Identity Maintenance and Adaptation: a Multilevel Analysis

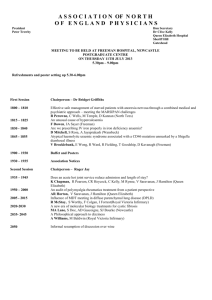

advertisement