exh ibit

and how.

The inevitable resu lt, at least

ar this early stage, when western

institutions attempt co include non~

western concepts, is confusion and

ambiguity, as was ev ident at the fi rst~

eve r meeti ng of Canad ian Aborigina l

curators in Ottawa in 1997,6 Lee

Ann Mart in (then chi ef curator,

Mackenzie Art Ga llery in Regina)

and Morga n Wood (then cu ra torial

assista nt~ Ctl nadian art at the National

Gallery of Canada) reported on the

conference for us in an article entided

"Shaping the Future of Aboriginal

Curatorial Practice" (Summer

1998:22). Most interesting to me

was that the Native cura tors at the

meeting deplored the tokenism of

hi ring Aborigina ls with "no back;

ground in the arts or c urator ial

motivation." In sp ite of what they

referred to as conflicti ng value

syste ms, they appeared to be cha mpi~

on ing the we ll ~establ i sh ed norms for

curatorial pract ice and were worried

about thei r being degraded (ibid., 23).

The main issue for them, as Native

curators, was to be fully integrated

into the muse um co mmu nity rather

than bei ng trea ted as "cheap labour. "

As it scood the n, they were, they

said, "seldom all owed to tak e respon ~

sibil ity within the insritution or

within the curatorial profession"

(Summer 1998:23-25 ).

The ever-present

danger is, of

course, tokenism,

the opposite of

exclusion on

the basis of rigid

standards

This ambivalence is, I think,

matched by the ir non ~ Native curato~

rial counterparts who also struggle to

reconcil e a desi re to be inclusive with

the need to maintain professional

practice. To quote Li bby Hague's

rev iew of th e McMi chae l's Cape

Dorse t d rawing exh ibit ion, they

"must balance receptivi ty to Inuit

interpretations with the responsib ili ~

ties of scho larship" (Fa ll 1991:11) .

Balandng Needs

A s I wrote in a 2001 ed ito ria l

(S ummer 200 1:3): "The professional

invo lvement of In uit has been the

mi ss ing li nk to a fu ll apprec iation of

th is artform." Researchers have long

re lied on interviews with artists and

some have attempted to involve

them as coll aborators (as opposed to

consultants) on their various projects.

There are many references in IAQ

to the efforts being made to involve

Inui t at all leve l s~ in clud ing the

conceptualizing process-a nd the

shortcomings of these efforts.

In a landmark series of interviews

wi th curators of In uit art published

in 2000, for mer lAQ staff write r

Kate McCarthy specifica lly addressed

the issue of curatorial coll aboration.

By tha t time "collabo ration and

consu ltation with the concerned

commun ities, once rare in the

museum world, [had] become a critical

part of the exhibition development

process, although stili controversial

and ofte n difficu lt w negot iate"

(Spring 2000: 16, editor's note).

In an introductio n to the inter,

view se ries, Doroth y Speak recapped

the Lub icon's 1988 boycott of The

Spirit Sings and the 1989 denounci ng

of Inw rhe Heart of Africa by the fledgling Coalition for the Truth about

Africa, which considered th e RO M

exhibition to be rac isr. "M useu ms

and cura tors are being urged to re'

exa mine their role and fu nction / '

she wrote (ibid., 18). C iting Mary

Tivy (1993), Speak reiterated that.

... to present Indian artifacts as a

substitute for the living pre.)ence

and vision of Native American

people, as if objects and not people

epitomize culture, is a distortion.

To minimize living presence and

live performance as a vehicle

of expression. as museums do

by nature , is to negate a 'way

of knowing' that is recognized

as essential by many Native

American societies.

McCarthy'S in terv iews were

focussed on C MC cu rators since

the CMC was leadi ng the way in

deve loping a model of co ll aboration,

fo llowing its successful engage ment

of Inuit women in the planni ng and

execution of [sumavut, which opened

in 1994. One year later, Judy Hall, cocurator of Threads of tlte Land involved

Pauktuut it, the Inuit women's o rga~

niza tion, from the idea s tage~ giving

them a veto over the very concept

of the exh ib itio n. Once the goahead was received ~ Sall y Webster

of Pauktuutit served as coll aboracor

for the exhibition and representmives

from all the communiti es to be

presented we re invited to serve on

a des ign team. They were brought

to Ottawa to work with the clothes,

rather than merely work ing

from photographs.

Describing herself as a fac ili[3tor,

Hall says she d id th e resea rch and

IN UIT

ART

QUARTERLY

I

13

orga ni zing while Inuit directed the

deSi gn and content (Spring 2000,24).

"The key," she said, was "how did

they want to be represented!" Also,

"we were always asking ... 'How do

you wa nt people to feel about you

when they come out of th is exhibit?

What do you want them to have

learned about you?'" (Spring 2000,24).

gone some distance towards meeting

a wish exp ressed by Ga ry Baikie of

the Torngasok C ultural Centre in

Labrador, who wrote that he would

like co see museums have "Nati ve

people on staff who they can co n ~

sui t with whe n d isplays are bei ng

mounted" (Fall 1993,9) . The First

Peoples H all, a direct response to

Museums "must balance a receptivity to

Inuit interpretations with the responsibilities

of scholarship" - Libby Hague

What difference does it make?

One result of the collaborati on

was the incl us ion of contempo rary

clothing-ski jackets and tee shirtsa direct response to Inuit objections

[Q always being presented as they

lived in the past.

Jea n Blodgett and Susan

Gustavison of the McMichael

Canadian Coll ection also tried to

include artists in unprecedented ways

in their 1999 Northern Rock exhibition. Gustavison , who also descri bed

herself as a facili tator (my "history

bits," she said, "set the stage" and

"put the artists' informati on in co n ~

text"), saw the curator's rol e as one

of balancing needs (Winter 20003),

"There is no set model; there was

no book I could go to that wou ld tell

me that now I'm at step fi ve, and

should soon start step six. It's a much

more organic process. You're always

balancing how to display the art, how

to give the artists a voice and how to

meet the visitors' needs."

It might have been impractica l to

include Inu it arrists per se in conce p~

tua lizing the Narrhem Rock exhibition

and in making decisions about which

artworks would be included, but the

McMichae l tea m took an innovati ve

tack by focuss ing on a topic that

Inui t artists have identified as crucial: the stone. Gustavison told me

that she had read every word ever

pr inted in IAQ about the difficulti es

of getting stone and she and Blodgett

met face to face with man y artists in

their own communities and gave them

ample room in the catalogue in which

to voice thei r views. 111e CMC's First

Peoples Hall- a 21,000 square foot

permanent display tracing Canadian

Aboriginal hiswry-seems to have

14

I

VOL . 21,

NO . 4

WINTER

the 1992 task force orga nized by the

CMA and the AFN, invo lved exten~

sive consultation with Native people

over many yea rs. In an interview

with Kate McCarthy, Bob McGhee

of the CMC ad mi tted that the

museum had been worried about the

costs of the consultation bur, n o n e~

theless, director George McDonald

had been very supportive and the

hall opened in Jan uary 2003

(Summer 2000,19).

And , at the AGO, An Inuit

Pers/Jective: Baker Lake Sculpture,

the first major exhibition organ ized

by Inui t (facilitated by Marie

Bouchard) opened in December 2000

(Spring 200U 4) . Organized by

ltsarnittakarvik: Inuit Heritage Centre

in collaboration with the Art Gallery

of Ontario, it d rew on the Sarick

collection, which had been donated

to the AGO; the art ists were invited

"to decid e for themselves which of

their works from the Sarick collection

shou ld represe nt them in the ex h ib i ~

tion" (ibid., 35).

The Baker Lake ex h ib it ion

was well received, but did n't create

as much of a ripple as Transitions:

Contemporary Indian and Inuit An,

a 1997 exhib ition sponsored by

lNAC and the Department of

Foreign Affairs and International

Trade and co~curated by Anishinaabe

artist/curator Barry Ace and Inuk/

northern cultural research officer

July Papatsie, both em ployees of

lNAC. N oting that curators' voices

often silence those of the artists, th e

Transitions curators made a deliberate

effort to let the artists present their

work, replacing curatorial analysis

with artist commentary. In this ex h i~

bition, the curators' fun ction was

2006

"to assemble the art, not to explain

it" (editorial, Spring 1998,3 ).

Heav ily promoted by the Canad ian

bureaucracy and fo reign embassy

staff, Transitions was, I think, routed

more for its contemporary subj ect

matter than for the fact of its having

been curated by membe rs oftwo of

Canada's indigenous co mmunities.

Transitions was followed by

Transitions II, co~cu rated by Mohawk

Ryan Rice and Labrador Inuk BatT)'

Po ttle, Papatsie's rep lace ment at

INAC. Accordi ng to Pottl e, th is

second effort was an attempt "to infuse

new blood inro th e coll ec ti on by

assembling artwork th at challenges the

stereotypes of First Nations and Inuit

art" (Spring 2001,57). Tramirions 11

was not particularly well rece ived,

and was, in fact, withd rawn from

circulat ion by OlAND, because of

damage to the artwork.

In terms of content, it is interesting

to note that the Native curators of

the two Transitions exhibitions de lib erately departed from "the customary

fare offe red to peop le presumed not

to be knowledgeable about Inui t art"

(see ed itorial, Spring 19983). Even

though these exhib itions were o rga~

nized for international travel, they

included work that would be shocking,

even to domestic audiences. Papatsie

wrote in his essay that the works in

the first Transitions exh ibition contrad icted "the common pe rception

that Inuit art is simply arct ic animals

and scenes from the past" (catalogue

1997:4). And, referring to western

art discourse "as a n eo~co l o nial

dev ice" excluding Indians and ren~

dering their art sta tic and peripheral,

Barry Ace wrote that Nat ive art is

often di smissed as "unauthentic"

when it incorpora tes It noticeable

signs of modernity" (ibid., 8). This

is a se nt imen t all too fami li ar to

Inuit who have cau se to think that

the market craves endless ve rsions

of a romanticized past.

Curating their own ex hibi t ions

is a big step forward from serving as

consu ltants or co-curators with nonNatives. Over the last decade or so,

Inuit have also begun setting up their

own museums and heritage centres

with their own rules. As Gary Baikie

wrote (Fall 1993,9), the people in

Labrador [arel interested in setting up

their own, Inuit, museum in order "to

recover their heritage and present it in

a way that is meaningful fo r their children." Like many, Baikie deplored the

showing of Inu it "out of context. " As

he put it: "You on ly see how we used

to live and not how we live today."

Iqalu it's Nunatta Sun akkutaangit

Museum (NSM) opened its pe rmanent facil ity in 1985. Leah Inutiq,

a local ln uk who did not have any

[f(lini ng in museology, served as

cu rator and manager for one and a

half years before being fired (in 1990)

beca use, she says, "they {muse um

board] didn't feel comfortable with my

presentation of the Inuit viewpoint"

(Inuit An World, Fall/Winter 19901

199 1,90). Specifically, "we had a

stol)' hour with elders te lli ng children

legends and songs, some of wh ich

contain references to private parts,

which English peop le fee l is obscene.

But to us, it's just naturaL" She wondered whether she "should separate

the people and tell one side one

thing and the other side another,"

but concluded "that's not the way to

make it understandable" (ibid., 9 1). 7

That was Leah 's view. Helen

Webster, chair of NSM had a d ifferent

take on the siru3tion: "Leah resigned

because she reali zed the position needs

someone bet te r ab le to manage.

She lac ked th e necessary sk ills."

As she saw it , "Inuit art is presented

in a very sophist ica ted way. Inui t

have not yct progressed [Q that stage.

There is a lot to be done before they

understand what a museum is and

before there arc In ui t who are properly

trained to run a museum" (ibid., 95).

There was to be no inclusion for

the sake of inclusion in Iqaluit.

And Balancing Voites

The curating of exhibi t ions, the

writing of arti cles and the establishment of their "own" museums are

contribution s to an Inu it h istory

of Inuit art , but power relations

inev itably determ ine whose story

and whose art gets attention.

In 2003 (FallA6), 1 reviewed a

valu able coll ection of essays about

cu ratorial po l icy and practice in

Ca nada: O n Aboriginal Representation

in ,he Gallery, edited by Lynda Jessup

with Shanno n Bagg. "More reflective

than defin itive," this collection

of essays flowed out of a wo rkshop

dev ised "to address the ongoing

limitations to full representation of

Native visual culture in the pub lic

art ga llery." Jessup's own contr ibut ion, entitled "Hard Inclusion," makes

the point that "in spi te of ~ ll that has

been sa id and promised, Native North

American arts remain marginalized in

public art gal leri es," although they are

"increasingly visible in anthropological museums, cultural centres and

comme rcial galle ries."

In the same book, Mohawk curator

Lee A nn Martin suggests that public

ga lleries th ink they are be ing let off

the hook because their policies do

not specifically exclude Abo ri ginals

and because they do, from time to

time, include Aborig in al art in the ir

ex h ibition programs. Martin refers to

th is as "soft" inclusion or "tokenism."

"As a field, Inuit art has been and

continues to be overwhelmingly dominated

by non-Inuit specialists talking and writing

about Inuit people" - Norman Vorano

The ball could be seen to be in the

court of the Native people. In sp ite

of an unequal playing field, nonwestern artist.s, specifi ca lly Ca nadi an

Inui t, may succeed in finding a way

to open the door for th emselves and

their art. Wh ile Inuit art is pretty

well identi fied with stone carving

and, to a lesser extent, prims, the

key may prove to be the camera,

which some Inuit have embraced

with gusto. Perhaps because of its link

with oral tradition- it can be viewed

as an extension of the oral trad itionthe came ra has permitted Inuit to

insert themselves into the contemporary mainstream art world in a way

tha t stone sculptors have not. As

Norman Varano says (persona l commu nication) , "It is not su rpr ising

that individuals from an oral culture

have nO[ made many inroads into art

history, a re lenrless ly li terary-based,

Eurocentric d iscipline, rooted in

ncnde mic institutions and programs

that the North lack ," whereas

"film mak ing seems to be perfectly

suited fo r Inuit as a way to engage

with h istory, social issues, gender,

colon ialis m, and m her top iCS that are

ra rely broached in th e comm ercial

world of In ui t art. "

INUIT

A RT

QUARTERLY

1

15

While we str ive to incorporate

diversity- in the museum and else·

where-th e Big Q uestion remains

as to wh ether or not all paths lead

but to assimi la tion. Probabl y. But

what is be ing ass im ilated to--as well

as what is be ing ass imilated- is in a

constant state of fl ux, which mak es

the outcome unce rtain and the game

worth playing.......

is pursuing a Ph D in 3rt hi story at

Carl eton University in O ttawa.

It must be said that the CMC has

had a checkered history. In 1991 ,

it was criticized in IAQ for showing

Masrers of the Arctic, a regress ive

exhi bition organi zed by A mway

Corporati on. In her review,

Dorothy Spea k (Spring 1991 :39)

said: "The exh ibition is alarming

beca use it appro(lc hes In uit art ists

and their work not as individuals

but as an ethn ic group produc ing

a homogeneous 3rt with one mes·

sage. Th is is exactly [he image of

Inu it art and arti sts aga inst which

collectors, scholars, curators and

institutions have been fighting

for 40 yea rs." The C MC was also

cri tic ized, in IAQ and elsewhere ,

for its treatment of Inu it- the

peop le not the 3rt-at the opening

of Iqqaipaa, a 1999 ex hibition to

honour the bi rth of N unavu[.

Artists represented in the exhibi·

tion were not invited to a VIP

reception although "in a tip of

the hat to mul ticulturalism, Inu it

provided musica l entertainment"

(Fall 1999J). A few days later, the

museum hosted Nunavut Day, but

Inuit watched th e proceed ings on

a TV in the basement, excluded

from the theatre, which was by

invitation only. Perhaps all this

proves is that progress is not linear.

NOTES

During the tenu re of Kathleen

Fcnwick-cu rator of prints and

drawings from 1928 to 1968, and

also a member of the Canadian

Eskimo Ar ts Co un cil- the

Nati o nal G a ll ery of Canada

had been one of the first public

insti tutions to show Inuit prints

and sculpture. After Fen wick's

retirement, th e gallery ceased

coll ecting and exh ibiting Inuit

art (von Finckensrc in, Winter

199M- 7) .

"Filmmaking seems

to be perfectly

suited for Inuit as a

way to engage

with history, social

issues, gender,

colonialism, and

other topics that

are rarely

broached in the

commercial world

of Inuit art" -

2

Setting as ide considerations of

policy, there has been at least

an effo rt to provide train ing in

museology to Native peoples. At

a 1989 meet ing to discuss the

transferring of the INAC coll ec·

tion, the representative from the

Government of the Northwest

Terr itori es proposed that the co l·

lecti on be transferred to the In uit

C uiturall nstitute-based in the

NWT-and she also asked for

money to establish museums in the

North and to prov ide training in

museolob'Y for Inuit. The response

from a representative of the now·

defunct federal Department of

Co mmunicat ions was that the

trai ning of Nati ve people in muse·

o logy had been made a priority

(Win ter 1989:33). Canadian

Heritage (wh ich replaced the

Department of Communications

in 1996) currentl y has no prog ram

to ass ist in the tra in ing of N at ive

peopl e in museology.

Norman Varano

4

16

I

V Ol.21

N O

4

WIN TE R

Hsio.Yen Shih's appellation is

ironic , given that Inui t them·

sel ves now refer to some of the

hastier, less inspired work they

produce as "bingo art," by wh ich

they mean work produced to earn

some quick cash with which to pl ay

bingo, a popular arctic pastime.

20 06

It is promi sing to note that, at

time of writ ing, at least one In uk

6

July Papatsie, th en work ing at

Ol AND, was the o nl y In uk at

this conference.

There 3re three ethnic groups in

Iqaluit: Inuit represe nt 50 per

cent of the popul at ion and the

remainder are French and English.

REFERENCES

Ace, Barry and July Papatsie

1997 Transitions (exhibit ion cata·

logue). Ottawa: Indian Affairs

and Northern Affairs Ca nada with

the Department of Foreign A ffairs

and International Trade

Pottle, Barry and Ryan Rice

200 1 Transitions If. (exhibi t ion

catalogue). Ottawa: Ind ian and

Northern Affairs Canada

Freeman, Minnie Aoudla, Odette

Leroux and Marion Jackson, eds.

1994 Inuit Women Artists. Ga tineau:

Ca nadian Museum of C ivili zation.

FEATURE

18

I

VOL . 21 ,

NO . 4

WINTER

2006

INUIT

ART

QUARTERLY

I

19

Owls, distortions, dream states,

and the implied reference to cubism

and surrealism became consistent

features in Massie's work over the

next n ine years.

While the theme of family would

be consistent over the years, Massie's

material for carving would change

from Labrador stone to stone from

a quarry near his current home and

studio in Kippens, Newfoundland.

"I try to evoke the playful

side of things in most of

my work," says Massie

Another work, grandfather 1 have

something to tell you (2005; below) is

a childhood confession in anhydrite,

a local limestone. Admonished never

to kill an animal that would not be

eaten, Massie, aged 12, disobeyed

and shm a tom-tit with his pellet

gun. In a flurry of guilt, he buried

the tiny bird with a kitchen

spoon and never told his grandfather or parents about it until

making this piece 30 years later.

The face of the stone carving

is awash with emotion: twisted

mouth agape, nostrils flared, eyes

wide. The figure is on bended

knee in supplication, but the

limp body of the bird is still concealed behind his back. Capturing

the delicate moment when the

figure approaches his grandfather

but hasn't yet presented the bird,

the viewer is in a privileged position.

A close-up of the bird's face reveals

Xs marking its lifeless eyes, contemporary graphic language from the

world of cartooning integrated within

Inui t stone carving.

The other self-portrai t in the

exhibit ion, he gathers limestone to

carve- portrait of ,he artist (2004),

is carved from- as the title suggests-limestone. In this piece, the

figure is surprisingly simple and

straightforward, its only extraordinary feature being a protruding

tongue, suggesting the exertion of

gathering stone. The artist was

clearly enamored with the komatik

(sled), however, as its every aspect

is marked by a faithful attention to

20

I

VOl.21

NO . 4

WINTER

2006

Michael Massie in his studio with his teapot

rep-fea-lio. LAd Lr'. - P"'''"\ CTt><""c... ..

detail. The use of real chunks of raw

quarry stone, and the intricate sinew

lashing that secures them to the

komatik suggest that great care was

put into crafting rhis work. For the

contemporary artist who drives a

van and uses power tools in his art

praC[ice, the sled was Massie's salute

to "the old ways of doing things."

The importance of family connects

Massie's stone carving and silver

work. Even in the simplest of pieces,

such as his ulu bowls, the central

theme is family. An ulu, or woman's

skinning knife, is a customary utensil

used to prepare or divide meat. In

Massie's ulu bowls, the bowl, which

represents the kudlik (a soapstone

vessel used in the burning of oil for

heating, cooking, or celebration), is

(detail] grandfather I have something

to fell you, 2004, Michael Massie.

(for left) grandfather I have something to fell you, 2004 (anhydrite,

bone, bird's eye maple, mahogany

and ebony; 17.25 x 9.25 x 12 em;

collection of The Rooms Provincial

Art Gallery). Lll.d Lr'. - P"'''"\

CTI><.. c... ..

blind man's vision, 2003, (limestone, tagua nut, ebony and bone; 21.59 x 28.58 x 21.59 em;

private collection). Lt:.d Lr', - PK\ crt><:<O-L

supported by three ulu~shaped forms.

Massie explains: "The three ulus,

to me, represent a family. Each one

helps the other to survive. That is

why they are forming a circle. I like

using the ulu and kudl ik together;

th e feeling of them supporting each

other and becoming one unit."

As a forum for shari ng knowledge

between generations, and sharing

experiences through daily rituals,

the family is a sou rce of comfort,

instruction, and respect for Massie.

Like the three ulus, he also Interprets

the pieces of a tea set as members

of a fam il y. Massie envisioned his

ancestors regrouping in together for

tea, tea set #i (199 7) and represented

their sp iri ts in the eyes on the finials

of the teapot, creamer, and sugar

spoon in the bowl. By contrast,

little Jimmy, 'ea set #iv (2000) is

non~narrative or pure design work,

with an energetic combi na t ion of

moving angles extended into space

by dynamic wood handles. Still, it

is named for James Baibe, Massie's

maternal grandfather, who passed

away while he was working on the

tea set.

In festivi,ea rea set #v (2005),

the tea set as family gets its most

literal representation. The teapot has

become a father brandish ing a fishing

spear; the creamer is a mother ges~

turing with an ulu, and the suga r is

a little boy with his harpoon. The

<0-

figures have sterling silver bodies

with blood wood arms, bone faces

and horsehair locks. Massie admits

to blood wood being a pun on blood

relatives. As he elaborates, the tray

for the set also has a role to play in

the story:

The tray wa.s made into a circle

to represent the igloo. The struc~

ture of the igloo is low, showing

that spring is upon them, and it

is almost melted. 1 made the tray

smaller than with previous sets, as

I wanted that feding of crowdedness and being cramped-the way

it is with most igloos. The feet

were /Jwbably the most difficult to

design ... The)' are 50 important

to the overall design and 1 went

through quite a number of ideas

before the simplest one was so

obviously the best . Using the fish

INUIT

ART

QUARTERLY

I

21

Wh ile Massie was busy working

out all th e poss ibilities of the ulu

form , h e was also th ink ing about

ways to vary the surface of hi s silve r

te<Jpots. As its name suggests, gray lea

was treated with liver of sulphur to

Form and Etching, from

tone down its reflec tive properties.

Decoration to Narration

As an artist, Massie saw th e silver

The crescent shape of the ulu

surface not as an indication of

has inspired the design of Mi ch ael

preciousness, polite manners, or

Massie's silver work for at least the

valu e, but as frustra ting camouflage.

past 10 years. It h elped to establish

lnterested chi efl y in form , he noted

his recogniw ble style of geometri c

th at the shin y teapots would take on

shapes, elegant lines, and a caneem,

th eiT surro und ings and negate the iT

pOTary character for Inuit art, Both

silhouettes. Eventually, Massie would

boa-tea (1996) and gra y tea ( 1996)

e tch the surface of hi s teapots, but

arc based on ulu fo rms, although

his fi rst attempts were understand·

they are strik ingl y different. The

ably cautious. His first ste rling silv er

boa~tea is essenti ally a semi ~c ircle

Nc hed pots were barel y bitte n by the

poised on da inty feet with a sturdy,

acid bath. Th e surface of $ubdc·tea

curving, tulipwood handle. in contrast

(1997) is sh . ded with delic.te lines

to the symmetry of boa.~ tea, gray tea is

that help define its arching form.

irregul ar, squat, a nd has a vertical,

The technique of acid etching

ca rved walrus tu sk h andle. The ulu

gave Mass ie a way to draw on the

shape is discernible from above , but

surface of hi s fo rms and record infor·

from the rear it is a cubist's adept

ma tion. Bay Sr. George (1997) and

collisi on of angles. From the side,

Gjoa Haven , JqaJuit NWT ([997)

the squat silver form sits on ivory

are ulu bow ls in scribed with maps

feet th at, accordi ng to Massie, take

of diffe ren t places he h as called

th eir insp iration from Marvin the

"h ome." With hi s growing confi ·

Marti an , a cartoon character from

de nce in etching, the interp lay

Bugs Bunn y. "Whenever Marvin got

of surface and form took on new

za pped all you could see was his fee t

possibilities, as can be seen in sal,tea

poking out fro m und er his h elmetwalers (1997) where the vesse l of

that's the Martia n look 1 wanted."

the teapot attain s a nautical quality

It is typical of Massie to comb ine

while the surface depicts seals hUll ting

eleme nts from all th e corne rs of his

fi sh. Th e inve rted heads of seals

world: the welcoming pot of tea ,

wa tching the fish below the wate r

viv id imagery from popular c ulture,

is especially charming.

the ulu knife fro m th e

In the late 1990s, Massie experi.

Inuit lifestyle of his grand·

mented with etching Inuktitut syllabic

parents, and art history

symbols onto his works, as in seed~tea

and design influences fr om

(1998). Dur ing th is time, his work

art school and books.

al so began to embrace more sober

topics. His ode La C harlie (1 998)

refe rs to a fr iend and teacher lost

to suicide; its mu sk ox handl e was

a gift from C harlie Kogv ik. Later,

Massie wou ld return to more tradi ·

tiona I, decorated

forms, including

8th century A D (1 998).

rails for the feet illustrates the

whole purpose of what the family

is doing, and how im/JOrranl the

fish are to their diee.

22

I

VOl . 21 ,

NO . 4

WINTER

Movement

Inspired by th e "pure poetry" of the

ulu, with its graceful a nd rhythmic

rock ing motion, Massie looked for

ways to bring his man y ulu·shaped

teapots to life. Teapots arc comb ina·

tions of positive and negat ive shapes.

Spaces between handle and lid

become charged . The curve of the

h andle ca n dance with the gracefu l

lilt of a spout. O r th ey can take on

the syncopated rhythms of jazz, as in

the sharp a ngl es of AU925. Feet or

legs are also importa nt features of the

teapots. Massie learned earl y on that

a good pot "looked as if it could wa lk

off the tab le top."

Some of Massie's tcapots do, in

fact, rock, such as wesleri)' winds

(1998), a masterful teapot with

streaming handles swept behind its

body. The point of contact between

the curved base of pot and the tab le

surface is so minimal that the slightest

motion wi II cause the pot to rock like

a boat in the waves. Interestingly, the

body of the pot is almost iden tical

in shape to ode to C harlie, sh owing

how Mass ie could create or al te r