354, 2008 The Howard Journal of Communications, 19:334 # ISSN: 1064-6175 print/1096-4649 online

advertisement

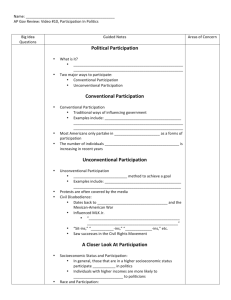

The Howard Journal of Communications, 19:334354, 2008 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1064-6175 print/1096-4649 online DOI: 10.1080/10646170802391755 Assessing Cultural and Contextual Components of Social Capital: Is Civic Engagement in Peril? LINDSAY H. HOFFMAN Department of Communication, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, USA OSEI APPIAH School of Communication, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA Much research on political participation and civic engagement centers on the question: ‘‘What motivates people to get involved?’’ Several communication variables have been purported to influence these activities, such as television, newspaper, and Internet use. The general conclusion is that civic and political participation is declining. However, the rates of decline (or increase) in these activities among certain racial and cultural groups, such as Blacks compared with Whites, is not clear. Furthermore, the roles of religion and the church—an important component in creating bonds and networks that encourage such participation—have received little attention among communication scholars. The authors sought to examine the intricacies among race, religiosity, and political and civic engagement by expanding the current literature on social capital to include cultural and contextual components of church involvement. They found that in a national sample, the more involved Blacks are with church and the more frequently they attend services, the more involved they are in their communities. Moreover, their findings are consistent with previous research regarding media use; newspaper reading, and Internet use were positively related with civic engagement and voting, whereas television use was not. Implications for communication research, social capital, and measurement of race and culture are discussed. KEYTERMS church, community, culture, ethnicity, media use, participation, race, social capital Address correspondence to Dr. Osei Appiah, School of Communication, 3140 Derby Hall, 154 N. Oval Mall, Columbus, OH 43210. E-mail: appiah.2@osu.edu 334 Race and Social Capital 335 Some researchers contend that race does not play a role in influencing an individual’s political participation or civic engagement (e.g., Leighley & Vedlitz, 1999) whereas others argue that race does correlate with these activities (e.g., Abrahmson & Claggett, 1984; Musick, Wilson, & Bynum, 2000). What is certain is that over the last few decades, voter registration, voter turnout, and civic engagement have dropped significantly among Americans (Cavanagh, 1991; Gilliam & Kaufman, 1998; Putnam, 2000). Disparities in political participation by race are not as certain. Many scholars believe that the decrease in voter participation may be greater than average for Black Americans (e.g., Musick et al., 2000). However, there appears to be solid evidence that the political participation gap between Whites and Blacks may be shrinking or may even be non-existent (Abrahmson & Claggett, 1984; Cohen, Cotter, & Couter, 1983; Southwell & Pirch, 2003). In fact, much of the data suggesting Blacks are less politically active compared with Whites seem to result more from differences in socioeconomic status than differences in race (Leighley & Vedlitz, 1999). For example, Barnes’s (2003) study of poor urban neighborhoods found that Blacks were more involved in their neighborhoods than Whites, even after controlling for the constraints of income, transportation, and length of residence in the neighborhood. Communication researchers have become more involved in this discussion of political participation, adding variables like media use, interpersonal discussion, and social networks (Nisbet, Moy, & Scheufele, 2003; Scheufele, Nisbet, & Brossard, 2003; Scheufele & Nisbet, 2003; Scheufele & Shah, 2000; Shah, McLeod, & Yoon, 2001). Rarely, however, do these researchers take race into account. Nisbet et al. did measure religion and race, but focused their attention on belief systems (i.e., doctrinal conservatism) primarily among White Protestants, and grouped non-Whites into an ‘‘other’’ category. It is our contention that the Black religious experience is a unique cultural component and deserves attention within the ongoing discussion of social capital. This study attempts to rectify the problem by drawing attention to the important cultural and structural elements that could potentially influence Black political participation and civic engagement. But first, a general explication of social capital is required. BUILDING SOCIAL CAPITAL Much of the research on political and civic engagement can be classified under the rubric of ‘‘social capital.’’ This concept has been measured in various ways, but it can be defined generally as a multilevel concept that manifests itself in communities through public and private processes and organizations as well as interpersonal communication networks (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Putnam claimed (2000) that the term social 336 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah capital itself has been reinvented at least six times over the 20th century. What these different interpretations offer are an understanding of what Putnam termed the ‘‘private’’ and ‘‘public faces’’ of social capital: respectively, the individual contact that people have with each other and those wider connections within a community that may not involve direct contact. Both concepts are integral to social capital: ‘‘A well-connected individual in a poorly connected society is not as productive as a well-connected individual in a well-connected society’’ (Putnam, 2000, p. 20). For the purposes of the present study, we have chosen to use Silverman’s (2001) succinct definition of social capital: ‘‘a bond of mutual trust emerging from shared values that are embedded in parochial networks’’ (p. 244). This definition reflects the important aspect of shared values and, importantly, places them within local networks. This contextual framework is based in Coleman’s (1988) conceptualization of the term as embedded within a social context. Some of the recent literature overlooks this fundamental contextual element of social capital, choosing instead to focus on individual characteristics (e.g., Brehm & Rhan, 1997; Green & Brock, 1998; Scheufele & Shah, 2000; Shah, 1998; Uslaner, 1998). The importance of examining context, as emphasized by Coleman (1988) is echoed in other scholars’ work, including those in communication (e.g., Ball-Rokeach, Kim, & Matei, 2001). Shah et al. (2001) expanded Silverman’s (2000) definition by incorporating the important element of communication into the concept of social capital. Although mass communication has been labeled the culprit of declining social capital in some circumstances (Putnam, 1995, 2000), studies have shown an indirect positive link between media use and civic participation (McLeod, Scheufele, & Moy, 1999). Tightly knit communities, McLeod et al. argued, discuss and deliberate about topics encountered in the media, which in turn fosters civic participation. Wood and Judikis (2002) echoed this sentiment by stating that in order to maintain solidarity and promote necessary social change, communication needs to occur on a regular basis within communities to remain strong. Moreover, an important component of social capital is that it is more likely to be created in closed, rather than open, networks (Coleman, 1988). Closed networks create trustworthiness—the ‘‘glue’’ of social capital. Moreover, resources play an important role in building social capital (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). Verba et al. found that the lack of resources was a major cause for inactivity in politics. Civic skills were one of the most important resources, and these skills were enhanced through the major institutions with which citizens were involved—including churches. The difference in resources among Blacks and Whites has been documented in studies from a variety of disciplines, such as adolescent psychology (Hirsch, Mickus, & Boerger 2002), urban sociology (Barnes, 2003), anthropology (Shimkin, Shimkin, & Frate, 1978), aging studies (Johnson, Race and Social Capital 337 1995), and Black studies (Bridges, 2001; Pinn, 2002). What is maintained across the literature, though, is the overwhelming influence of the Black church, spirituality, religiosity, and a common cultural history on Blacks’ feelings of connectedness with community. In addition to studies of interpersonal communication and social capital, a fruitful area of communication research has proliferated to assess the relationship between media use and social capital. Media use has been shown to be an important variable in predicting citizens’ civic and political participation. For example, Putnam (1995) maintained that the decline in social capital within the past few decades is associated with the rapid growth in time spent viewing television. He argued that television viewing displaces time that could be better spent working with others on civic or political activities. This ‘‘time displacement hypothesis’’ has sparked an ongoing debate about whether the mass media truly contribute to the overall decline (or increase) in civic and political participation (see Kanervo, Zhang, & Sawyer, 2005; Putnam, 1995, 2000; Schudson, 1999). Given this debate, this study controlled for the role mass media use play in predicting Black and White church-goers’ civic and political participation. POLITICAL MOBILIZATION WITHIN THE BLACK CHURCH Putnam (2000) claimed that churches, or ‘‘faith communities,’’ are the ‘‘single most important repository of social capital in America’’ (p. 66). Yet political communication scholars have not fully addressed the role of the Black church vis- a-vis the White church as a catalyst and mobilizing force for political and community involvement. Religious involvement for many Blacks reflects spiritual, economic, social, cultural, and political dimensions (Barnes, 2003). As the centers of community and religious life, Black churches have historically been the primary sponsors of political leadership (CalhounBrown, 1996; Chaves & Higgins, 1992; Putnam, 2000). Black churches across denominations have a long history and commitment to political issues such as voter registration and the movement of clergy into political office, most notably during the civil rights movement (Pinn, 2002). Indeed, Black churches ‘‘are an important organizational resource for disseminating information about elections, encouraging church members to get involved in politics, providing a space for them to talk about politics, and exposing them to local and national leaders’’ (Harris, 1999, p. 115). Brown and Wolford (1994) referred to this as church-based political action, and argued that this type of Black religious culture encourages members to become politically active. Black congregations also provide churchgoers with communication networks that can be used to coordinate social and political activities within Black communities (Harris, 1999). The organizational skills learned from 338 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah church participation—along with the political communication found therein—are particularly prevalent in the Black church and may promote Blacks’ involvement in politics to a greater extent than White churchgoers. Harris (1999) maintained that Blacks learn a great deal about politics through religious networks and are motivated to participate in political affairs from political stimuli received in church. In fact, studies demonstrate Blacks’ exposure to political stimuli in church increases their political involvement (see Brown & Wolford, 1994; Tate & Brown, 1991). Moreover, through participation in church activities such as choirs, deacon boards, worship teams, missionary societies, user boards, pastor’s aide clubs, and teaching Sunday school, many Blacks acquire the necessary organizational skills to effectively participate in secular politics through the Black church (Calhoun-Brown, 1985; Federico & Luks, 2005; Harris, 1999; Putnam, 2000; Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). In Black congregations, a genuine commitment to politics is often reflected from the pulpit. In Black churches, ministers often include political material in their sermons, give political groups access to their congregations, and mention opportunities to campaign for political candidates (Greenberg, 2000). The involvement of Black clergy in politics coupled with the strong emphasis placed on political discussion in the Black church has led several researchers to conclude that the Black church has played a critical role in mobilizing Black political participation (e.g., Calhoun-Brown, 1996; Leighley & Vedlitz, 1999). The Black church’s ability to politically mobilize their congregation is even more remarkable when compared with political mobilization by White mainstream churches. According to a Northwestern University survey (cited in Harris, 1999), Blacks were nearly three times more likely than Whites to state that their religious leaders discussed politics during religious services nearly all the time. Blacks were also twice as likely as Whites to hear frequent discussions of politics from their clergy and to be encouraged to vote (Harris, 1999). Whereas White churches often stop short of urging members to vote for particular candidates (Greenberg, 2000), ministers in the Black church frequently allow political candidates from both sides to speak to the congregation during church services, and strongly encourage political and civic engagement among the members (Greenberg, 2000). Moreover, clergy discussion of political matters has been found to be relatively infrequent in White churches, when compared with Black churches, and such discussions appeared not to stimulate political participation (Harris, 1999). This is evidenced by research that demonstrates Black churches are more than twice as likely as Whites to receive visits from political candidates and to have had money collected for a candidate during church service (Harris, 1999). Therefore, it appears that Blacks may receive more political communication stimuli at their place of worship than Whites, and, as a result, the Black church has led several researchers to conclude that the Black church has Race and Social Capital 339 played a critical role in mobilizing Black political participation (e.g., Calhoun-Brown, 1996; Leighley & Vedlitz, 1999). However, much of this participation could vary depending upon Black individuals’ church attendance and involvement. CHURCH ATTENDANCE AND POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT Several studies have found a positive link between church attendance and voter turnout (Brown & Brown, 2003; Macaluso & Wanat, 1979, Martinson & Wilkening, 1987; Strate et al., 1989). Research has shown that regular church attendance among Blacks promotes political involvement, increases awareness of policy issues, and instills in its congregation a sense of civic obligation that increases willingness to participate in elections (Brown & Brown, 2003; Harris, 1999). Church attendance also helps develop a sense of civic duty, and exposes Black church members to political information that is likely to lead them to vote (Harris, 1999). In support, Taylor and Thornton (1993) found that church attendance was positively related to both presidential, state, and local voting among Blacks. Attending church services and participating in other church activities that develop civic skills, such as retreats, choir, or serving on church committees enhances individuals’ civic skills, civic duty, and motivates them to become politically active (Brown, McKenzie, & Taylor, 2003). It is important to determine the extent to which both church attendance and church involvement are significant predictors of Blacks’ political involvement and civic participation. This is important in light of evidence that suggests church attendance may be a weaker predictor of Blacks’ political behavior. For example, in their examination of both the 1980 National Survey on Black Americans and the 1994 National Black Politics Study, Brown and colleagues (2004) discovered that, although church attendance was positively associated with certain political behavior, church involvement was shown to be a stronger and more consistent predictor of Blacks’ political activism. Brown et al. (2003) argued that simply attending church is not a consistent predictor of voting or other political behavior, and may not provide sufficient social and political activities to adequately move Blacks to vote or engage in civic work. Therefore, church participation may be a more reliable predictor of a range of political behavior among Black church-goers. Recent research, however, has suggested a decline in religious participation (Putnam, 2000). Putnam acknowledged, though, that this decline has not affected the fraction of the population that is intensely involved in church life. Moreover, there is a marked difference among denominations; Protestant and Jewish congregations have lost membership, whereas other denominations (such as Southern Baptist) have grown. There appears to be a difference, then, in attendance among denominations characterized 340 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah by different cultural compositions. In fact, Taylor et al. (1996) found that Blacks exhibited higher levels of religious participation than Whites regardless of socioeconomic status, region, and religious affiliation. These authors concluded, ‘‘Given the prominence of the church, it is conceivable that race differences in religious involvement are partially explained by the integral and comprehensive functions that religious institutions perform in Black communities’’ (p. 409). Given the emphasis Black churches and ministers place on politics and the amount of political communication that occurs in Black churches, it is reasonable to expect that Black churchgoers will be more politically active than White churchgoers. This leads to the first set of hypotheses: H1: Blacks with high levels of church attendance will be more likely to have voted in a national election than will Whites with either high or low levels of church attendance. H2: Blacks with high levels of church involvement will be more likely to have voted in a national election than will Whites with either high or low levels of church involvement. THE BLACK CHURCH AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT Civic engagement is an essential component of social capital—and the one that many scholars fear is declining across the United States (e.g., Putnam, 2000). Such community outreach, however, is often stressed by religious institutions, particularly the Black church (Greenberg, 2000; Pinn, 2002). Black churches are also more engaged in civic activities than White churches (Chaves & Higgins, 1992, Harris, 1999; Pinn, 2002). Other researchers argue that Black churches, overall, are more socially active in their communities than White churches and that they also tend to participate in a greater range of community programs (Chaves & Higgins, 1992). According to Pattillo-McCoy (1998), ‘‘the black church is the anchoring institution in the African American community’’ and ‘‘is often the center of activity in the black communities’’ (p. 769). In addition to being more involved in the community, Black congregations are significantly more likely to participate in community programs that benefit the needy and disadvantaged than White congregations (Chaves & Higgins, 1992; McCarthy & Castelli, 1998). The Black church’s commitment to the community has centered on problem areas such as housing, welfare, police and community relations, and local community events (Greenberg, 2000; Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). In addition, Black ministers typically preach that civic duty is part of the obligation of being a Christian and stress the importance of Christian voices being heard in the community (Greenberg, 2000). In addition to being Race and Social Capital 341 exposed to this call to civic duty, Black churchgoers could have a deepseated interest in participating in their communities. Historical connectedness, or a sense of a ‘‘linked fate’’ (Federico & Luks, 2005, p. 662), as well as residential segregation, economic problems, and discrimination encourage civic involvement ‘‘as a response to spatial compression and the inability to travel outside local boundaries’’ (Barnes, 2003, p. 465). This genuine interest in the community may explain why Blacks rate their communities—even communities where they are the numeric minority—more favorably than Whites rate their own communities (Krysan, 2002). Studies on urban neighboring show that Blacks establish friendships and connections to voluntary organizations in their neighborhoods more often than Whites (Oliver, 1998). Moreover, Blacks vis-a-vis Whites are also more likely to know their neighbors, and be involved in religious, political, and social groups in their neighborhoods (Oliver, 1998). Although churchgoing Blacks tend to participate more in their communities than Whites (Barnes, 2003), it should be noted that Blacks who are less religious and less involved in the church are less likely to get involved in community activities compared with more religious and church-going Blacks (Sherkat & Ellison, 1991; Pattillo-McCoy, 1998). Given that Blacks tend to find their communities more desirable—combined with the emphasis of the church to work in the communities—churchgoing Blacks are perhaps more likely than Whites to engage in community activities. This leads to the next set of hypotheses: H3: Blacks with high levels of church attendance will demonstrate more civic engagement than will Whites with either high or low levels of church attendance. H4: Blacks with high levels of church involvement will demonstrate more civic engagement than will Whites with either high or low levels of church involvement. METHOD Sample Data for this study were obtained from a research study undertaken by the Saguaro Center at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. This ‘‘Social Capital Benchmark Study’’ was conducted nationally as well as in 41 communities. The purpose of the survey was to provide a large dataset on social capital to academics, and to provide communities with tools to assess their levels of social capital and measure progress (Social Capital Community Benchmark Survey, 2001). The survey was conducted by telephone using random digit dialing (RDD) during the period from July to November, 2000.1 Response rates averaged 28.9% for the community samples and 28.7% for the national sample, using the AAPOR RR2 formula 342 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah (Saguaro Seminar, 2001). Interviews averaged 26 minutes in length. The majority of the local community survey used proportionate sampling and samples ranged from 500 to 1,500 interviews (N ¼ 26,230).2 The national sample oversampled Blacks so we were able to include 2,942 Blacks in the present analyses and 17,115 Whites. This was one of the major advantages of this data set, as it is often difficult to obtain such a large number of Black respondents in a national sample. Measurement INDEPENDENT VARIABLES The primary independent variable in this study was race. Only Blacks and Whites were examined in the analyses, with Whites coded as ‘‘0’’ and Blacks coded as ‘‘1.’’ We also included both church attendance and church involvement. Attendance was measured by asking a single item: ‘‘Not including weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services?’’ Responses were less than a few times a year, a few times a year, once or twice a month, almost every week, or every week or more often. Church involvement was measured by a single item: ‘‘In the past 12 months, have you taken part in any sort of activity with people at your church or place of worship other than attending services? This might include teaching Sunday school, serving on a committee attending choir rehearsal, retreat, or other things.’’ Answers were coded dichotomously as either yes or no, so scores range from 0 to 1. Demographic variables were also included as controls in our regression analyses. Education was measured as a trichotomous variable, as high school or less, some college, or college degree(s). Total household income was measured on a scale of 0 to 7 in ordinal categories that represented $20,000 or less to $100,000 or more. Media use was analyzed based on respondents’ television, newspaper, and Internet use. Television use was measured by asking respondents how many hours per day they spend watching television on an average weekday. Newspaper use was measured by asking respondents how many days in the past week they read a daily newspaper. Internet use was measured by asking respondents how many hours did they spend using the Internet in a typical week. Similar to previous studies, the media use variables are entered into the model after controlling for the effects of demographic variables (see Kanervo et al., 2005 for a review). The demographic variables were education and total household income. DEPENDENT VARIABLES Voting was measured by a single item, which asked whether respondents voted in the presidential election in 1996 when Bill Clinton ran against Race and Social Capital 343 Bob Dole and Ross Perot. Answers were coded ‘‘1’’ if respondents voted and ‘‘0’’ if they did not. Civic engagement combined 15 variables that measured participation in a variety of community activities in the past 12 months: an adult sports club or league, or an outdoor activity club; a youth organization like youth sports leagues, the scouts, 4-H clubs, and Boys & Girls Clubs; a parents’ association, like the PTA or PTO, or other school support or service groups; a veterans’ group; a neighborhood association, like a block association, a homeowner or tenant association, or a crime watch group; clubs or organizations for senior citizens or older people; a charity or social welfare organization that provides services in such fields as health or service to the needy; a labor union; a professional, trade, farm, or business association; service clubs or fraternal organizations such as the Lions or Kiwanis or a local women’s club or a college fraternity or sorority; ethnic, nationality, or civil rights organizations, such as the National Organization for Women, The Mexican American Legal Defense, or the NAACP; other public interest groups, political action groups, political clubs, or party committees; any other hobby, investment, or garden clubs or societies; and other. This was also a yes=no response item with a range from 0 to 15 (Cronbach’s a ¼ .701). RESULTS A series of regression analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses. Education and total household income were included in the first block. Although not central to this study’s hypotheses, three types of media use—newspaper, Internet, and television use—were added in the second block as control variables. The race and religious variables were added in the final block. The first two hypotheses predicted that voting in a presidential election would be predicted by the interaction between race and church attendance or involvement. Hypothesis 1 proposed that Blacks with high levels of church attendance would be more likely to have voted in the presidential election than Whites. The effect of race on voting was significant, but in the opposite direction. That is, Whites were more likely to vote in a presidential election, controlling for education, income, media use, and church involvement, b ¼ .026, p < .10. The interaction between race and church attendance was not a significant predictor of voting, b ¼ .008, p ¼ .565. Hypothesis 1 was not supported. Hypothesis 2 predicted that Blacks with high levels of church involvement would be more likely to have voted in a national election than Whites, controlling for church involvement. Church involvement was a measure of participation in church activities outside of attending sermons or mass. The results from this analysis mirror those of Hypothesis 1, such that Whites were more likely to vote, even when controlling for church involvement, income, 344 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah media use, and education, b ¼ .028, p < .05 (see Table 1) The interaction between race and church involvement was also not significant in predicting voting, b ¼ .005, p ¼ .585. Figure 1 visually depicts this relationship. Hypothesis 2 was not supported. The second set of hypotheses predicted that the interaction of race and church attendance (and involvement) would significantly predict individuals’ civic engagement. We expected these results because of prior research indicating that civic engagement tends to differ from voting, and Blacks tend to participate more actively in their communities than Whites. Hypothesis 3 predicted that Blacks with high levels of church attendance would demonstrate greater levels of civic engagement than Whites, controlling for church attendance. Race was not a significant predictor of civic engagement when examined alone, b ¼ .007, p ¼ .70. Yet, when examined alone controlling for other variables, church attendance significantly predicted civic engagement, b ¼ .117, p < .001. Importantly, when the interaction between church attendance and race was included, this produced a positive prediction of civic engagement, b ¼ .103, p < .001 (see Figure 2). Hypothesis 3 was supported. However, as we have suggested, church attendance is not the only way to measure involvement in religious cultural activities. Church involvement— measured by the involvement in church-related activities outside of attending service—might yield different results than the simple measure of frequency of attending service. Hypothesis 4 predicted that Blacks with high levels of church involvement would demonstrate more civic engagement than Whites TABLE 1 SES, Media Use, Race, and Church Involvement as Predictors of Voting. Predictor Model 1 Education Total household income Model 2 Education Total household income Days in past week read a daily newspaper Hours of TV watched on average weekday Hours spent using the Internet in typical week Model 3 Education Total household income Days in past week read a daily newspaper Hours of TV watched on average weekday Hours spent using the Internet in typical week Race (White ¼ 0, Black ¼ 1) Church involvement (no ¼ 0, yes ¼ 1) Race Church Involvement interaction F b 718.597 .208 .088 422.414 .196 .065 .165 .030 .017y 298.571 .187 .059 .161 .020 .013y .028 .103 .005 Notes. Adjusted R2 ¼ .065 for Model 1; Adjusted R2 ¼ .092 for Model 2; Adjusted R2 ¼ .103 for Model 3. p < .01. p < .001. y p < .05. Race and Social Capital FIGURE 1 The interaction of race and church involvement by voting. FIGURE 2 The interaction of race and church attendance by civic engagement. 345 346 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah TABLE 2 SES, Media Use, Race, and Church Involvement as Predictors of Civic Engagement. Predictor F b Model 1 Education Total household income Model 2 Education Total household income Days in past week read a daily newspaper Hours of TV watched on average weekday Hours spent using the Internet in typical week Model 3 Education Total household income Days in past week read a daily newspaper Hours of TV watched on average weekday Hours spent using the Internet in typical week Race (White ¼ 0, Black ¼ 1) Church involvement (no ¼ 0, yes ¼ 1) Race Church Involvement interaction 1290.660 .247 .141 643.339 .223 .112 .140 .051 .051 648.799 .206 .109 .136 .052 .057 .027 .211 .074 Notes. Adjusted R2 ¼ .107 for Model 1; Adjusted R2 ¼ .129 for Model 2; Adjusted R2 ¼ .193 for Model 3. p < .01. p < .001. with either high or low levels of church involvement. The results from this analysis are presented in Table 2. Regression coefficients are positive and significant for both race and church involvement, and the interaction between these two is also significant in predicting civic engagement. Figure 3 illustrates this interaction, showing that Blacks are more civically engaged the more they are involved in church activities outside of attendance. Figure 3. Hypothesis 4 was supported. DISCUSSION It was expected that political and civic participation would be greater for Blacks than for Whites based on their levels of church attendance and church involvement. The findings suggest that although greater levels of church attendance and involvement outside of church services do lead to more political participation for both racial groups, Whites overall displayed a stronger tendency to vote in the 1996 presidential election than Blacks. However, our findings suggest that regular church attendance (i.e., every week, more often than that, or almost every week) and involvement with church, such as in church committees and choir, significantly relate to more civic engagement among Blacks than Whites. The first area in which these results have important implications is for the study of social capital and communication. Although communication Race and Social Capital 347 FIGURE 3 The interaction of race and church involvement by civic engagement. scholars have examined religiosity and communication in the creation of social capital (Nisbet et al., 2003; Scheufele et al., 2003) their studies have for the most part been specific to individual religious beliefs, such as adherence to doctrinal conservativism. These studies also overlook the differences between Whites and Blacks (where Blacks are often grouped into one category of non-Whites), even though Blacks have been shown to attend church at different rates and participate differently (Putnam, 2000; Taylor, Chatters, Jayakody, & Levin, 1996). The present study sought to bring attention to this measurement issue within the communication research on social capital. This area is ripe for future research that examines the rich contextual and structural differences within church networks, where social capital is extremely likely to be formed (Putnam, 2000; Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, 1995). We see a need to not only examine the relations among members of churches, but also to draw attention to the different facets of social capital that can be obtained via racial and cultural means. The inclusion of such considerations, as demonstrated in the present study, could influence differences in political and civic participation. Furthermore, the literature shows that Black and White religiosity are in fact very different from each other, so to test the relationship between church attendance or religious networks without respect to race is to ignore an important element of those networks. Religion and community need to share a strong bond if religious involvement is to increase social capital. As 348 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah McConkey (2000) put it, ‘‘religious people are likely to generate increased social capital only when ‘religious capital’ is a widely shared community resource’’ (p. 86). Clearly, more research is needed to assess what makes the social capital gained in Black church networks different from those in White church networks. This study alerts communication and other scholars to differences among the ‘‘glue’’ within seemingly similar groups. This study also demonstrates that media use variables continue to influence citizens’ civic and political participation. These findings show reading the newspaper and time spent using the Internet were each positively linked to civic engagement and voting. Moreover, results from this study reveal a negative relationship between television viewing and both civic engagement and voting. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown newspaper reading is positively linked to civic and political participation (Keum et al., 2003; McLeod et al., 1999; Shah et al., 2001; Wilkins, 2000) whereas general television viewing has shown a significant but weaker negative association to civic and political participation (see Brehm & Rahn, 1997; Jeffries, Guowei, Neuendorf, & Bracken, 2004; Norris, 1996). It should be noted however, that general television and newspaper use measures are not ideal since they fail to examine different types of media forms and content which may produce different effects. For example, watching television entertainment has shown to have significantly negative effects on civic or political participation (see Keum et al., 2002; Norris, 1996; Scheufele, 2000), whereas viewing television news or political affairs shows can have some positive effects on participation (see Keum et al., 2003; Norris, 1996; Wilkins, 2000). Future research should include media variables that are content-specific and examine how specific media and content may affect Black and White respondents’ participation differently. For instance, research generally shows that viewing television is negatively associated with participation whereas newspaper reading is positively associated with participation. However, some researchers argue that Blacks may be an exception to this rule given their heavier use of and reliance on television as a source of information (Allen & Chaffee, 1980). In fact, in the CPS American National Election study, 75% of Blacks reported television as their most important source for campaign information (Latimer, 1983). Allen and Chaffee (1980) concluded that ‘‘politically active Blacks are distinguished by more specific and motivated uses of the news media than are others,’’ (p. 517) and that this principle extends to their use of television. There are those scholars who argue, however, that although Blacks do rely on television for political information, those Blacks who actually vote in elections are more likely to use both television and newspapers (Latimer, 1983) and seek out ethnic media to inform them on political issues that are pertinent to Black Americans (Jeffries, 2000) Future research should examine these relationships in terms of how they might vary depending on church attendance and involvement. Race and Social Capital 349 We see this study as an important step toward including race and culture as variables in studies of social capital. Not only can researchers use this information to further explore the religious participation differences by race and culture, they can assess finer-tuned communication variables within church networks. Beneficial contributions to the field would be interviews with church members of different denominations and possibly observation of the political communication that occur therein. Such hands-on research could provide greater insights into racial differences by acknowledging structural, cultural, and organizational components of church networks. A second major direction that research in this area can take is the examination of Black voter turnout at the local level. Although at first glance, these findings echo others that suggest Blacks are not as politically involved as their White counterparts (e.g., Musick et al., 2000), it has been suggested that Blacks demonstrate higher turnout rates in local elections (e.g., for mayoral, school board, and city council races) because there they have a greater sense of political efficacy (Calhoun-Brown, 1996; Gilliam & Kaufman, 1998; Marger, 2005). As such, Black churchgoers with greater political efficacy may be more politically active (Mangum, 2003; Wald, 1987). In addition, ‘‘symbolic politics’’ suggests that the presence of Black candidates stimulates Black voters to turn out at the polls. Gilliam and Kaufman (1998), for example, argued that Blacks become more engaged in the political process when they become more visible in political office, particularly at the local level. However, much of the empirical research on political participation has focused on voting in national elections rather than turnout during such local elections. Although this can serve as a baseline measure and ultimately lead to more generalizable findings, bringing the measure to the local political level might provide richer data about Black participation. The results from this study indicate, as expected, that Black respondents with high levels of church attendance and involvement demonstrated greater levels of civic engagement than Whites with high or low church attendance or involvement. As the data indicate, active Black churchgoers are intimately involved in their communities. The implications of this relationship are that frequent civic engagement could influence a perceived investment in the community, which in turn could lead Blacks to participate more in local elections. These findings suggest that future research should compare White and Black voter participation in local and national elections and include church involvement as a mediator in that relationship. Moreover, the influence of political efficacy on participation in both local and national elections, and the differences in efficacy between Blacks and Whites, should continue to be explored. Finally, future research should also examine the role that specific church denominations may play in stimulating political and civic involvement. For example, research suggests that conservative congregations are much less likely than liberal or moderate congregations to offer programs or services 350 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah to the community or address social and economic problems through political involvement (Greenberg, 2000). This is particularly relevant given that White conservative congregations like the evangelical church are the fastest growing churches (Greenberg, 2000). It is clear that these results suggest race doesplay a significant role in the distribution of political and civic participation in the United States, particularly when religiosity is taken into account. Both church attendance and participation in church-related activities are associated with civic engagement among Blacks at a higher rate than among Whites. A rich history of linked heritage and strong religiosity contribute, at least in part, to these differences found among Blacks and Whites. This finding is particularly relevant in an age where politicians are taking a market-segmentation approach to appeal to more voters (Bannon, 2004). This is evident among many campaign strategists who often develop and tailor campaign messages to voters using morality and religious imagery as a way to connect with citizens searching for issues that fit their religious values (see Scheufele et al., 2003). Given that people participate more when there are political issues that they feel strongly about in an election, the focus on political issues such as Voting Rights Act renewal, racial profiling, school vouchers, reparations, gay marriage, and stem cell research during certain national and local campaigns may increase Black churchgoers’ mobilization, providing scholars an even richer understanding of the role Black religiosity plays in civic and political participation. But perhaps more importantly, this study suggests that by acknowledging cultural differences between Blacks and Whites—specifically in terms of religious involvement—communication researchers can add a level of depth and understanding that is capable of parsing out unique cultural differences and is ultimately more inclusive. This study contributes to the communication research and theory in at least three ways. First, unlike previous research that has focused almost exclusively on either White (e.g., Brehm & Rhan, 1997; Scheufele & Shah, 2000; Shah et al., 2001) or Black (e.g., Brown et al., 2004; Brown & Wolford, 1994; Taylor & Thornton, 1993) respondents, this study compares civic and political participation between both Blacks and Whites. Second, this study suggests that the gap in Blacks’ and Whites’ political participation may not be as wide as some may suspect (e.g., Musick et al., 2000), particularly when considering individuals’ church involvement. Although Whites tend to be further ahead of Blacks in voting, when examining the influence of church involvement on civic engagement, Whites trail significantly behind their Black counterparts. Finally, this research contributes to our understanding of the role both traditional media (e.g., newspaper, television) and new media (e.g., Internet) play in influencing political and civic participation. The findings here suggest that, with the exception of television exposure, there is a positive link between individual’s media use (e.g., read newspaper, Internet use) and their Race and Social Capital 351 civic participation. This study should encourage communication researchers to explore more direct comparisons between Blacks and Whites and the role religiosity and media play in the political process. Further examination of racial and cultural differences in civic participation could help uncover the factors most likely to increase political participation and social capital in our society. Such research may reveal institutions and practices specific to certain cultural groups, like the Black church, that effectively stimulate civic and political participation among sub-groups and society at large. NOTES 1. Except for the West Oakland, California survey, which ran from December 2000 to February 2001. 2. Some sponsoring organizations requested oversampling. The Boston Foundation requested an oversample of 200 people in four zip codes; the Cleveland Foundation requested an oversample of 100 Latinos in Cuyahoga County, OH; the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation requested an oversample of 160 in Cheshire County and 40 in the I-93 corridor; and the Rochester County C.F. requested an oversample to achieve a minimum of 100 Blacks and 100 Latinos. REFERENCES Abrahmson, P. R. & Claggett, W. (1984). Race-related differences in self-reported and validated turnout. The Journal of Politics, 46, 719738. Allen, R. L. & Chaffee, S. H. (1980). Mass communication and the political participation of black Americans. Communication Yearbook, 3, 507522. Ball-Rokeach, S. J., Kim, Y., & Matei, S. (2001). Storytelling neighborhood: Paths to belonging in diverse urban environments. Communication Research, 28, 392428. Bannon, D. P. (2004, November). Marketing segmentation and political marketing. Paper presented at the annual conference for Contemporary Political Studies, Lincoln University, England. Barnes, S. L. (2003). Determinants of individual neighborhood ties and social resources in poor urban neighborhoods. Sociological Spectrum, 23, 463497. Brehm, J. & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41, 9991023. Bridges, F. W. (2001). Resurrection song: African-American spirituality. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. Brown, R. K. & Brown, R. E. (2003). Faith and works: Church-based social capital resources and African American political activism. Social Forces, 82, 617641. Brown, R. K., McKenzie, B. D., & Taylor, R. J. (2003, Winter). A multiple sample comparison of church involvement and Black political participation in 1980 and 1994. African American Research Perspectives, 9, 117132. Brown, R. & Wolford, M. L. (1994). Religious resources and African American political action. The National Political Science Review, 4, 3048. 352 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah Calhoun-Brown, A. (1996). African American churches and political mobilization: The psychological impact of organizational resources. Journal of Politics, 58, 935953. Cavanagh, T. E. (1991). When turnout matters: Mobilization and conversion as determinants of election outcomes. In W. Crotty (Ed.), Political participation and American democracy (pp. 89112). New York: Greenwood. Chaves, M. & Higgins, L. M. (1992). Comparing the community involvement of Black and White congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31, 425440. Cohen, J. E., Cotter, P. R., & Coulter, P. B. (1983). The changing structure of southern political participation: Matthews and Prothro 20 years later. Social Science Quarterly, 64, 536549. Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94S, S95S120. Federico, C. M. & Luks, S. (2005). The political psychology of race. Political Psychology, 26, 661666. Gilliam, F. D. & Kaufman, K. M. (1998). Is there an empowerment life cycle? Long-term black empowerment and its influence on voter participation. Urban Affairs Review, 33, 741766. Green, M. C. & Brock, T. C. (1998). Trust, mood, and outcomes of friendship determine preferences for real versus ersatz social capital. Political Psychology, 19, 527544. Greenberg, A. (2000). The church and the revitalization of politics and community. Political Science Quarterly, 115, 377393. Harris, F. C. (1999). Something within: Religion in African-American political activism. New York: Oxford University Press. Hirsch, B. J., Mickus, M., & Boerger, R. (2002). Ties to influential adults among black and white adolescents: Culture, social class, and family networks. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 289303. Jeffries, L. W. (2000). The impact of ethnicity and ethnic media on presidential voting patterns. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 199, 197262. Jeffries, L. W., Guowei, J., Neuendorf, K., & Bracken, C. (2004, November). Social capital: community engagement vs. political participation. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Midwest Association of Public Opinion Research, Chicago. Johnson, C. L. (1995). Adaptation of very old Blacks. Journal of Aging Studies, 9, 231244. Kanervo, E., Zhang, W., & Sawyer, C. (2005). Communication and democratic participation: A critical review and synthesis. The Review of Communication, 5, 193236. Keum, H., Cho, J., Rojas, H., Shah, D. V., McLeod, D. M., & Pan, Z. (2003, November). Rethinking the virtuous circle: Reciprocal relationships between communication and civic engagement. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Association for Public Opinion Research, Chicago. Krysan, M. (2002). Community undesirability in Black and White: Examining racial residential preferences through community perceptions. Social Problems, 49, 521543. Race and Social Capital 353 Latimer, M. K. (1983). The newspaper: How significant for Black voters in presidential elections? Journalism Quarterly, 60, 1623. Leighley, J. E. & Vedlitz, A. (1999). Race, ethnicity, and political participation: Competing, models, and contrasting explanations. The Journal of Politics, 61, 10921114. Lincoln, C. E. & Mamiya, L. (1990). The Black church in the African American experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Macaluso, T. F. & Wanat, J. (1979). Voting turnout and religiosity. Polity, 12, 158169. Mangum, M. (2003). Psychological involvement and black voter turnout. Political Research Quarterly, 56(1), 4148. Marger, M. (2005). Race and ethnic relations: American and global perspectives. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth=Thomson Learning. Martinson, O. B. & Wilkening, E. A. (1987). Religious participation and involvement in local politics throughout the life cycle. Sociological Forces, 20, 309318. McCarthy, J. & Castelli, J. (1998). Religion-sponsored social service providers: The non-so-independent sector. Working Paper Series. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute. McConkey, D. (2000). Religion, social capital, and the significance of community. In D. McConkey & P. A. Lawler (Eds.), Social structures, social capital, and personal freedom (pp. 8397). Westport, CT: Praeger. McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., & Moy, P. (1999). Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Political Communication, 16, 315336. Musick, M. A., Wilson, J., & Bynum, W. B. (2000). Race and formal volunteering: The differential effects of class and religion. Social Forces, 78, 15391571. Nisbet, M. C., Moy, P., & Scheufele, D. A. (2003, May). Religion, communication, and social capital. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, San Diego, CA. Norris, P. (1996). Does television erode social capital? A reply to Putnam. PS: Political Science & Politics, 29, 474477. Oliver, M. (1998). The urban Black community as network: Toward a social network perspective. The Sociological Quarterly, 29, 623645. Pattillo-McCoy, M. (1998). Church culture as a strategy of action in the Black community. American Sociological Review, 63, 767784. Pinn, A. P. (2002). The Black church in the post-Civil Rights era. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis. Putnam, R. D. (1995). Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Political Science & Politics, 27, 664683. Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Touchstone. Saguaro Seminar. (2001). Social capital community benchmark study: Executive summary. Retrieved August 3, 2007, from http://www.cfsv.org/communitysurvey/ docs/exec_summ.pdf Scheufele, D. A. & Nisbet, M. C. (2003). Being a citizen online: New opportunities and dead ends. Harvard International Journal of Press-Politics, 7, 5575. 354 L. H. Hoffman and O. Appiah Scheufele, D. A., Nisbet, M. C., & Brossard, D. (2003). Pathways to participation? Religion, communication contexts, and mass media. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 15, 300324. Scheufele, D. A. & Shah, D. V. (2000). Personality strength and social capital: The role of dispositional and informational variables in the production of civic participation. Communication Research, 27, 107131. Schudson, M. (1999). The good citizen: A history of American civic life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Shah, D. V. (1998). Civic engagement, interpersonal trust, and television use: An individual-level assessment of soc’ial capital. Political Psychology, 19, 469496. Shah, D. V., McLeod, J. M., & Yoon, S. (2001). Communication, context, and community: An exploration of print, broadcast, and Internet influences. Communication Research, 28, 464506. Sherkat, D. E. & Ellison, C. G. (1991). The politics of Black religious change: Disaffiliation from black mainline denominations. Social Forces, 70, 431454. Shimkin, D. B., Shimkin, E. M., & Frate, D. A. (Eds.). (1978). The extended family in Black societies. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton Publishers. Silverman, R. M. (2001). CDCs and charitable organization in the urban south: Mobilizing social capital based on race and religion for neighborhood revitalization. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 30, 240268. Social Capital Community Benchmark Survey. (2001). Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Benchmark Survey. Retrieved August 3, 2007, from http://www. cfsv.org/communitysurvey/faqs.html Southwell, P. L. & Pirch, K. D. (2003). Political cynicism and the mobilization of Black voters. Social Science Quarterly, 84, 906917. Strate, J. M. et al. (1989). Life span civic development and voting participation. The American Political Science Review, 83, 443464. Tate, K. & Brown, R. (1991, April). Black political participation revisited. Paper presented at the meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL. Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Jayakody, R., & Levin, J. S. (1996). Black and White differences in religious participation: A multisample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35, 403410. Taylor, R. J., Thornton, M. C., & Chatters, L. M. (1988). Black Americans’ perceptions of sociohistorical role of the church. Journal of Black Studies, 18, 123138. Uslaner, E. M. (1998). Social capital, television, and the ‘‘mean world’’: Trust, optimism, and civic participation. Political Psychology, 19, 441467. Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Wald, K. (1987). Religion and politics in the United States. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Wilkins, K. G. (2000). The role of media in public disengagement from political life. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 44, 569. Wood, G. S. Jr. & Judikis, J. C. (2002). Conversations on community theory. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.