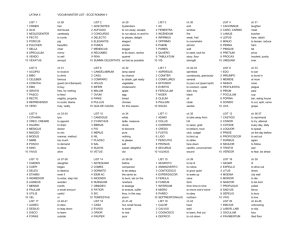

Latinas/os at the University of Illinois: 1992-2002

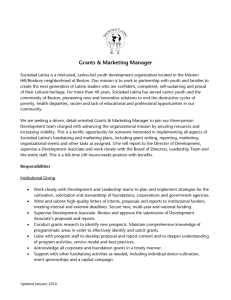

advertisement