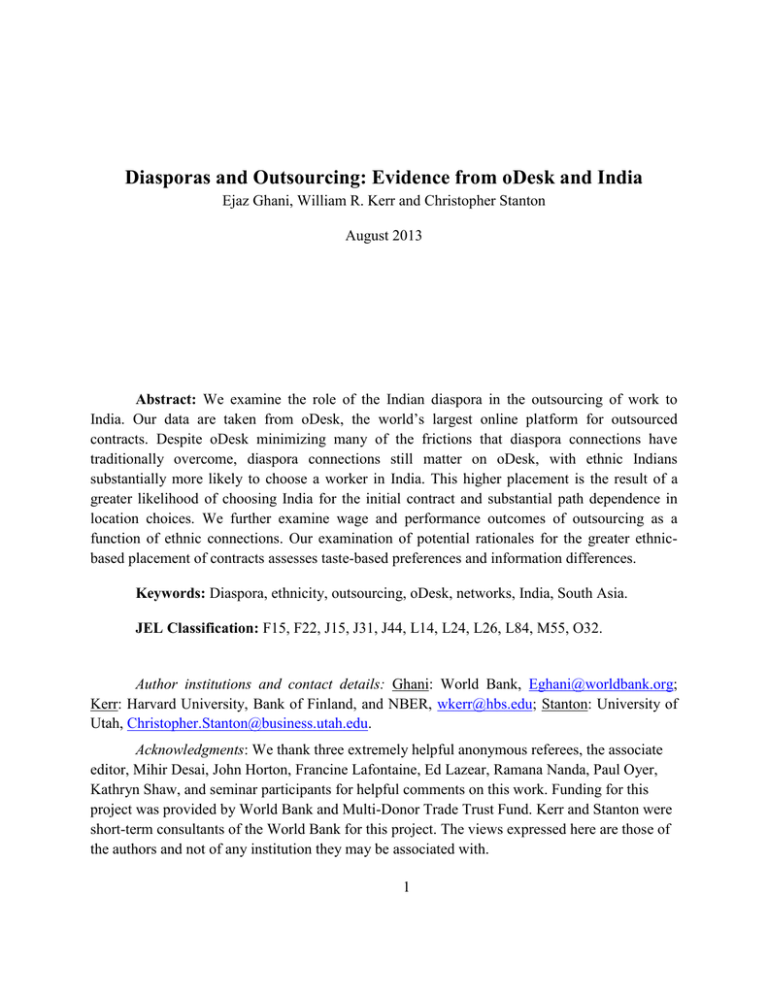

Diasporas and Outsourcing: Evidence from oDesk and India

advertisement