Document 10523053

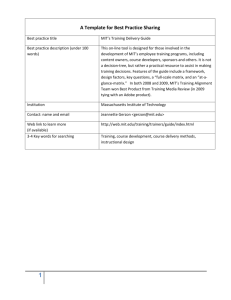

advertisement