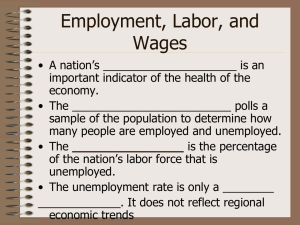

AS A WAGES Bachelor of Science New York University

advertisement