Document 10523035

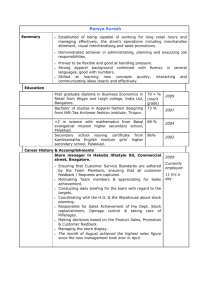

advertisement