Promoting Social-emotional Wellbeing in Early Intervention Services A Fifty-state View

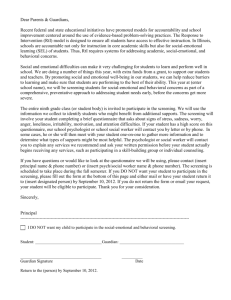

advertisement