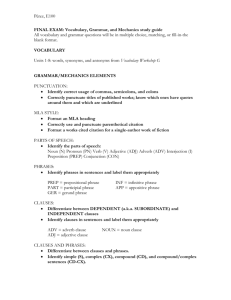

PUNCTUATION AND SYNTAX

advertisement