SITE PLAN REVIEW IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS:

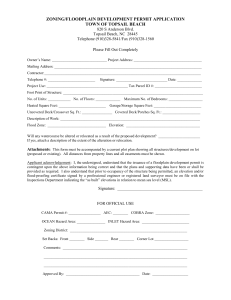

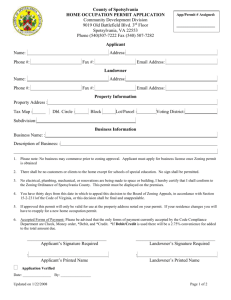

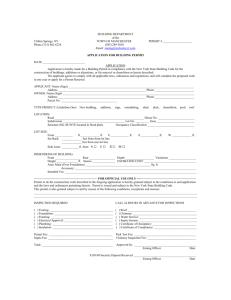

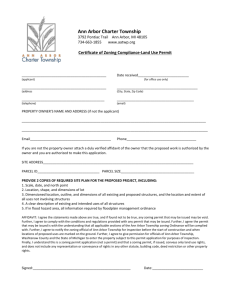

advertisement