This article was downloaded by: [Hoffman, Lindsay] On: 28 April 2009

advertisement

![This article was downloaded by: [Hoffman, Lindsay] On: 28 April 2009](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010502256_1-5117f3f76ce55d37394710dba49bfdda-768x994.png)

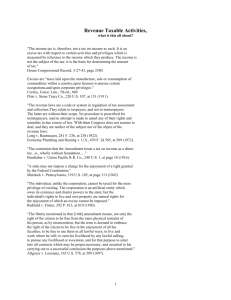

This article was downloaded by: [Hoffman, Lindsay] On: 28 April 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 910776093] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Communication Research Reports Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t714579429 Explaining the Gap: The Interaction of Gender and News Enjoyment in Predicting Political Knowledge Jillian Nash; Lindsay H. Hoffman Online Publication Date: 01 April 2009 To cite this Article Nash, Jillian and Hoffman, Lindsay H.(2009)'Explaining the Gap: The Interaction of Gender and News Enjoyment in Predicting Political Knowledge',Communication Research Reports,26:2,114 — 122 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/08824090902861556 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08824090902861556 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Communication Research Reports Vol. 26, No. 2, May 2009, pp. 114–122 Explaining the Gap: The Interaction of Gender and News Enjoyment in Predicting Political Knowledge Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 Jillian Nash & Lindsay H. Hoffman This study investigated emotion as a potential explanation for the omnipresent gender gap in political knowledge. Past studies have examined methodological issues, socioeconomic attributes, and media use as possible contributors, but have not included enjoyment of media use as a factor in the relation between gender and political knowledge. Using 2007 data from the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, it was found that, in line with uses and gratifications theory, enjoyment did indeed play a role in the acquisition of political information, and increased enjoyment resulted in higher political knowledge. This relation was stronger for women than for men. Keywords: Emotion; Media Use; Political Knowledge; Women The presence of a public-affairs knowledge gap in the United States has been a subject of concern and study for years. A series of nationwide surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press (2000, 2007) have found that women continually score lower than men on knowledge of basic facts pertaining to current events. Considering the strides women have made in the last few decades in terms of educational and congressional representation, these repeated findings continue to be both surprising and alarming. Theoretically speaking, knowledge gaps should not exist in a nation that promotes equal opportunity for all of its citizens. A flaw in our allegedly fair system deserves attention and, further, necessitates repair. Of Jillian Nash (BA, College of New Jersey, 2007) is a master’s student in Communication at the University of Delaware. Lindsay Hoffman (PhD, Ohio State University, 2007) is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Delaware. Correspondence: Lindsay H. Hoffman, Department of Communication, University of Delaware, 250 Pearson Hall, 125 Academy St., Newark, DE 19716; E-mail: lindsayh@udel.edu ISSN 0882-4096 (print)/ISSN 1746-4099 (online) # 2009 Eastern Communication Association DOI: 10.1080/08824090902861556 Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 Communication Research Reports 115 course, the first step is to determine the plausible causes of this disparity. Some research has tested for the existence of the gap (Kenski & Jamieson, 2000), but few studies have sought to actually explain why it exists. The current project examines this very important question. The few studies that have investigated the reason behind the public affairs knowledge gap have identified faulty methodology as a possible contributor. For instance, McGlone, Aronson, and Kobrynowicz (2006) argued that the slanted results are a product of survey stereotype. In other words, questions on measurement tools tend to be biased toward men. After conducting an experiment, the researchers found that the difference in scores on a political knowledge test was reliably moderated by two factors: bias of the question set and gender of the interviewer. Research has also demonstrated that women are more likely to give ‘‘do not know’’ responses to questions assessing political knowledge, and men are more likely to guess the answers on questions they do not know (Kenski, 2000). This suggests that the scoring of political knowledge questionnaires might be slightly skewed in favor of men because they are more likely to give the correct response, perhaps by chance, even if they did not actually know the answer to a question (see Mondak & Canache, 2004). Because this gender gap has persisted over time, there is a good chance that faulty methodology is not the only explanation. In fact, a study conducted in 2004 found that a variety of variables including socioeconomic and demographic factors, political attitudes, political engagement, media exposure, and political life circumstances result in a moderate reduction in the magnitude of gender as a predictor of political knowledge (Garand, Guynan, & Fournet, 2004). The finding of media use as a factor in the relation between gender and political knowledge provides an interesting point for discussion. Past studies on the usage of new media have indicated the existence of a gender gap. In accordance with Garand et al., this media use gap could potentially help to explain the political knowledge gap. If women are not using new media as much as men, they are probably not acquiring as much political information as men. It is interesting to note that a recent study found this gap is closing in the United States (Ramen, Broege, Davis, & Steinmetz, 2006). Therefore, media exposure may be becoming less and less of a factor. Even if media use does not play a large role as a moderator in the gender–political knowledge relation, the media cannot and should not be ignored—they are the principle source for the acquisition of public knowledge. McQuail (2005) argued: People do learn from the news and become more informed as a result. The extent to which news has effects depends on its reaching an audience that pays some attention to the content, understands it, and is able to recall or recognize some of it after the event. (p. 504) Thus, the audience’s actual relation with media usage is one that warrants further exploration. It is important to note that men and women typically prefer different types of news messages and content. Mood, a possible prerequisite for an enjoyable Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 116 J. Nash & L. H. Hoffman experience, may play a role in the absorption of political information. After a moodimpacting experience, men tend to distract themselves with absorbing messages, whereas women tend to ruminate about the experience and thus prefer messages with lower absorption potential (Knobloch-Westerwick, 2007). This may help to explain why men retain more political information than women do, especially when a mood-impacting current event or issue perpetuates media exposure. An example might illustrate a possible scenario where mood could influence information acquisition and subsequent knowledge. Imagine an audience viewing a breaking news report about a devastating attack in the Iraq War. Simply watching this news report could put the viewers in a negative mood. Men might then seek to distract themselves with absorbing messages pertaining to the latest news in the 2008 U.S. presidential race, thus increasing the potential to gain political knowledge. Women, on the other hand, may continue to dwell on the negative news and miss out on absorbing the important political information. Emotions might also play a role in information comprehension and retention; in some cases, emotion might have greater effects on comprehension than cognitions (Bennett, 2007). Indeed, compared to men, women report more enjoyment from, and form more favorable judgments of, positively framed versions of news stories, whereas men tend to report more favorable judgments of negatively framed versions of those same stories (Kamhawi & Grabe, 2007). Kamhawi and Grabe also found that women’s favorable views toward positive messages—as well as their unfavorable views toward negative messages—are stronger than men’s. News reports typically contain more ‘‘bad news’’ than ‘‘good news’’ (Carroll, 1985; Farnsworth & Lichter, 2007; Lichter & Noyes, 1996; Shoemaker, 1996), and recognition and comprehension of negatively framed messages is greater for men than it is for women (Grabe & Kamhawi, 2006). Thus, the increased comprehension of news among men could explain why surveys find lower political knowledge among women. The relation between gender and political knowledge, from the perspective of news media use, becomes easier to understand when considering the uses and gratifications approach of mass communication studies (Blumler & Katz, 1974). The approach is based on the ancient Greek philosophy of hedonism, which is the belief that humans naturally seek out sources of pleasure. It states that ‘‘media use depends on the perceived satisfactions, needs, wishes, or motives of the prospective audience member’’ (McQuail, 2005, p. 423). Therefore, the actions that humans take, including whether they use media or whether they gain political knowledge, are dependent on whether they actually enjoy the processes. Nabi and Krcmar (2004) conceptualized media enjoyment as ‘‘a three-dimensional construct comprised of affective, cognitive, and behavioral information that mutually exert influence on one another’’ (p. 296). They argued that enjoyment is an attitude and, therefore, encompasses these intrinsic components. Clearly, the behavioral component becomes a major player in this relation when considering media use from a uses and gratifications perspective. Past research, however, has not always examined the role of enjoyment in seeking gratification. In fact, Nabi and Krcmar argued that ‘‘it is treated as an inferred cognitive outcome rather than a multifaceted component Communication Research Reports 117 Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 of the dynamic process of gratification seeking’’ (p. 301). This article considers the often overlooked role of enjoyment as a predictor, rather than an outcome. Media enjoyment might very well be a determining factor in the acquisition of political knowledge through media use. Taken together, various lines of research suggest the need to study the relationships among gender, political knowledge, enjoyment, and media use. Several hypotheses emerge. First, it is reasonable to expect an association between the amount of media people use and how much they enjoy keeping up with the news. More specifically, due to natural hedonistic tendencies, people’s enjoyment should predict how much media they use. Thus, we hypothesized the following: H1: There will be a correlation between level of enjoyment of keeping up with the news and media use. H2: Level of enjoyment of keeping up with the news will be a significant predictor of amount of media use. In addition, it is possible that a relation exists between how much people enjoy keeping up with the news and their level of political knowledge. As suggested earlier, there is reason to believe that enjoyment is a predictor of political knowledge. To examine this possibility, we predicted the following: H3: There will be a correlation between level of enjoyment of keeping up with the news and political knowledge. H4: Level of enjoyment of keeping up with the news will be a significant predictor of level of political knowledge. Last, it is important to ascertain whether enjoyment of keeping up with the news helps explain the existence of the political knowledge gap. Lack of enjoyment or pleasure could be a reason why women are not retaining information from news sources. Accordingly, we expected that H5: Gender will act as a moderator in the relation between enjoyment of keeping up with the news and political knowledge. Method This study was a secondary analysis of recent political knowledge survey data from The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press (2007). This nationwide telephone poll was conducted in February 2007 through random digit dialing. Participants (N ¼ 1,502) ranged in age from 18 to 95 years old (M ¼ 46.9, SD ¼ 19.0), and 50.9% of the sample consisted of women. Participants’ annual family income ranged from less than $10,000 to $150,000 or more (M ¼ 5.7) or between $40,000 and $75,000 (SD ¼ 2.8). Education level varied from a few years of grade school to post-graduate studies (M ¼ 4.3; or some school after high school, SD ¼ 1.7). Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 118 J. Nash & L. H. Hoffman Enjoyment was measured by the item, ‘‘How much do you enjoy keeping up with the news?’’ Responses ranged from 1 (not at all), 2 (not much), 3 (some), to 4 (a lot) to fall in line with the hypotheses (M ¼ 3.2, SD ¼ 0.9). Additive scales were created to operationalize both political knowledge and media use. The Pew Research Center combined 23 items to create a political knowledge index. Each correct answer counted as one point, producing a scale that ranges from 0 (no correct answers) to 23 (a perfect score). The items included questions about identifying U.S. and world leaders, knowledge about current U.S. political legislation, knowledge about the Iraq war, and knowledge about the candidates running in the 2008 U.S. presidential election (M ¼ 12.9, SD ¼ 5.3; for question wording, see The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2007). The media use scale was created by combining 16 different items, including whether participants watched the national nightly network news on CBS, ABC or NBC; watched Cable News Network (CNN); watched the Fox News (cable) Channel; watched the local news about their viewing area; watched NewsHour With Jim Leher; watched The Today Show, Good Morning America, or The Early Show; watched The O’Reilly Factor with Bill O’Reilly; watched shows like The Colbert Report or The Daily Show with Jon Stewart; listened to National Public Radio; listened to Rush Limbaugh’s radio show; read news magazines such as Time, U.S. News, or Newsweek; read a daily newspaper; read Internet 1 news Web sites, such as GoogleTM News or Yahoo! News; read network TV news Web sites such as CNN.com or MSNBC.com; read the Web sites of major national newspapers such as USA Today.com, New York Times.com, or the Wall Street Journal online; or read online blogs where people discuss events in the news (M ¼ 4.63, SD ¼ 2.84). Results In testing H1, we found, as expected, a significant correlation between the enjoyment of keeping up with the news and one’s media use (Spearman’s r ¼ .449, p < .001). As predicted in H3, there was a significant correlation between the enjoyment of keeping up with the news and political knowledge (Spearman’s r ¼ .554, p < .001). These served as the initial tests for the relations between the key variables under study, and revealed significant associations between enjoyment of keeping up with news and both media use and political knowledge. H2 and H4 predicted that enjoyment of keeping up with the news would be a significant predictor of amount of media use and level of political knowledge. Two regression analyses, controlling for level of education, gender, and income, were run to test these hypotheses. As expected, enjoyment of keeping up with the news was a positive and significant predictor of amount of media use, even after controlling for gender, education, and income (b ¼ 1.15, SE ¼ .07, p < .01). Enjoyment of keeping up with the news was also a positive and significant predictor of political knowledge (b ¼ 1.97, SE ¼ .15, p < .01). H2 and H4 were supported. Table 1 summarizes these results. H5 predicted an interaction effect in which gender moderates the association between enjoyment of keeping up with the news and political knowledge. After running a multiple regression, we found support for H5. A significant interaction was Communication Research Reports 119 Table 1 Regression Analyses Predicting Media Use and Political Knowledge Media usea b Variable Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 First block Education Income Second block Education Income Gender Enjoyment of keeping up with news Gender Enjoyment Political knowledgeb SE b SE 0.137 0.078 .050 .035 1.127 0.565 .082 .057 0.038 0.041 0.116 1.150 — .049 .034 .143 .074 — 0.907 0.378 0.626 1.968 0.527 .073 .051 .698 .149 .214 Note. Beta coefficients are unstandardized. a Adjusted R2 ¼ .160, F change ¼ 123.078 . bAdjusted R2 ¼ .456, F change ¼ 176.735 . p < .05. p < .01. observed between enjoyment of keeping up with the news and gender in predicting political knowledge (b ¼ 0.53, SE ¼ .21, p < .05). As Figure 1 illustrates, men appear to gain more political knowledge from their enjoyment of news than do women. Figure 1 Interaction Between Gender and Enjoyment of Keeping Up with the News on Political Knowledge. 120 J. Nash & L. H. Hoffman Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 Discussion This study sought to examine the relations among media use, enjoyment of keeping up with the news, political knowledge, and gender using the uses and gratifications approach as a theoretical framework. In line with H1 and H2, we found that a person’s level of enjoyment of keeping up with the news is significantly associated with—and predicts—media use. We also observed a significant relation between enjoyment and political knowledge. More specifically, enjoyment acted as a predictor for level of political knowledge. Thus, H3 and H4 were also confirmed. These findings support the idea of hedonism as an important aspect of the uses and gratifications approach. It appears that people use the news media and retain political information when they enjoy keeping up with the news, perhaps because they are innately pleasure-seekers. Because women do not appear to enjoy keeping up with the news as much as men do, practitioners and scholars alike should examine how to make viewing news a more enjoyable experience for women. This does not necessarily mean that news media will have to soften their content; important news is important news, and must be reported to the public regardless of the emotion it evokes. Rather, news outlets may want to focus on taking women’s concerns into account to deliver news in a more enjoyable manner. Future research should seek to determine how to format and cover stories in a different way, by determining both what news is of most interest to women and how stories can be rewritten in a way that is more appealing to women. By doing so, media outlets will not only attract larger audiences, they will also potentially aid in closing the political knowledge gap. The main purpose of this study was to determine whether gender plays a role in the relationship between enjoyment of keeping up with the news and political knowledge. This notion was supported through the testing of H5. We found that men, who have higher levels of political knowledge, tend to enjoy keeping up with the news more than women, who typically have lower levels of political knowledge. This finding is extremely important for its implications; it may indicate that women are not retaining political information because they are not enjoying the sources from which they obtain it. These results add credence to the experimental findings of Grabe and Kamhawi (2006), who concluded that women experience avoidance responses to negative messages, rating positive stories as more arousing, and processing such messages more effectively than negative ones. Positive emotional responses to news, such as enjoyment, can aid in women’s comprehension of news, as well as their subsequent comprehension of the information therein. As Figure 1 demonstrates, increased enjoyment results in higher political knowledge, but this relationship is stronger for men than for women—that is, men potentially get more out of watching the news when they enjoy it than women do. Like any research study, this one has its limitations. First, we assumed that ‘‘enjoyment of keeping up with the news’’ is synonymous for ‘‘enjoyment of the news.’’ It is possible for one to enjoy the content of news while not enjoying the process of keeping up with it. Future studies should operationalize these concepts Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 Communication Research Reports 121 as two separate variables so that differences between enjoyment of use and enjoyment of content can be tested against gender. Second, the knowledge gap may have begun to close in recent years. As Ramen et al. (2006) noted, women are now using new media as much as men are. This could impact the amount of political information they are accessing and attaining. Moreover, there have been recent changes in the political climate. For the first time in history, a woman, Hillary Clinton, was a viable contender for the U.S. presidency during the time of the Pew survey’s administration. News coverage of her campaign flooded media outlets for months. This news content may have sparked the attention of many women, as they may have found it easier to relate to news about a prominent female politician as opposed to news about the traditionally male-centered world of U.S. politics. Researchers should study enjoyment of media use during and after this monumental period of time to gauge potential changing trends. Despite these limitations, there are important practical and theoretical implications of our results. These findings support those of Nabi and Krcmar (2004), who conjectured that the nature of media enjoyment is more complex than previously thought. Enjoyment is not necessarily the byproduct of media use, but rather is an active predictor of its occurrence. This adds new insight to the uses and gratifications perspective, which has often considered enjoyment a reflexive outcome of the process. Our findings also indicate the importance of studying media enjoyment in relation to political knowledge, for there is an apparent connection between the two. Scholars often lament American citizens’ political apathy evidenced by poor voter turnout. Yet, undoubtedly, a large number of eligible voters abstain from voting because they do not feel informed enough on the issues to make a decision. This research can also contribute to the study of political knowledge and gender. Although many would say that men and women have finally achieved political equilibrium, the ever-present knowledge gap in this area demonstrates that inequity does indeed still exist. In light of this study’s findings, future research should consider media enjoyment as an impetus for political knowledge gain. This emotional component of news media use may be vital to ultimately leveling the playing field. References Bennett, W. L. (2007). News: The politics of illusion (7th ed.). New York: Pearson Longman. Blumler, J. G., & Katz, E. (1974). The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Carroll, R. (1985). Content values in TV news programs in small and large markets. Journalism Quarterly, 62, 877–938. Farnsworth, S. J., & Lichter, S. R. (2007). The nightly news nightmare: Television’s coverage of U. S. presidential elections, 1988–2004. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Garand, J., Guynan, E., & Fournet, M. (2004, January). The gender gap and political knowledge: Men and women in national and state politics. Paper presented at the Southern Political Science Association annual meeting, New Orleans, LA. Grabe, M. E., & Kamhawi, R. (2006). Hard wired for negative news? Gender differences in processing broadcast news. Communication Research, 33, 346–369. Downloaded By: [Hoffman, Lindsay] At: 18:46 28 April 2009 122 J. Nash & L. H. Hoffman Kamhawi, R., & Grabe, M. E. (2007, May). Why women are not watching: Gender differences in responding to negative, positive, and valence-ambiguous TV news. Paper presented at the International Communication Association annual conference, San Francisco, CA. Kenski, K. (2000). Women and political knowledge during the 2000 primaries. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 572, 26–28. Kenski, K., & Jamieson, K. H. (2000). The gender gap in political knowledge: Are women less knowledgeable than men about politics? In K. H. Jamieson (Ed.), Everything you think you know about politics . . . and why you’re wrong (pp. 83–92). New York: Basic Books. Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2007). Gender differences in selective media use for mood management and mood adjustment. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 51, 73–92. Lichter, S., & Noyes, R. (1996). Good intentions make bad news: Why Americans hate campaign journalism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. McGlone, M. S., Aronson, J., & Kobrynowicz, D. (2006). Stereotype threat and the gender gap in political knowledge. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 392–398. McQuail, D. (2005). Mass communication theory: An introduction (5th ed.). London: Sage. Mondak, J. J., & Canache, D. (2004). Knowledge variables in cross-national social inquiry. Social Science Quarterly, 85, 539–559. Nabi, R., & Krcmar, M. (2004). Conceptualizing media enjoyment as attitude: Implications for mass media effects research. Communication Theory, 14, 288–310. The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (2000). The public affairs gender gap. Retrieved May 11, 2008, from http://peoplepress.org/commentary/display.php3?AnalysisID=10 The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (2007). Public knowledge of current affairs little changed by news and information revolutions: February 2007 political knowledge survey. Retrieved March 3, 2008, from http://people-press.org/dataarchive/ Ramen, V., Broege, S., Davis, D., & Steinmetz, R. (2006, July). Gender differences in new media use: New Zealand, Germany, and the US. Paper presented at the International Communication Association annual conference, Dresden, Germany. Shoemaker, P. (1996). Hard wired for news: Using biological and cultural evolution to explain the surveillance function. Journal of Communication, 46, 32–47.