Document 10476193

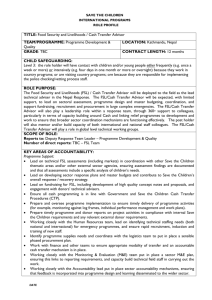

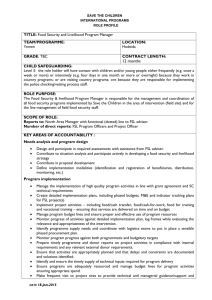

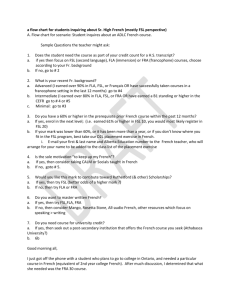

advertisement